How Long Does it Take to Learn Japanese?

こんにちは!My name is Sami; I was born in the United States and had never left until, about four and a half years ago, I went to Japan to spend my second year of university abroad. Today I live in Taiwan and use Japanese everydayーI’m nowhere near being bilingual, but if I woke up tomorrow and could only speak Japanese, my life would continue on basically as normal.

The story isn’t quite that simple, though. My second language is Spanish and I originally planned on going to Mexico, but after finding out that I couldn’t, a dart and a globe sent me off to the land of the rising sun. Although it’s a very important part of my life today, I originally went to Japan sheerly because it was cheaper than staying in the USAーupon arriving I didn’t even know that sushi or Pokémon were Japanese.

It was, genuinely, a start from zero.

Today I’ll retrace my journey and share what made Japanese click for me so that, hopefully, you’ll finish with a better idea of where you are and where you’re going.

How many hours does it take to learn Japanese

I’d really like to lay out some concrete numbers for you, to tell you that you’re this many hours from a nice conversation or that many years from eating Natto without plugging your nose, but the good and bad news is that no matter what I say, your mileage is going to vary.

I wish I could just refer you to people who are smarter than me, but that doesn’t necessarily solve all of our problems, either. While the JLPT association itself estimates that it will take around 900 hours to pass the N1, the US government suggests a much more conservative 2,200 hours and a study of full-time language students in Japan found that, for students with no prior background in Kanji, passing the JLPT N1 took 3,000-4,800 hours on average.

What I can tell you is that, regardless of where you fit into the mix, it’s going to take time. Depending on what you want to do with Japanese, it could take more or less time. The quickest route possible is to figure out what you want to doーa bigger task than it seemsーand focus on making consistent, active steps towards getting there. Fluency is a big goal comprised of many separate skills and you’re much closer towards confidence in any one of these individual skills than you are to fluency.

Wherever you’re going, step one is finding your thing and doing it.

Pro-tip: An easier way to read Japanese

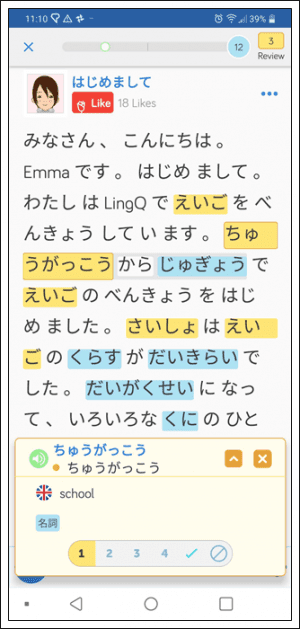

Reading Japanese can be tricky, especially if you’re a beginner. After learning hiragana and katakana, you’ll be able to start reading beginner content. However, you may come across kanji once-in-a-while which can disrupt your flow, especially if you have to stop and look up the word in another dictionary. That’s why there’s LingQ to help you read Japanese easier:

-LingQ allows you to look up words with a single tap

-You can choose a variety of dictionaries

-Text-to-speech allows you to instantly hear how the word is pronounced

-Blue words you come across are “new”, tap them to turn them into yellow words and save them for review

LingQ comes with 100s of beginner lessons that include both text and audio so you can listen to the transcript as you read. This means you can improve your listening and reading skills at the same time, all in one place.

Reading interesting content kick-started my Japanese

My “thing” is reading, and both my approach to Japanese and my ability in it changed dramatically after discovering that.

I finished my first year abroad in Japan at a solid N4 level and then went home where, very busy and without a Japanese program, I focused on building a strong vocabulary core and learning the Kanji with Anki because it was the only thing I felt comfortable doing on my own.

The following year I returned to Japan and was placed a few classes higher than I should have been. Noticing how much stronger my vocabulary was than all of my other skills, my teacher recommended that I start reading in Japanese so that I could pick up grammar in context.

Before long I discovered a training-wheels book called Read Real Japanese and I liked one of the stories inside, Hyakumonogatari by Kaoru Kitamura, so much that I brought my “maybe” N3 Japanese to the head of the Japanese literature department and asked for recommendations. He read the story and told me that another author, Yuuki Shouji, wrote tons of stories with similar twists.

I had previously plateaued so quickly because, even living in Japan, I didn’t really need Japanese for anything. After finding “my thing”, however, I suddenly found myself in a situation where I couldn’t get something I really wanted without Japanese. That was all it took: my progress skyrocketed.

Pro-tip: Find your “thing” (anime, drama, J-pop, and so on)

I’ve mentioned that my thing is reading, which is essential for learning any language. Now, your thing may not be Hyakumonogatari by Kaoru Kitamura, and that’s fine. What’s important is that whatever it is you enjoy, incorporate that into your studies.

If you want to read Murakami or Soseki in Japanese, for example, hiragana and katakana are your first hurdles to overcome. If you want to enjoy your favorite drama or anime, then you’re going to need to spend time actually watching anime and Japanese dramas.

LingQ is the best way to learn Japanese online because it lets you learn from content you enjoy!

You can also use LingQ to import your favorite content and create interactive lessons. Below, I’ve imported the popular anime, Shirokuma Cafe into LingQ. LingQ not only turns the transcript into an easy-to-read lesson but it also imports the audio as well. As you read, you can listen to the dialogue!

This guide to importing explains how you can use LingQ to study using content you love, take a look.

How I study Japanese

My schedule is a bit different now, given that I live in Taiwan and am focusing on Mandarin. Aside from that, my days look like this:

9:00ー10:00 is my commute to work. I use public transportation and spend this time reading.

The first half of my day is spent working freelance; I spend 30 minutes to an hour of this time speaking Japanese with a tutor. I take 2 or 3 lessons per week and meet with different people for different purposes. (This is new to this year).

My teaching day begins at 14:00 and I have a lunch break from 16:00 till 16:30, during which time I work through one lesson of a workbook while eating. My favorite ones are called Drill & Drill, which I used for both grammar and reading comprehension, starting from N5 and working my way up. Series by Kanzen Master and Sou Matome are also popular, so pick one that works for you. These are supplements: small, consistent things done to support another more important thing. In my case, that means understanding the stuff I’m reading with less effort and more enjoyment.

18:45ー20:15 is my return trip home and, depending on my mood, I might spend this time reading, watching Japanese dramas or focusing on my current thing, Japanese comedy skits. One of my favorite groups is called Unjashーif you haven’t tried Japanese comedy before, check out this English subtitled version of Through the Paper Wall.

I spend a good chunk of time each day just… well, waiting. Walking to bus stops, waiting in line for food or the bathroom, killing a few minutes before class starts. I give this time to Anki, mobilizing time that would otherwise be wasted.

I struggle sleeping, so I also read for 15ー20 minutes before bed. My “bedtime book” is something that I find easy and read only before bed.

Many of my friends are Japanese students or Taiwanese people that speak Japanese, so if I go out with friends during the week, I’m also practicing Japanese.

As I said before, my thing is reading, and after I discovered that, I built my entire schedule around it. This enabled me to make much quicker progress in the areas of Japanese that were important to me, leading to me spend more time in Japanese. Now that I’m comfortable reading I’ve moved to a different skillーpronunciationーand am focusing on that.

The Five Levels of Japanese Proficiency

Elementary proficiency

Reaching this level of proficiency means that you can navigate daily life and satisfy your needs without fear. You can ask any sort of simple question and also pick out the most pertinent, important information from the reply. Not a lot of conversation will be going on at this point, on behalf of a limited vocabulary and lack of important grammar points, but with a patient partner and some creativity on your end, you might just know enough to surprise yourself from time to time.

This level is roughly on par with the JLPT N4, so content wise, you should be looking to have finished Genki I and Genki II or Minna no Nihongo I and Minna no Nihongo II.

How long does it take to achieve?

While your mileage may vary, my progress personally fell quite closely in line with the most conservative estimate from above, suggesting 575-1,000 hours of study to pass the N4. This milestone is also my most memorable so far as it came about in a crazy way: I had been walking barefoot and stepped on a bumblebee, whose stinger got stuck in the arch of my foot. It turned out to not be such a big deal, but while I was at the nurse’s office, I ended up having my first genuine conversation. It was equally parts broken, meaningful and hilarious.

7 months leading to The Conversation:

– 10 hours/week of class = ~280 hours

– 1 hour/day studying alone = ~200 hours

Given that I was living in Japan at the time, I had also had daily opportunities to practice this basic grammar/vocab by ordering food in the cafeteria, seeing signs in the subway and having to ask for directions in the city. Totalling all that would probably amount to another couple hundred hours.

Limited working proficiency

This is essentially a mastery over whatever might be expected to come up in daily life, and that’s a cool place to be. Most conversation becomes possible without significant strain and you can consume Japanese media with focus and patience, but you’re not quite comfortable using all the grammar you’ve learned and still find yourself missing words here and there. There is a long way to go, but you’ve reached a level where you’re independent enough to begin going off in your own direction.

ILR 2 proficiency is around the JLPT N2 proficiency with one significant caveat: the JLPT requires no production (writing/speaking) whereas the ILR expects that you’ll be able to handle most daily communication with confidence. Depending on how you’ve been learning up until this point, you might need to put significant effort into conversation practice.

How long does it take to achieve?

At this point, the study I referenced suggests that even quick students will struggle to hit this milestone in less than 2,000 hours. I feel like I was around this level upon leaving Japan for the second time, at which point I found myself able to read normal books in Japanese with a lot of effort and found conversations enjoyable. At this point Japanese was in a strange place for me: despite still being an incredibly “foreign” language, it was very much beginning to feel like a part of me.

Twelve months at home:

– 30 minutes+/day practicing kanji/vocab = ~ 200 hours

10 months in Japan:

– 15 hours/week of class = ~600 hours

This brings my official total to 1,300 hours. That being said, being the lone foreigner in boxing/dance club, going out with friends and (painfully) beginning to read, I probably spent another 1,000 hours on Japanese during those last 10 months via immersion.

Professional working proficiency

This is where things get serious: ILR 3 proficiency is the metric used when we talk about how many people in the world speak a given language. Being here means being able to say I speak Japanese. Period. No ifs, ands or buts. There will still be things you don’t understand and things you don’t know how to do, but you can build on the Japanese you have to figure it out. Perhaps it’s apt to say that you’ve indisputably attained a plot of land, but you haven’t built a full house on it yet. You’re missing a lot of rooms for lack of need and time, rather than ability.

The same caveat exists from before, that the JLPT doesn’t test your ability to produce Japanese, gets bigger as we go on. This level of proficiency entails not only you being comfortable with Japanese in a variety of ways, but also that the people you’re communicating with feel comfortable with you. They’re no longer talking with a foreigner, they’re just talking with someone in Japanese.

How long does it take to achieve?

I feel that this level is where I’m at with Japanese, so from here on will be a little bit of speculation in addition to reflection.

9 months in Russia:

– 1 hour/weekday practicing Kanji (morning commute; focus on writing)

– 2-3 hours/weekday of extensive reading (commute between classes/home)

– 5 hours/week socializing with Japanese students/Russian students of Japanese

– 180 hours kanji + 450 hours reading + 180 hours socializing = 810 hours

8 months in Taiwan:

– 10 hours/week of extensive reading (morning/evening commute)

– 2 hours/week of 1:1 tutoring

– 2 hours/week of practice in workbook

– 3 hours/week of watching drama/comedy skits

– 320 hours reading + 64 hours 1:1 + 64 hours practice + 96 hours watching = 544 hours

Total since beginning: 2,600 routine hours (I definitely did this) + 1,500-2,000 immersion hours = 4,100 – 4,600 hours, placing me once again right within the conservative estimate from earlier.

Full professional proficiency

In the previous section I mentioned having a plot of “Japanese land” and a house that was missing many rooms. By the time you get here, your house will have grown into a mansion: you’ve got all of the rooms you need and more. You make virtually no linguistic mistakes (be they in pronunciation, grammar, sentence structure or vocabulary) and can fulfill basically any task smoothly without preparation.

That being said, you’re still not quite being taken for a native speaker. The problem at this point isn’t your understanding of the Japanese language but more often of Japanese culture. Your lack of understanding of some given specialized area of Japanese culture occasionally puts you in situations where, despite understanding everything that is written or said, you don’t understand why it’s funny, relevant to the topic at hand, or what it means . While the problem is occasionally what is said (slang, idioms or colloquialisms), it’s more notably what isn’t said (references to Japanese culture, history, etc, that are lost on you).

How long does it take to achieve linguistically?

Linguistically speaking, I don’t think that I’ll reach this point until after I’ve worked in Japan, in Japanese, for a year or two. There are two major problems I see preventing me from being there now: confidence and need.

While I’m confident that I can consume basically any information or discuss any topic, I’m not so confident that I’m ready to rest the face of a business on this ability. Furthermore, I’m already proficient enough that I can do whatever I want in Japanese without much effort, from conversing to creative writing. The problem is more about being able to do all the things I haven’t yet had a need or cared to do because Japanese exists only in my social and personal life, not my professional one.

Frankly speaking, most people don’t have any need to speak a language this well. I’m confident that I never will, either, unless my livelihood depends on it. Why spend a lot of time and money making a super model train set if you don’t actually have any trains?

How long does it take to achieve culturally?

Culturally speaking, the issue becomes one of breadth. I don’t really care about the history of Japan, I can’t name all of the prime ministers or the scandals associated with them, I don’t really understand the loss of identity Japan must have underwent as it became westernized and there are a million little things like this that I don’t even know I don’t know about. I’m not really interested in these things, but if I want to get to this level, I’ll need to learn about them, anyway.

Before getting to this level, you should pretty much already know what to say. This level is all about really understanding exactly how you should say it and why you should say it like that so that you can do it smoothly, without explanation, no matter what “it” is.

Native or bilingual proficiency

A person on this level of proficiency has total fluency, period. While it might be obvious that you’re foreign, you’re somehow accepted as being also Japanese. Whether the topic is car engines, baking, a sitcom from the 80s or stereotypes about the way that old ladies in Touhoku talk, there is basically no difference in asking you vs asking a Japanese person. Your proficiency in Japanese is equal to, if not greater than, your native language.

How long does it take to achieve?

Again, the problem here is of the incredible depth involved.

Linguistically, it isn’t enough to know how to say anything and everything with ease, a native speaker can say one thing in ten different ways on the fly depending on the nuance they’re going for. If in the last level we had a fully developed Japanese body, in this one we’ve become a contortionist.

Culturally, I don’t even know how to discuss this. Somehow you need to come to understand what it means to be Japanese without actually being Japanese: to understand life in a way that Japanese people grew up experiencing collectively, whereas you began just peeking in from the sidelines.

Japanese people spend their lifetimes becoming Japaneseーwhether they’re six or sixtyーand the only thing I feel comfortable saying is that this level of proficiency takes a lifetime. If your life isn’t Japanese right now, you’ll have to grow a new one to reach this level.

Conclusion

In discussing how long it would take to learn Japanese, I’ve frequently referenced this idea of need. After all, we don’t necessarily want to speak Japanese, we want to do (thing) for which Japanese is a perceived medium. I believe that each person will learn Japanese as well as they need to, whether this need comes from environmental pressure, a need they’ve created for themselves, or a lack thereof.

The quickest way to discover how much Japanese is necessary to fulfil your own needs is simply to jump right in and discover how deep the water is.