Who’s afraid of Chinese Tones?

For people that haven’t studied the language, rumors of the four Chinese tones are passed around like ghost stories at a campfire. “If you say one word wrong nobody will understand!” “I heard the words for ‘horse’ and “mom” are almost the same!”

Are these real concerns, or are they perhaps overblown rumors? In this article, I’ll try to shine some light on Chinese tones.

What does it mean to be a tonal language?

In a tonal language, the relative pitch of a word carries lexical or grammatical meaning. There are languages like English and Indonesian, where pitch can indicate a sentence-level function like marking a question. There are languages like Swedish and Japanese, where certain syllables in words and sentences have to carry high or low pitch. And there are languages like Mandarin or Zapotec where each syllable carries a rising or falling pitch contour that can distinguish meaning or part of speech. These are the tonal languages..

Middle Chinese, spoken more than a thousand years ago, also had four tones – but they were vastly different from those of modern Mandarin. As Middle Chinese developed into today’s topolects like Cantonese and Shanghainese, the tones morphed and split and merged in unpredictable ways. Some topolects today have more than six tones, while some have just a simple high/low pitch distinction.

Let’s take a look at some examples. Mandarin today has four contour tones plus one neutral tone. It doesn’t get counted as part of the four since it only appears as the second syllable in some words – that is, it can’t stand on its own. In Taiwan and Southern China you hear the neutral tone in Mandarin a lot less.

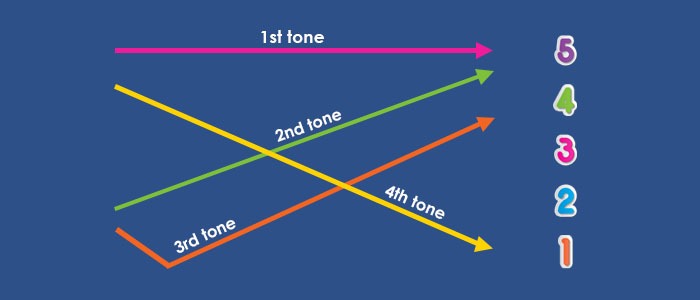

The four tones are numbered, and in pinyin they have diacritics which approximate the contour. The first tone is high and level: mā

The second is a rising pitch from medium to high: má

The third is a low tone that falls and rises. It’s a little more complicated, so I’ll expand on this soon: mǎ

The fourth tone starts high and quickly falls: mà

So that’s the ideal. That’s how the tones sound in pronunciation dictionaries, or when someone carefully speaks one syllable at a time.

How do the tones work in real life?

In this section, I’ll stick to Mandarin, or this article will be much longer. Let me tell you, though, tone is one of the most fascinating things I’ve ever studied and there are amazing things that happen in some languages. But for now:

The first thing to mention is the tone sandhi. Sandhi is Sanskrit for “change” and that’s a fine translation – tones change based on their environment. There are more in-depth articles on tone sandhi that you can take a look at in the future, but I’ll cover two big rules here for you now.

First, the word 不 (not) is pronounced with a fourth tone, right? Mostly, yes. But when it’s in front of another fourth-tone word, it changes to second tone. 不要 (don’t want) 不对 (incorrect) are two of the most common combinations for this type of sandhi.

Second, and perhaps the most important, when you have two third tones next to each other, the first of them turns to a second tone. How about that all-purpose greeting everybody learns on their first day of class? 你好! Listen to native speakers and you’ll hear the sandhi clear as day. But what happens with three third-tone words in a row, or more? I’ve doctored the pinyin here so it matches what native speakers say:

请给我 qǐnggéiwǒ Please give it to me.

你也想走吗? Níyěxiángzǒuma? Do you want to go too?

It alternates!

There’s another thing to mention about the third tone. In fast, connected speech, it doesn’t do the dipping fall-and-rise pattern that it does when pronounced alone. Instead, it simply takes a low, practically level tone. So when you say longer multi-syllable words and phrases, don’t stress about saying the full contour of the third tone. It only really comes out at the end of a phrase or when you’re really emphasizing the syllable.

Something that’s almost never touched on in learning material is the presence of stress in Mandarin. This is cutting-edge stuff and there’s not a lot of research out at the moment, so I’ll keep this section short. But the main idea is that some words with identical tones are nevertheless pronounced differently because of stress patterns. Let’s take the words 一生 (lifelong), 医生 (doctor), and 一声 (first tone) – all of these are pronounced yīshēng, yet native speakers actually pronounce them all slightly differently! Try out the nonsense sentence “医生一生没有说一声”(the doctor never said the first tone their whole life) on friends and tutors.

How can you pronounce the Chinese tones in a natural-sounding way?

Start by developing your ear for the tones in isolation. This is the number one thing you can do to lay a solid groundwork for Mandarin pronunciation in the future. A great place to start is this lesson on the Chinese Tones on LingQ. Listen to the audio to fine tune your ear.

If you never develop a good mental sense of the tones, you’ll constantly be running into misunderstandings. Next, you want to get a feel for tones in pairs and triplets. Just like 你好, there are hundreds of things native speakers say all the time that take the form of two or three syllable words. Names of famous people and places are perfect for this, since they’re usually at least three characters long. This can really have a huge impact on your pronunciation as you smoothly flow from one tone to the next.

Here’s a few examples to give you an idea what I mean:

华盛顿 – huáshèngdùn – Washington

津巴布韦 – jīnbābùwéi – Zimbabwe

印度尼西亚- yìndùníxīyà – Indonesia

圣彼得堡 – shèngbǐdébǎo – St. Petersburg

加拿大 – jiānádà – Canada

Then, of course, you move on to longer phrases and sentences. I love taking short segments of speech and trying to follow along as close as I can to the contours of the native recording. The more you actually get speaking after a native model, the more comfortable you’ll be – and you’ll be a natural at Chinese tones in no time.

Check out LingQ to discover how to learn Chinese from content you love!

Alex Thomas started seriously studying languages five years ago and will never stop. He has traveled to many of China’s cities, big and small, and cannot wait to return.