How To Read Chinese: 5 Steps

If you’ve ever looked at a block of Chinese text and wanted to throw your hands up in despair, then this article is for you.

Even though the Chinese pronunciation isn’t as bad as you might have heard, and the grammar isn’t as trivial for an English speaker, actually gaining literacy in Chinese is a long, long journey (which is why I think it’s a good idea to start with children stories and move your way up).

Today I’m going to give you a guide that can help you at every stage of this adventure. Whether you’re just starting out or have already been learning for a couple of years, there’s always room to improve your ability to read Chinese.

How to Read Chinese in 5 Steps

Step 1: Characters and How They’re Made

Each character in Standard Chinese has a one-syllable pronunciation. In this article, we’ll be using the Modern Standard Mandarin readings (pronunciations) of the characters.

However, it’s important to know that the characters can be read aloud in any variety of Chinese – and in fact, many ancient poems only rhyme in non-Mandarin varieties.

Chinese characters are very frequently comprised of many parts. Take a look at something like 明 [míng] and you can see that it’s made of two parts.

On the left, 日 [rì], and on the right, 月 [yùe].

Let’s take the character 月. This character means “month.”

Digging deeper, though, it originally meant “moon,” which makes sense: lots of languages have a related root between “month” and “moon.”

The character 月 is also a radical. This means that it can and does appear in other characters to provide a hint as to the meaning or pronunciation.

明, for example, is a combination of a sun and a moon, and the meaning fits perfectly: “bright.”

Characters are made of radicals and other secondary components that may or may not provide more hints. Since the Chinese writing system has been around for thousands of years and endured hundreds of generations of language change, some of these hints are quite opaque nowadays.

Step 2: Learning Radicals and High-Frequency Characters

Now that you have an idea how characters are formed, you can build on this foundation by learning the whole set of radicals first.

There are officially 214 radicals used in the construction of Chinese characters, and it’s easy to find lists of these online. Many are used very infrequently as stand-alone characters, but you’re not wasting time by learning them.

By knowing their pronunciation and base semantic meaning, you’ll soon be able to make an educated guess at the pronunciation and meaning of characters you haven’t seen before.

For example, the character/radical 火 [huó], meaning fire, is frequently used as a semantic component. See if you can find the 火 radical in the words 烟 [yān] (a cigarette), 烤 [kǎo] (to roast), 炒 [chǎo] (to fry).

At the same time, you’ll also want to look at some lists of basic and frequently used characters. The Chinese government publishes character lists based on their HSK Chinese language test, which is a perfect place to start.

Step 3: High-Frequency Words and Collocations

You’ll quickly learn that the overwhelming majority of words in Mandarin are two syllables long. It’s only in more literary or poetic works that you run into a lot of single-syllable words.

Your next step is to use more vocabulary lists to begin learning the most common words. Of course, you can do this at the same time as step one.

I recommend learning lots of verbs and nouns first, if you have the choice. The other parts of speech are just as important, but once you memorize 150-200 really common verbs and nouns you should be able to see them popping up everywhere.

You need about 3000-5000 characters to be able to pronounce pretty much everything you come across. But you shouldn’t just learn from character lists, that would turn anybody off of learning to read Chinese.

Instead, when you learn a character, check in some online dictionaries to see in which words it commonly appears.

Let’s take the character 出, which means “to go out.” By itself, it’s not used very much if at all. But there are several words with 出 that you’ll run into all the time.

出门 [chūmén] (to exit a building), 出口 [chūkǒu] (an exit), 出租车 [chūzūchē] (a taxi), and 出发 [chūfā] (to set off on a journey), for starters.

Step 4: Building Reading Speed with Sentences

Next, you’re going to want to get used to Chinese sentence structure by reading a lot of sentences or very short pieces of writing.

The short format of sentences keeps you from getting lost in a longer text. It’s a real pain to work through a whole paragraph and then realize that you didn’t understand it because you were missing too much vocabulary.

The example sentences in a dictionary, coursebook, or web app are perfect for this. You should make an effort to collect interesting sentences from these and other reading resources, then review them regularly.

This will get your brain used to breaking down Chinese sentences into chunks. It takes a long time, no question about it. But the work here pays off.

Step 5: Read and Re-Read

Once you can break down a sentence into parts and understand most example sentences with the limited use of a dictionary, you’re going to need to do a lot of reading.

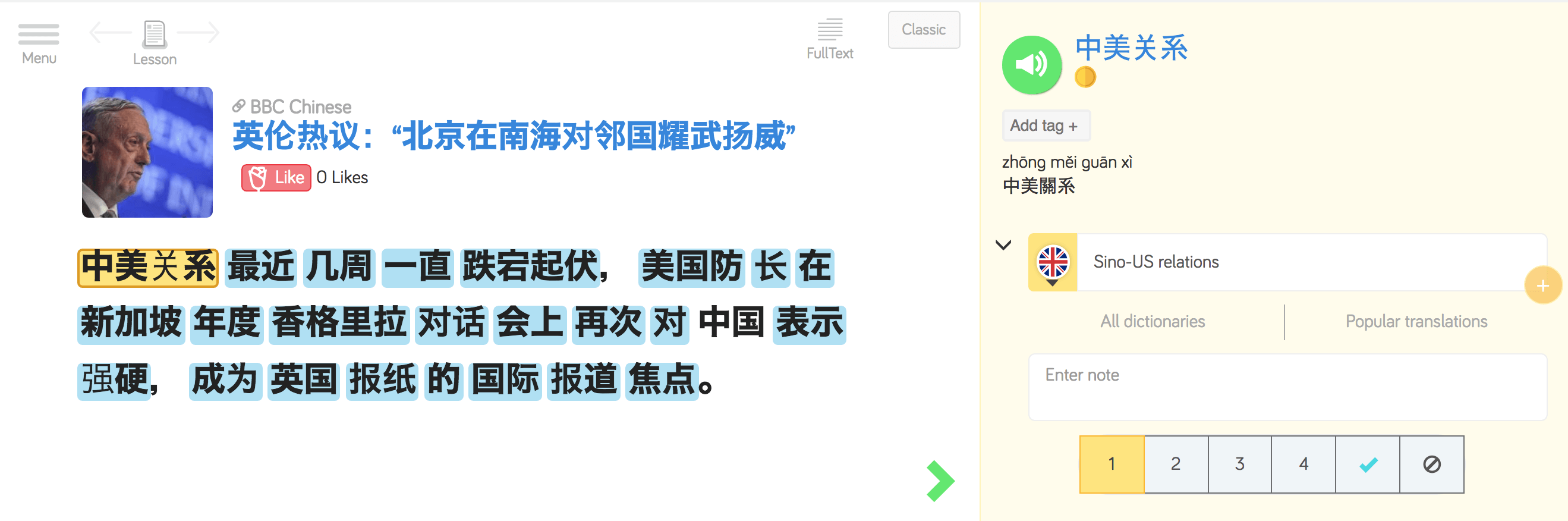

You can start with the Chinese materials here on LingQ. They’ve been curated to be of high quality, and the additional LingQ tools can help you keep track of known and unknown vocabulary.

Outside of these materials, you can also look for short news or light entertainment pieces on daily life topics. Things like recipes, fitness, and product reviews are great ways to get exposure to the natural language.

When you’re ready to move on to fiction, I strongly recommend finding Chinese translations of books you know and love. You need to get used to building up your Chinese reading endurance, even if the words are familiar to you.

Translations from your native language have the benefit of being structured in a way that you’re already used to. Narratively, the book is in your native language already, and you just need to decode the actual text. Chinese writing styles differ pretty heavily from Western norms when it comes to fiction, so it’s best to have a lot of practice before

By reading and re-reading a text, you’ll start to build reading speed. Reading speed is one of the most important skills you can have for any standardized exams – plus it’s always better not to have to spend long minutes on every page of text.

Learning to read Chinese takes sustained effort over a period of years, not months. Think of all the reading you’ve done in your native language – this article alone is more than 1100 words, a daunting figure for most people. But after all that toil comes Chinese literacy.

Learn Chinese Faster Using LingQ

Immersing yourself in Chinese doesn’t require you to travel abroad or sign up for an expensive language program.

However, it can be a bit tiresome to find interesting content, go back and forth between sites, use different dictionaries to look up words, and so on.

That’s why there’s LingQ. A language app that helps you discover and learn from content you love.

You can import videos, podcasts, and much more and turn them into interactive lessons.

Keep all your favorite Chinese content stored in one place, easily look up new words, save vocabulary, and review. Check out our guide to importing content into LingQ for more information. Check out LingQ to discover how to learn Chinese from content you love!

LingQ is available for desktop as well as Android and iOS. Gain access to thousands of hours of audio and transcripts and begin your journey to fluency today.

Alex Thomas has used the Chinese language in some way or another every single day for more than two years. He has no plans to stop.