Russian grammar 101

Just like English, the Russian language has a grammatical structure that is too complex for one blog post. However, we’ll try to give a general outline of the Russian grammar and describe the principal differences between Russian and English.

Masculine, Feminine or Neuter?

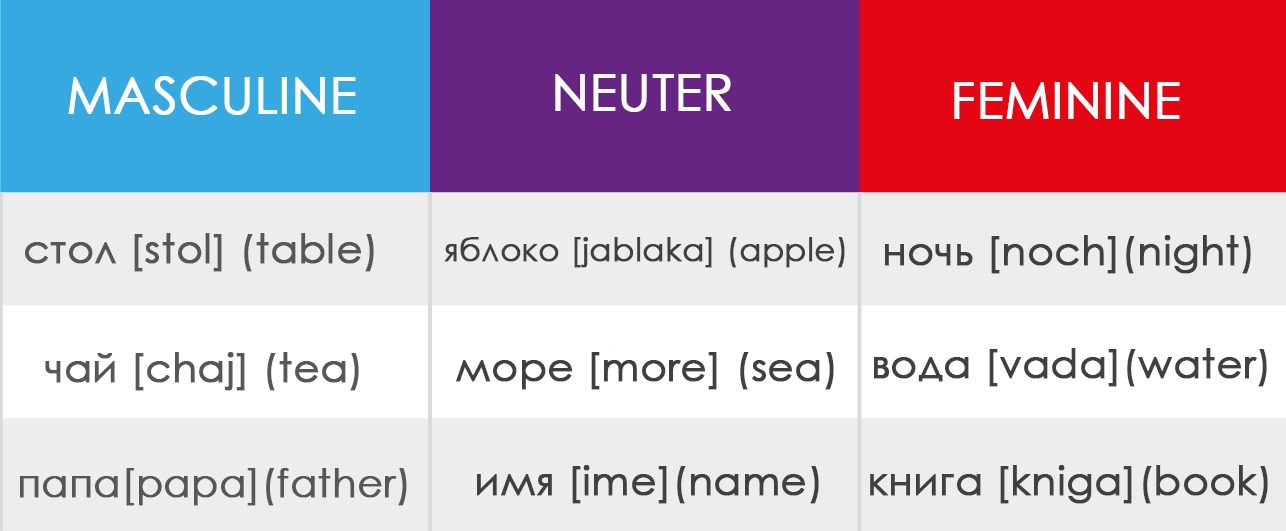

English does not have a grammatical gender system, while Russian has three genders:

In order to distinguish the genders, one has to learn the patterns of inflections for each gender.

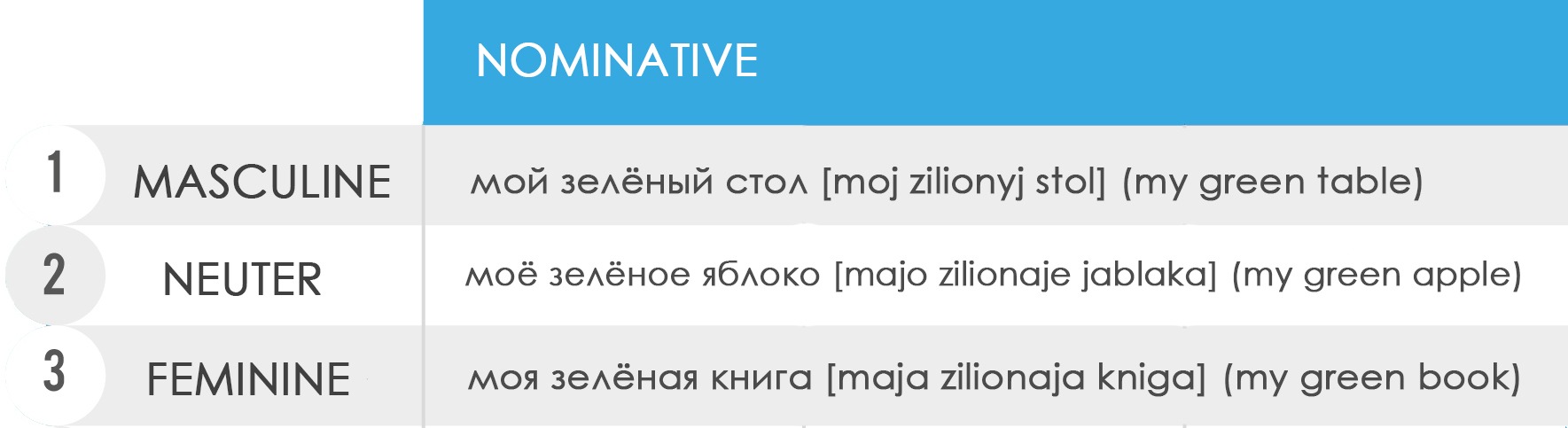

Furthermore, Russian adjectives and most pronouns also take a gender form that is “triggered” by the noun they are used with:

As you can see, мой, моя and моё are masculine, neuter and feminine forms of the possessive pronoun мой (my); зелёный, зелёное and зеленая are masculine, neuter and feminine adjectives respectively.

As you can see, мой, моя and моё are masculine, neuter and feminine forms of the possessive pronoun мой (my); зелёный, зелёное and зеленая are masculine, neuter and feminine adjectives respectively.

Analytical vs. Synthetic Language

English is an analytical language. This means that grammatical relations between words are conveyed with the help of prepositions, conjunctions, articles, auxiliary verbs, function words and the word order.

For instance, the below two sentences have absolutely different meanings:

1) Tom hit Paul.

2) Paul hit Tom.

Thanks to the word order, an English language speaker perceives the subject and the object of each sentence.

In Russian, relations between words are expressed by means of inflections. This makes it a synthetic language. Word order does not have such an important role as it does in English.

In Russian, you can say either of the following:

1) Том удалил Пола.[ Tom udaril Pola] or Пола ударил Том [Pola udaril Tom] = Tom hit Paul.

2) Пол ударил Тома. [Pol udaril Toma] or Тома ударил Пол[Toma udaril Pol] = Paul hit Tom.

A speaker of Russian understands what the subject is and what the object is in a sentence thanks to the ending(s) of noun(s)/pronoun(s). For instance, in this case the genitive ending -а signifies the object.

How Many Cases are there in Russian?

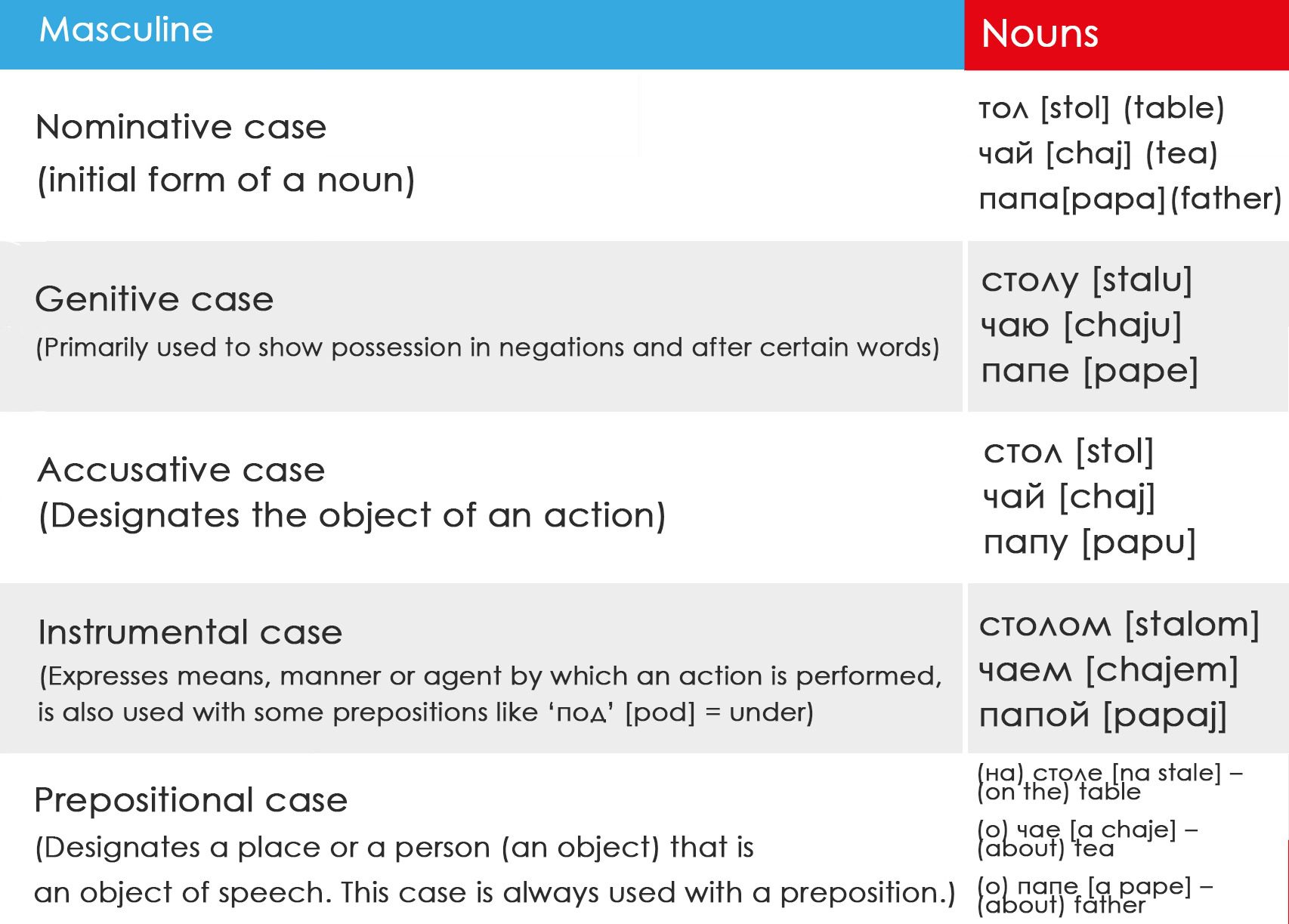

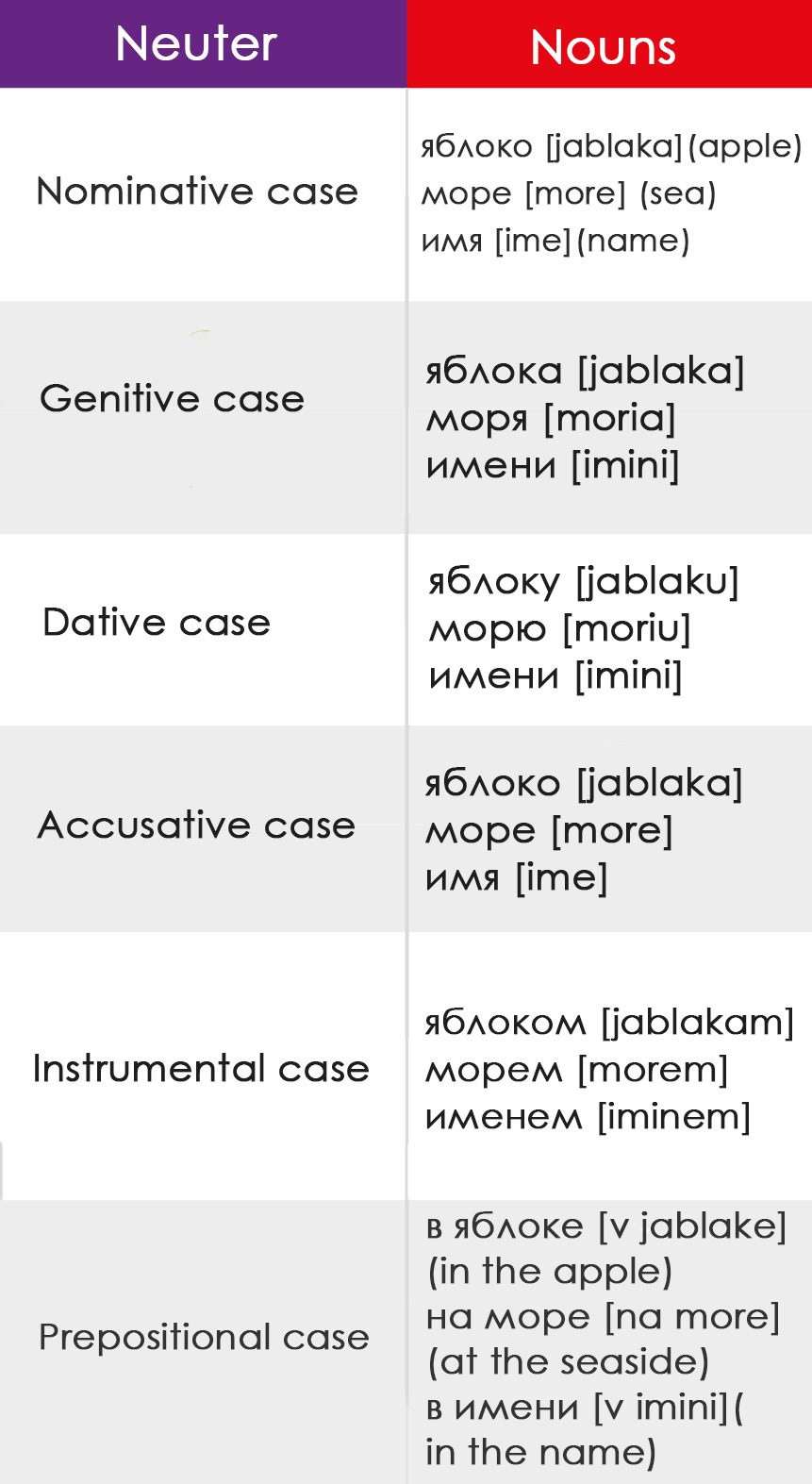

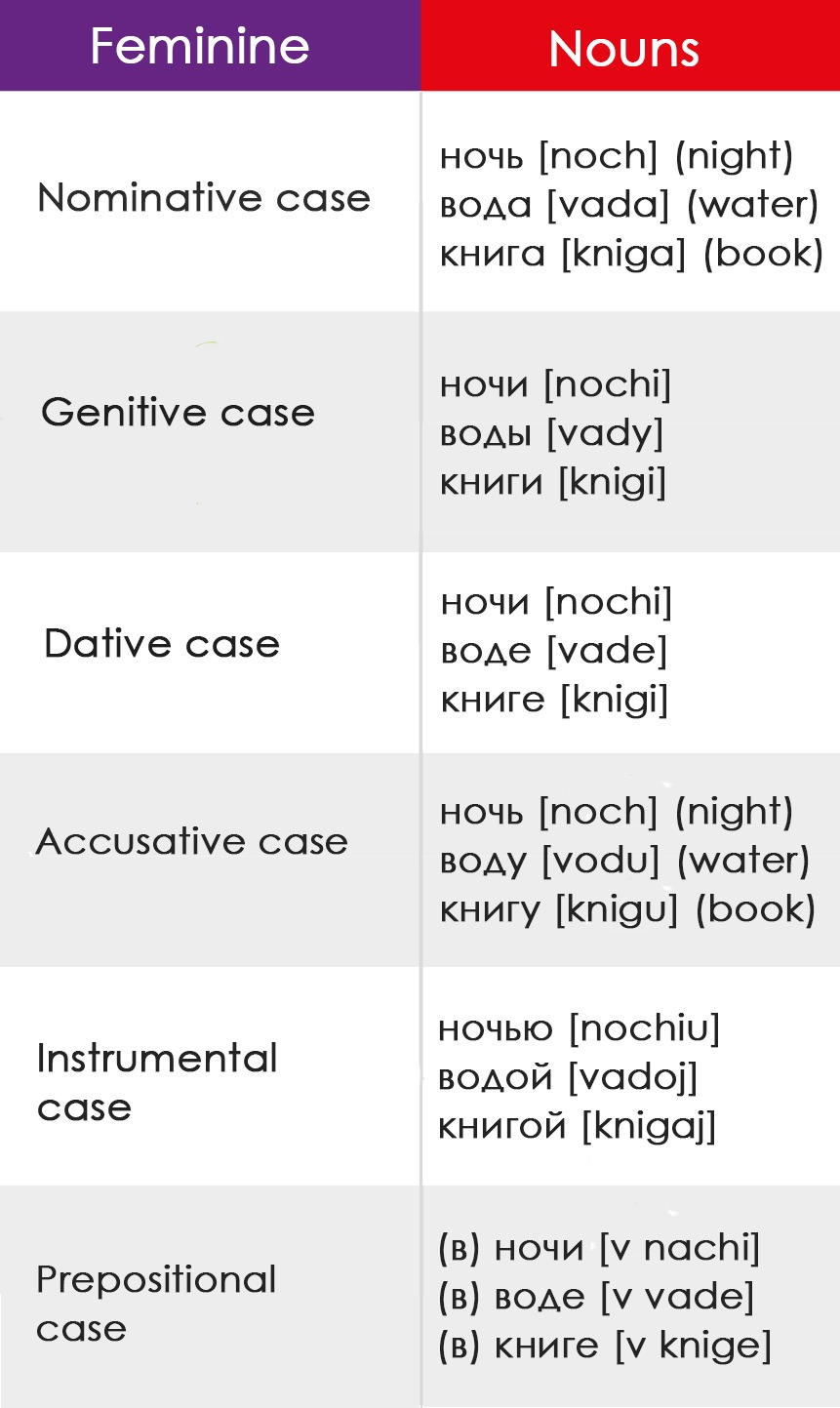

Russian has six cases. Nominative, genitive, accusative, instrumental, prepositional, and dative. In the tables below you can see how noun forms change depending on the case.

You might have noticed in the tables above that word stress is not fixed in Russian, and sometimes it changes depending on case. This presents a challenge for foreigners.

Pronouns and adjectives are also declined along with the noun they are used with. Adjectives and pronouns agree with nouns not only in gender and case but also in number (plural or singular).

Adjectives and Adverbs

Just like in English, Russian adjectives and adverbs modify nouns and verbs or adjectives respectively. They also have the comparative and the superlative forms.

Adjectives agree with nouns in case, gender and number. Adverbs do not agree with any other part of the sentence (they have only one form, no gender, no declension, etc.):

Высоко в горах [vysako v garakh] – high in the mountains,

лететь высоко [litet vysako] – to fly high

What about Verbs?

In some respects, Russian verbs are less tricky than their English counterparts. Because there are no continuous, perfect and gerund forms in Russian, verbs have only four forms:

Infinitive: писать [pisat’] – to write

Present tense: я пишу [ja pishu] – I write/I am writing

Past tense: я (на)писал(masculine)/я (на)писала(feminine) [ja napisal, ja napisala]– I wrote(I have written/I had written)

Future tense: Я напишу [ja napishu] – I will write/ I am going to write

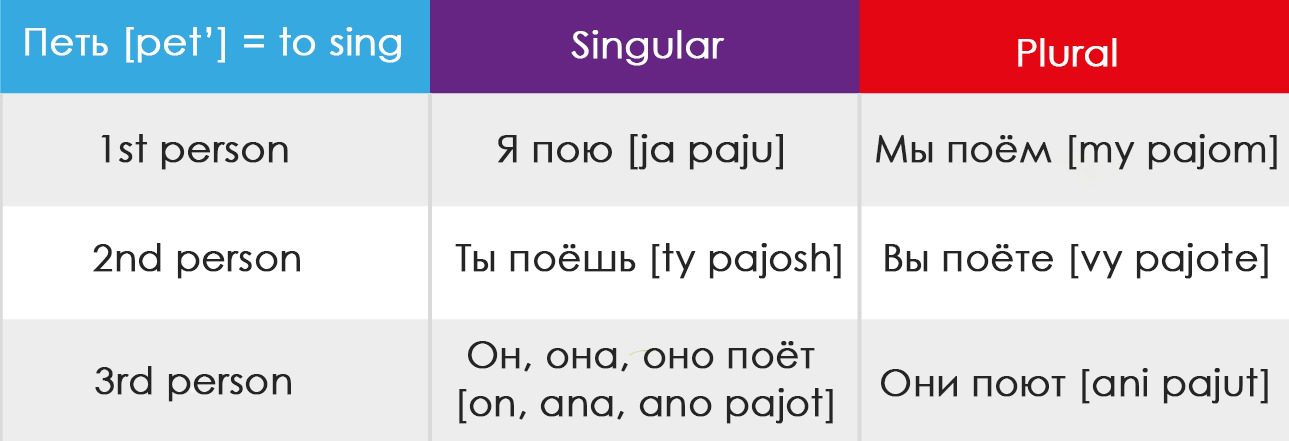

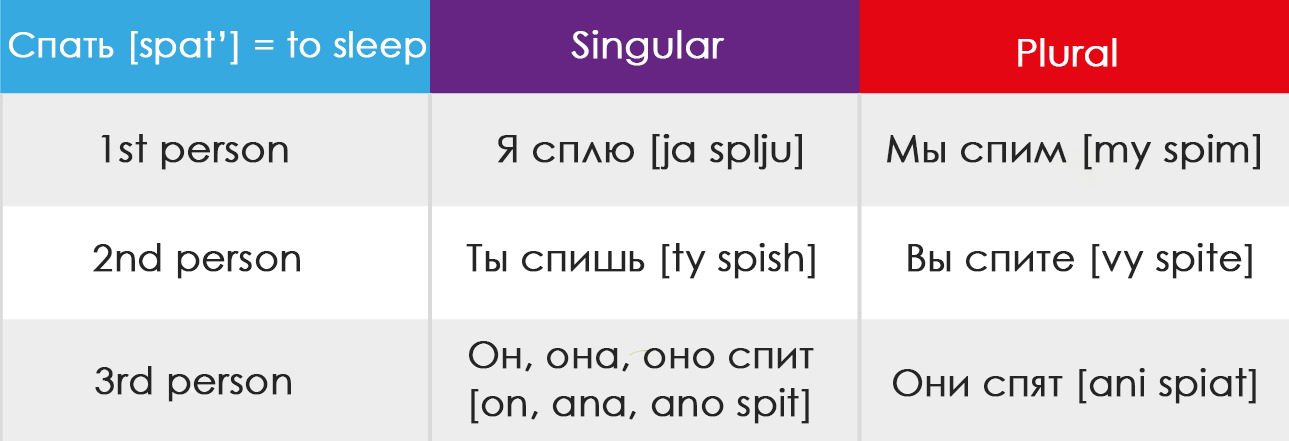

On the other hand, Russian verbs have two conjugations, which means that different conjugations have different forms of person and number. In some ways conjugation of verbs is similar to the declension of nouns.

Here are some examples of how Russian verbs are conjugated:

In the 1st conjugation, verbs in the 3rd person plural end in -ут,-ют, and this gives you an of idea how to conjugate all other forms of the verb, i.e.

In the 2nd conjugation, verbs in the 3rd person plural end in -ат,-ят, and this helps you to identify them and conjugate correctly:

In the past tense, verbs also have masculine, feminine and neuter genders in the 1st , 2nd and the 3rd person singular:

Another peculiar thing about Russian verbs is that they have two aspects: imperfective and perfective. Any verb has both forms. The imperfective form signifies an action that is repeated or habitual, an incomplete action, or an action the result of which is not important i.e. ‘читать’ [chitat’] = to read, писать [pisat] = to write.

Another peculiar thing about Russian verbs is that they have two aspects: imperfective and perfective. Any verb has both forms. The imperfective form signifies an action that is repeated or habitual, an incomplete action, or an action the result of which is not important i.e. ‘читать’ [chitat’] = to read, писать [pisat] = to write.

The perfective aspect is used to describe a single finished action or an intention to complete an action in future: ‘прочитать’[prachitat’], ‘написать’[napisat].

Compare these two sentences for a better understanding:

Я люблю читать [ja liubliu chitat] – I like reading

Мне нужно прочитать эту книгу для экзамента [Mne nuzhna prachitat etu knigu dla egzamina] – I have to read this book for the exam.

***

We hope that you are feeling challenged and not discouraged about learning the Russian language. Despite all its differences with English, Russian grammar is logical with clear rules.

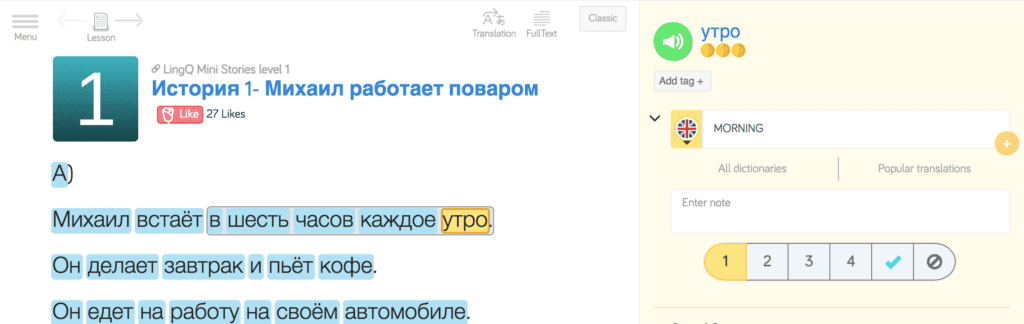

The best way to learn Russian grammar is through repeated exposure to interesting Russian content. You can get this even as a beginner on LingQ. The Russian Mini Stories are a great place to start. Grammatical structures will become natural the more you see them in different and interesting contexts. Give it a try!

Ievgeniia Logvinenko is passionate about languages and holds a Master’s degree in English philology. In addition to English, she speaks Russian, Ukrainian, Polish, German and basic French.