Chinese Slang Vocabulary for Absolute Beginners

A little bit of Chinese slang vocabulary can go a long way.

Imagine, strolling along a Shanghai sidewalk or motoring along on a Taipei street.

Chatting with the men playing chess in the park.

Laughing with the clerk at the convenience store.

At ease with the language, the culture, and life itself.

An intoxicating fantasy, isn’t it?

And certainly one that takes quite a bit of above and beyond when it comes to the language. You’ll need more than what appears in your textbook, that’s for sure.

Well, today I’m here to tell you that that goal’s not so far away after all.

All you have to do is sprinkle your already respectable Chinese with a little bit of slang.

In this article, you’ll learn 8 new slang words that show you’ve really gone the extra mile to connect with the local culture.

六六六 (Liùliùliù): Awesome, amazing!

It’s an unfortunate coincidence that the number 666 is associated with awful things and bad luck in Western culture. In Chinese, it’s used as an exclamation of amazement.

It does turn out, though, that just one 六 usually gets the job done if saying the full thing makes you uncomfortable.

牛(牛逼) (Niú (niú bī)): Amazing, incredible!

There’s a funny story behind this term. If you dig deep into the origins of this word, you’ll quickly find that it can only be translated as a crude anatomical reference.

However, the term has been around for long enough and has become widespread enough that it’s lost all shock value. Today, you’ll see it in advertisements and hear it from children all the time.

If you’re worried about offending anyone, you can drop the 逼 and just say 牛as in 最牛 (zuì niú)“the coolest, the strongest). Everyone will understand.

機車 (Jīchē): A stickler (used in Taiwan)

This is one I learned way back in university, from a professor who originally hailed from Taiwan. Motorcycles and scooters are a common sight in Taiwan. Just imagine someone right behind you on a motorcycle, breathing down your neck and driving from the backseat.

It’s kind of similar to the thought evoked in English when you say “so-and-so is riding us hard to get this done.”

干嘛? (Gàn ma): What are you doing, what are you up to?

嘛 is an interesting character in my opinion. It’s an ending particle pronounced just like 吗 (ma), but it’s most often used in this set phrase or as an alternative to 吧 (ba). It sometimes has a hint of annoyance or impatience. 走嘛! Let’s go already!

That hint of rudeness plays into a crucial part of Chinese culture. It’s very common for good friends or coworkers to pretend they’re annoyed or sad at others – just for a second, just to get a rise out of the other person.

“小王?” “叫我干嘛?” (“Xiǎo Wáng?” “Jiào wǒ gàn ma?”)

“Xiao Wang?” “Whaddya asking me for?”

臣妾做不到啊 (Chén qiè zuò bù dào a): Princess is too tired, princess doesn’t wanna.

This comes from the world of Chinese television dramas.

臣妾is a Classical Chinese way for a woman in an imperial court to refer to herself. In ancient times, (or perhaps just ancient literature) people had a wide and elaborate range of pronouns to use for themselves and others in order to convey respect and social status. This one means “your servant.”

So just imagine a pouty Chinese princess laying back on her cushions and saying “I simply can’t.” That’s what people are trying to evoke with this phrase.

土豪 (Tǔháo): Nouveau riche

Literally “earth luxury.” That makes a bit more sense once you understand that 土“earth” is itself a synonym for “tacky” – as in decorations, jewelry, even entire houses.

However, this is just used for people – someone’s possessions may be 土, but only because they’re 土豪 and don’t understand the subtleties of social class yet.

扑街 (Pū gāi): Buzz off

Taken literally, “throw yourself at the road.”

The dictionary will tell you that these characters are pronounced pū jiē in the standard dialect of Beijing. The gāi pronunciation isn’t used in Beijing or the northeast, rather, it’s used pretty much everywhere else. It’s an older pronunciation that shows up in Cantonese, Wu, and Min varieties of Chinese as well.

This expression is pretty harsh – don’t use it lightly on people you don’t know.

老司机 (Lǎo sījī): An old hand

Literally “old driver.” The origin of this phrase was actually a mystery to me for a while because I kept hearing it used for people who were all sorts of things. Chess, video games, even sweeping a floor.

Only later I took a cab ride and fully understood. The driver asked me the location exactly once and didn’t even check his map a single time. We kept up a conversation as he effortlessly weaved through endless Xi’an side streets, getting me to my destination with time to spare. That guy was a 老司机 for sure.

Bonus:

….死宝宝了 (…Sǐ bǎobǎole): Way too ….!

You might already be familiar with the [adjective]死了 construction in Mandarin, literally [adjective] to death. It’s just a common exaggeration of the effect of some adjective: 饿死我了 (è sǐ wǒle) – I’m starving!

However, just like in the 臣妾 example, you can make this significantly “poutier” by replacing 我with 宝宝 (bǎobǎo) – literally “treasure” or “darling.”

冷死宝宝了!

lěng sǐ bǎobǎole!

Darling is too cold!

If you’re a man saying this, you’ll get huge laughs because men simply aren’t expected to put on any kind of pouting show. Just don’t overdo the act.

Of course, these entries only really scratch the surface of the incredibly complex world of Chinese slang. In researching this article, it turned out that most of the slang words I was able to come up with were either only used in some regions or wholly unprintable.

And it’s hard to pick these things up as a foreigner unless you’re already comfortable with the standard language. You have to have a barometer of sorts to know what’s okay to say in every context and what’s only okay in some.

Chinese Slang Vocabulary on LingQ

By far the best way to pick up that knowledge is to surround yourself with interesting and authentic native material like the stuff you can find on LingQ. You can’t learn the natural language without seeing and hearing it.

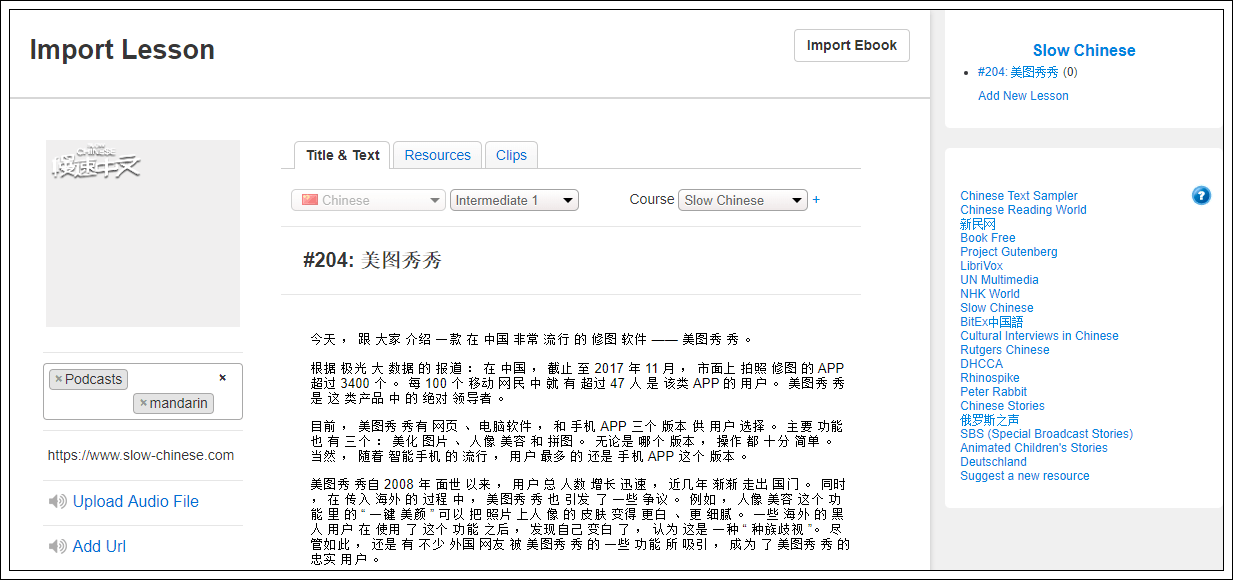

If you can’t anything that interests you in LingQ’s lesson library then you can import your favorite content. For example, there are a number of great Chinese podcasts which you can find all over the internet. Find one that you enjoy and import it into LingQ. All you need is the audio and the transcript.

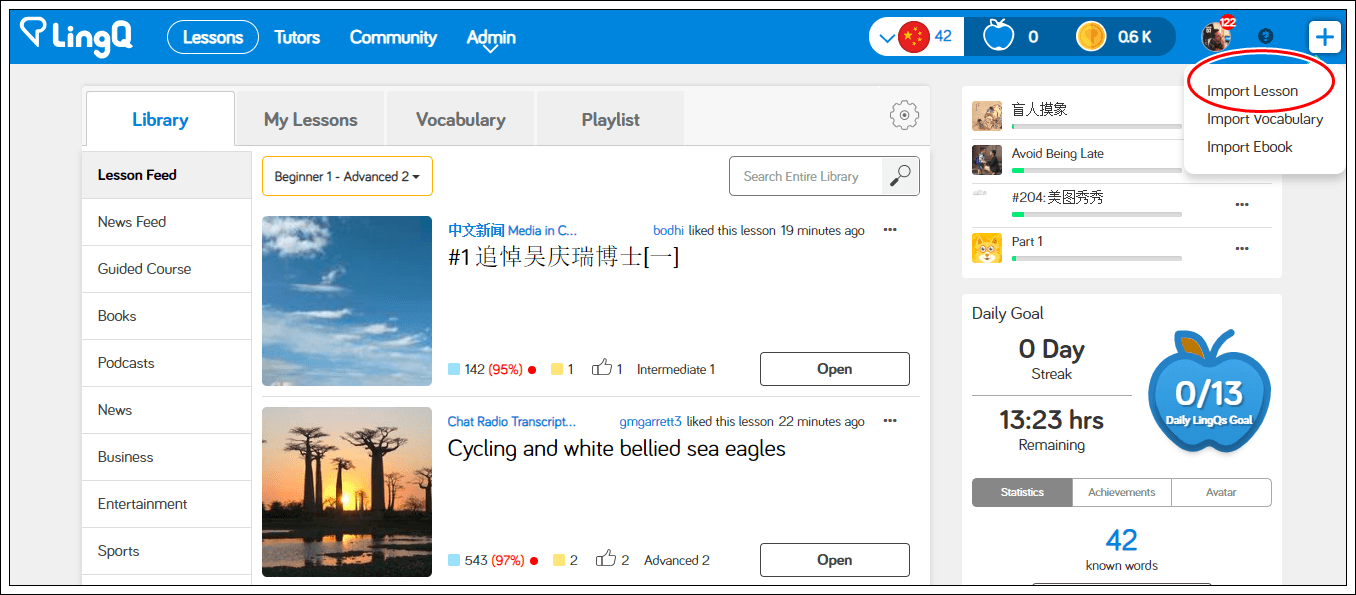

For example, Slow Chinese is a popular podcasts that also provides transcripts. If this is a podcast you enjoy, go to LingQ and click the import button at the top right of your dashboard.

Check out LingQ to discover how to learn Chinese from content you love!

From there, copy and paste the transcript into the text field. You can also add pictures and audio as well.

Hit save and open and you’re ready to start your new lesson using content you enjoy! Also, you can go through the lesson on mobile by downloading the LingQ mobile app. Good luck!

***

Alex Thomas lives in China and always has his ears open for new words. He speaks German, Mandarin, and Indonesian, and is working on Vietnamese.