How to Learn Japanese

Although I write about how to learn Japanese today, I was never actually interested in languages growing up.

I loved music and, entering college, joined a performance-oriented dancing club that happened to do a lot of Latin stuff. We spent weeks working single routines and, at some point, I began wishing that I understood the rhythms I was rumba’ing to. Enter Spanish.

I memorized the song we were dancing to – not a difficult feat given that I heard it hundreds of times a week – and then a few others. All I cared about was having a deeper

connection to what I was dancing to, it wasn’t about language yet, so I just slowly continued memorizing Spanish music and figuring out the grammar as I went. Before long I’d learned a few dozen songs, found myself in Japan (that’s a plot twist for another day) and joined a Spanish course to make friends.

Since then I’ve had adventures in Japanese, Russian and Mandarin. Although those journeys have all looked very different, they all began with music.

I keep coming back to music because I think it’s the best way for a beginner to get into a new language: songs are fun, accessible, repetitive and brief.

In this post I’m going to walk you through what my language learning looks like – first in theory, followed by hands-on examples.

How to Learn Japanese: Why it was easier to learn than Spanish

Although it may sound odd – Japanese is supposedly much more difficult for English speakers than Spanish, after all, and I’ve personally put nearly 5,000 hours into it – but Japanese has been much, much smoother sailing than Spanish was. Incomparably so, comically so, dramatically so. The reason for this lies in the perspective Spanish gave me on the language learning process.

You’ve probably heard that the first language you learn will be the hardest one and, furthermore, that it gets easier and easier to learn languages the more of them you get under your belt. I’ve found this to be true, and I think that it largely boils down to this idea of process. Process involves knowing what each step of the language learning journey entails, what hurdles will come up along the way and how to get over them.

Learning a language is sort of like plotting a course across the sea. The first time you do it you don’t have a map; you’re a pioneer, filling it in as you go. You stumble onto an island with useful resources and add it to the map, later you come across some trepid waters and (with quivering hands) put that on the map, too. Sooner or later you’ll have something resembling a real map and, with each new voyage, you gradually refine it. You know where to set off, which harbors to make for and which winds to put behind your sails to get there.

That’s huge, and a beginner doesn’t have that. As Seneca the Younger, a Roman stoic philosopher, put it:

When a person does not know what harbor they are making for, no wind is the right wind.

Step one, then, is identifying a few harbors – both to break your journey into more digestible chunks and also to give you a bit of direction.

But first, the most important thing you should be keeping in mind, no matter what stage of the journey you’re at:

Practice Doesn’t Make Perfect

Struggling learners are often told that they’ve just got to tough it out, to consume a lot of content and then they’ll eventually (magically) iron out whatever issues they have. It doesn’t quite work like that, though. Practice is important, but what’s more important is that the practice you’re doing actually addresses the source of whatever problem you’re having.

To borrow the metaphor from above, if you aren’t going towards any harbor in particular, or just don’t know where you’re going, then it doesn’t matter how strong or perfect the wind behind your sails is. They won’t take you there any time soon, if ever. That isn’t to say that all of the winds are wrong or that you’re hopeless. No wind is inherently right or wrong. Whether a given wind is right or wrong for you is completely dependent on where you’re trying to go.

To put that in other words, weight lifting is great. That being said, even if you’re super consistent and are making gains, it isn’t going to help you touch your toes. The type of practice necessary to build flexibility and to touch your toes is different from the practice you’re getting while building muscle. That doesn’t mean that strength and flexibility are incompatible or that one is more important than the other, just that they require different approaches to training.

To borrow Vince Lombardi’s quote and apply it to language:

Practice doesn’t make perfect.

Perfect practice makes perfect.

The most important lesson you can take from this post is that, whenever you’re considering adding something to your regimen, you should stop to think about what that practice is going to do for you.

Be mindful, diagnose the reasons you’re struggling, plan accordingly.

The Map: Why “I don’t understand Japanese” is not an accurate statement.

Comprehension is not a black and white matter. It’s one of grey fuzziness.

Unless you’re listening to a completely foreign language, there is no point at which “I don’t understand this” will mean “I understand absolutely 0% of this”. There will always be stuff you can pick out amidst the confusion, even if what you can pick out amounts to an empty Madlibs story, even if it’s just a です.

That in mind, rather than just binarily chalking something up to “understood” or “not understood” when you’re listening to music and following the map I’m laying out for you, I’d like you to start thinking about where and why things are a little fuzzy. By nature of being a holistic skill, more than one of the below factors might contribute fuzziness to a given piece of audio at the same time. Each time you clear up one of these “fuzzy” areas you’ll gain a bit more clarity and, eventually, tip the scales with an incomprehensible piece of audio to make it audible.

1: Pronunciation Issues: When you can’t make out それは from the chaos

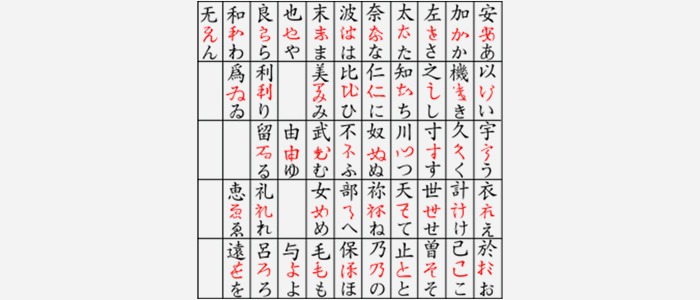

Orthography refers to the conventions that a given language employs to connect its written language to its spoken language – how it sounds to how it looks. Each language has its own orthography and, unfortunately, they often don’t completely match up. If you aren’t familiar with the orthography of Japanese, the sounds you perceive won’t always match up with the kana you see (and vice versa).

Orthography problems, then, come in two major flavors:

– Connecting sounds to kana. This means hearing so̞ɾe̞ ɰᵝa̠ and thinking それは

– Generating the right sounds from kana. This means seeing それは and knowing exactly which sounds to make. For example, you should be making the “d” sound that Americans make in the middle of better when you say れ, not the “r” sound that really begins with.

There’s a whole lot more that could be covered with pronunciation and we got into it in a bit more detail in our previous post on listening comprehension. That being said, everything you learn about pronunciation is working towards the same goal of not being surprised by what you hear and knowing what to expect. Having your ears and eyes on the same page (pun intended) will let you focus on other problem areas.

Pronunciation is knowing what sounds can exist in Japanese, and that’s the foundation upon which everything you ever do with the language rests.

A Pronunciation Solution: The International Phonetic Alphabet

130 odd years ago, linguists came up with something called the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) as a means to bring order into the chaotic realm of orthography. Each unique sound was given a unique letter, meaning that our subjectively spelled words now also had an objective representation. No more funny business like the same gh representing one sound in through, another in though and still another in tough. An IPA character like /t/ represents the same sound, a single sound, no matter what word it’s spelling or language it’s talking about.

Although it may look daunting, the IPA is one of the most important pronunciation tools that exists, and any time you spend playing with it won’t be wasted.

Bring up both the English IPA and the Japanese IPA on Wikipedia. I suggest picking an IPA character in one language and then trying to find it in the other. Doing so you’ll notice a few things:

1. English has a few sounds that Japanese doesn’t have, like the /ɹ/ in right or try – don’t make these sounds when you speak Japanese.

2. Japanese has a few sounds that English doesn’t have, like the /ɸ/ in そんな風に (そんなふうに) – “in that way/manner”. Learn these sounds.

3. Some sounds are similar but not quite the same, such as the sh sound in おいしい (/ɕ/) – delicious, and the sh sound in ship (/ʃ/). Sort these sounds out.

4. Some of the kana have more than one potential pronunciation. Compare the ぜ sound in 風(かぜ) (/z/) – wind with the one in 全然(ぜんぜん)(/dz/) – completely/not at all or the す sound in 好き( すき) (/sɯ̥/) – like with the one in すみません (/sɯ/) – excuse me. These sounds are in “free variation” and are interchangeable, so just be aware of them.

The IPA is pretty heavy stuff to get into, so if you’re struggling, YouTube has a lot of free content about Japanese pronunciation. Here’s a video that compares the sounds in English in Japanese.

Strengthening the connection between your ears and your eyes will allow you to hear anything you pick up with more clarity, reducing some of the fuzziness, which better sets you up to understand whatever it is you’re listening to.

2: Knowledge Issues: When you don’t know what それは means

Pronunciation is important, but language is much more than a mere collection of sounds. You’ll quickly find yourself running into another issue: you’re picking out the right sounds, but don’t know what those sounds mean. In my case, I even had trouble figuring out where one word ended and another began. Japanese doesn’t use any spaces, so your eyes can’t even help you here – you’ve just got to know it!

There are a few major reasons you might not be able to connect meaning to sound:

1. Vocabulary; you just haven’t learned that word yet.

2. Grammar; the relationship between the words is fuzzy.

3. Accent / Register; you haven’t experienced the different “flavors” of a given word yet.

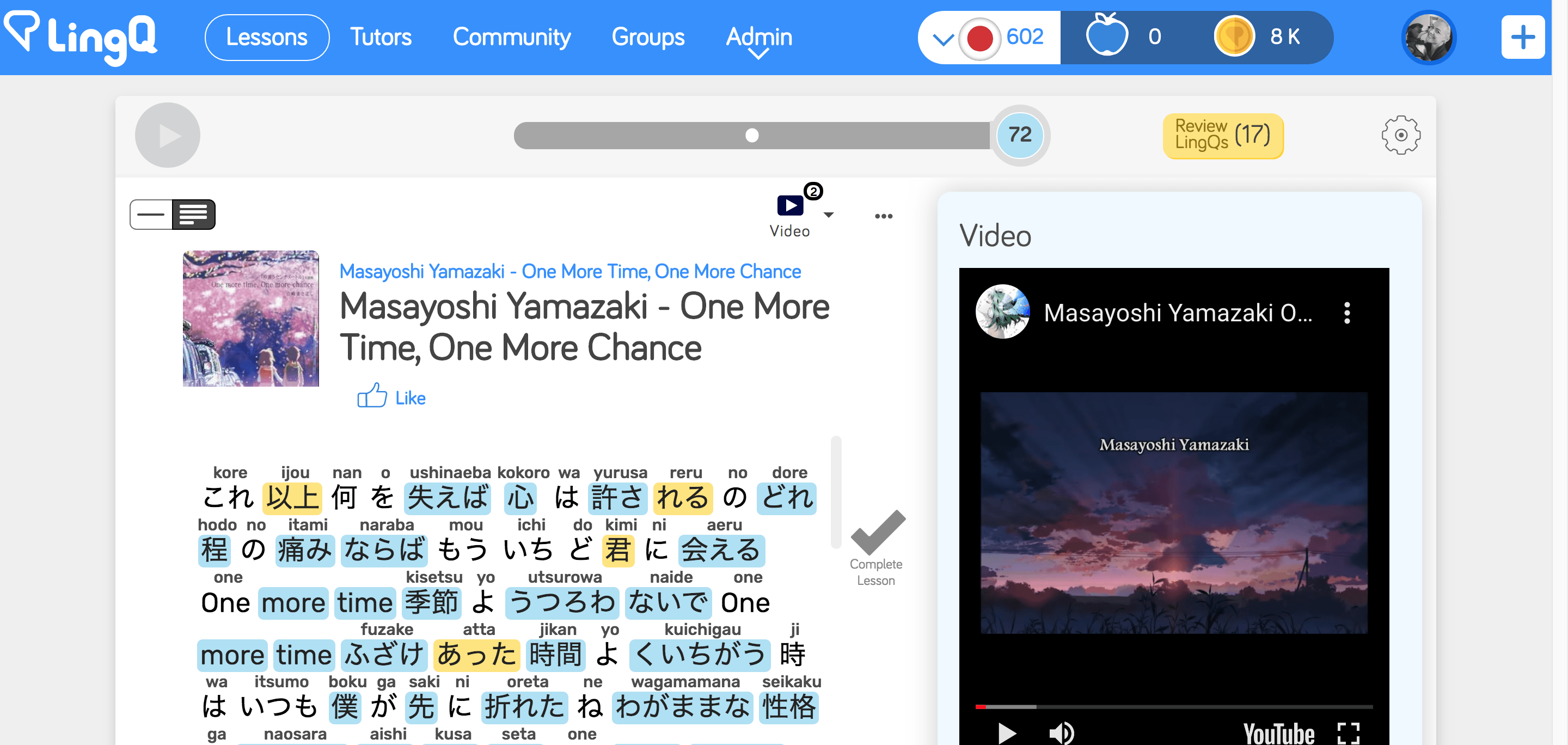

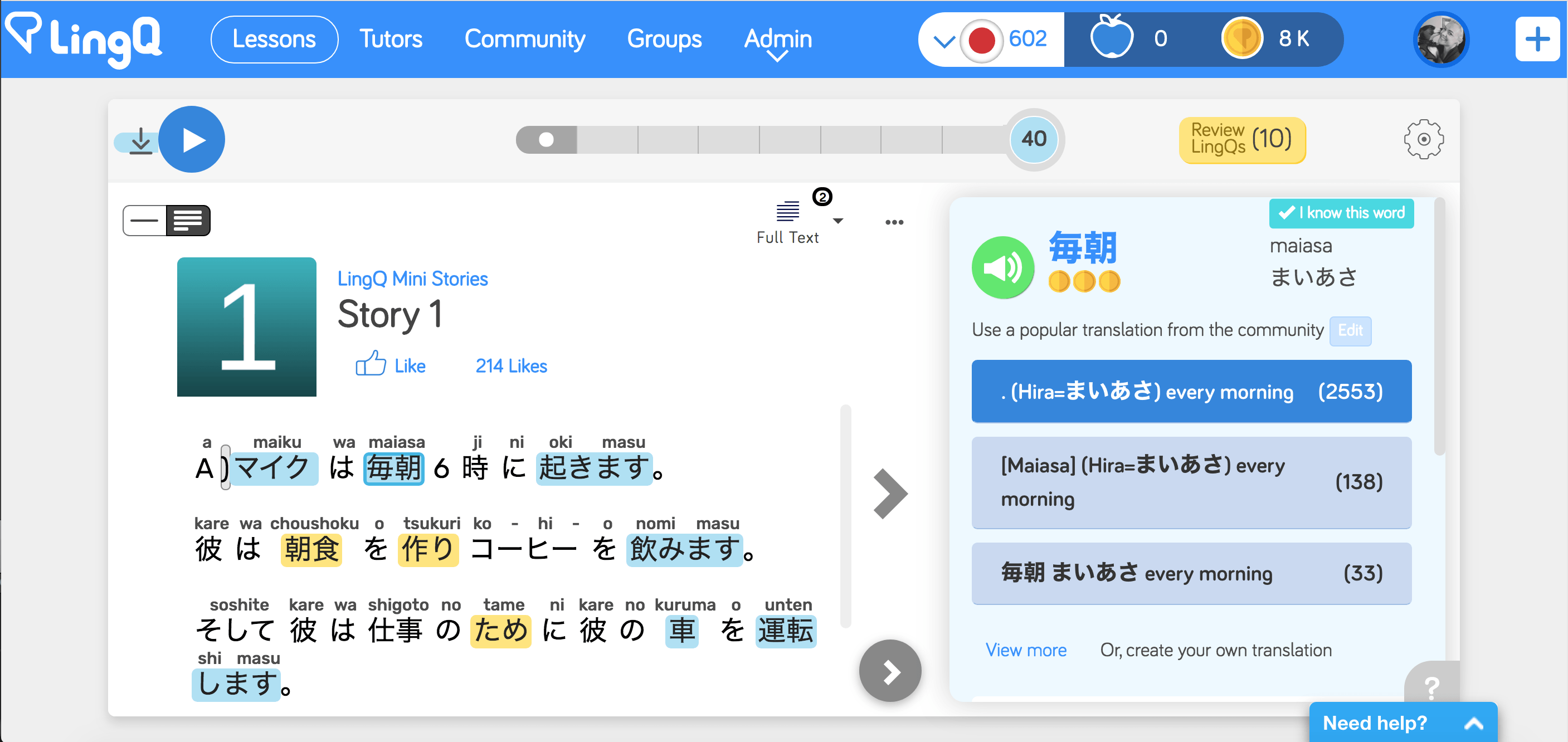

As an aside, this particular issue is why we’re here. We believe that Japanese is best learned by spending time in Japanese, but there’s a pretty significant knowledge floor required to be able to sit down and just enjoy Japanese content. That being said, modern technology helps us to work around many such issues. LingQ’s system lets you turn any YouTube video or anime into a learning resource, enabling you to get more out of the content you love – and get to it sooner!

Knowledge Solutions: Being consistent with your Japanese studies

Knowledge is, unfortunately, something you have or don’t have. Learning a language is a never ending process of filling in holes, but you can get ahead of the game by being mindful and keeping track of the holes you run into. They’ll get filled eventually.

The good news is that this is one of the few things in life where progress is basically guaranteed. In the first book I read I looked up almost 1,000 words in 300 pages, but a few dozen books later, I’m down to 167 words in a 500 page book. So long as you’re consistent and stick with it, this will get easier as you go.

1. If you don’t understand something because you’re missing keywords, go out and learn those keywords. You might use an SRS like Anki or an all-in-one software like LingQ.

2. If you know all the words in a given text but are struggling with the grammar connecting them, seek out a grammar reference. The Japanese Stack Exchange and LingQ Forum are a particularly useful resources where you can get help breaking difficult grammar structures down.

3. If you’re not sure how to break something down, just Google the entire thing. It might be an idiom or a fixed phrase.

It’s going to take time to learn all the words, kanji and grammar points that you need to know, so pick a routine and stick with it. You’ll be there before long!

3. Accent + Register Issues: When それは doesn’t sound like それは

Unfortunately, even if you were to have memorized the dictionary and had a golden ear for Japanese, you wouldn’t always be able to discern meaning out of what you heard. This is partly due to a linguistic concept called register, or how we use language differently in different circumstances, and is what people are talking about when they say “casual” vs “formal” Japanese.

In other words, sometimes a native Japanese speaker will say そりゃ when they mean to say それは, just as a native English speaker will say whatcha when they mean to say what are you. People in Okayama say さみい when people elsewhere in Japan would say さむい, just like people in the US say day but people in Australia say dye.

As a general rule of thumb, words get contracted in casual Japanese and stretched out in formal Japanese.

Accent + Register Solutions: Take it on a case-by-case basis

Register issues are ultimately knowledge problems. Even if you clearly pick out そりゃ from the jumble of phonemes (sound blocks) and know the meaning of それは, you probably won’t be able to connect the two until you’ve seen it spelled out a few times. Accent/Register issues are confusing at first, but ultimately easy fixes. After all, all you have to do is connect two pieces of already existing knowledge. That’s much easier to do than creating new pieces of knowledge. I suggest:

1. Googling “[weird contracted phrase that isn’t in your dictionary] 意味”. 意味(いみ)means meaning and will bring up Japanese explanations of the term. The first result for

“そりゃ 意味” is Goo dictionary’s entry for そりゃ, which clearly defines it as “それは”.

2. If you aren’t comfortable navigating your way around the internet in Japanese, paste the term you aren’t familiar with into the LearnJapanese subreddit. Looking up そりゃ currently yields three posts, each one connecting それは to そりゃ.

3. Reading up on casual Japanese in general – the contraction that takes place in casual speech follows pretty intuitive rules.

4. Asking about it on a platform like HiNative or HelloTalk where Japanese people studying English can help you. Somebody over there has already asked about そりゃ, too.

This ultimately all comes down to mindfulness: make a note when you don’t understand something and remember to look it up.

Pro Tip: You’ll get more bang for your buck by consuming content that’s both limited and consistent in its language style. An easy way to do this is by picking a single Japanese Youtuber you like and focusing on their stuff. You’ll quickly get used to the quirks of their speech and have a much easier time understanding them than a random person.

In other words, if you get used to macho Tokyo Japanese, you’re going to have a much easier time understanding another person speaking macho Tokyo Japanese than you will a Kansai grandma or a 16 year old girl’s Japanese, even if she’s also from Tokyo.

4. Processing Problems: Your brain can’t keep up with what you’re hearing

Have you ever had a moment where you knew every single vocabulary word and grammar point that came up in a dialogue from an anime or drama but, somehow, came up blank without much of an idea what just happened? I call this a processing problem. A processing problem means that all the necessary knowledge is already inside your brain, it just isn’t being strung together efficiently or quickly enough to follow a given dialogue.

I think a big part of processing problems amount to familiarity or intimacy with the language. You’ll likely find yourself in an odd flux with some content where you can understand it in some circumstances but struggle with it in others.

For example, I really like a motivational speaker named Yoshihito Kamogashira. I normally find his content pretty easy to follow and I really like his voice, so I’ve adopted him as my “Japanese parent” and shadow one of his videos each day while walking to the subway.

That being said, I pretty much only listen to his content during this time of day: it’s a golden 20 minutes where I’m full of energy and definitely won’t be bothered. I get much less out of his videos when I’m tired and constantly distracted on a noisy subway.

Pro-tip: Figure out when you’re at your best each day and do the work most important to you during this time. I’m personally self-conscious about my Japanese accent, so I spend this time working specifically on pronunciation.

Processing Solutions: Practice (sometimes) makes perfect

Issues with processing are where the phrase “practice makes perfect” really applies to language learning: you’ve got all your knowledge bases covered, you just need to get quicker at moving between them.

You’ll naturally get better at processing Japanese – understanding it more reliably and more quickly – just by consuming more of it and slowly ironing out your understanding of Japanese grammar/culture. Find content you enjoy, stick with it, and things will naturally begin falling in place.

For now, you can give yourself a head-start by doing two things:

1. Shrink the size of the content you’re consuming. There is much less unique Japanese in a 30 second clip than a 30 minute video.

2. Listen to the content more than once. You’ll pick up more and more each time and, after awhile, be able to follow it practically in your sleep.

I personally recommend falling in love with a Japanese band, but clips from a YouTuber you enjoy (or really anything) work just fine, too. I’ll get into the details on that down below.

5. Comprehension Problems: Not following what それは is referring to

Each language is easier in some ways and more difficult in others. One of the particularly difficult aspects of Japanese for me as a native English speaker is that Japan is a high-context culture, basically meaning that a Japanese person will often use less words to communicate a given piece of information and do so more indirectly than somebody from the US or England would.

It also means that subjects and topics tend to flow much more freely and need less explicit clarification than would be expected in a given English text, so you’ve really got to pay attention to the dots are and how they’re connected. If something seems to come out of nowhere, chances are that dots got connected earlier without you realizing.

This is really difficult – it isn’t some concrete skill you can dutifully tread through like vocabulary or JLPT grammar points. It’s more a mindset about how communication should take place, and it takes time to adjust to.

Comprehension Solutions: Break it down & seek help

In my opinion, the best way to approach comprehension is to approach it last. The more “fuzz” you can eliminate, the better chance you’ll have at reading between the lines. That in mind, if you’re listening to something and suddenly find yourself confused because you aren’t sure what happened between point A and point B, go back and work through the other skills first.

1. Make sure you’re hearing the audio as clear as can be – that there aren’t any sound bits that you can’t make out. If you can’t pick a few words or sentences out, work on them. They might contain information you need to understand the point being made.

2. After you’re hearing things clearly or have found a transcript, plug it into LingQ to iron out your knowledge hurdles. Look up new words, check on confusing grammar and make sense of any grey areas caused by accent/register.

3. Listen to your clip a few times so that your brain has ample time to catch up and process it. You’ll pick up information you missed with each pass and that’ll often be enough to make sense of what at first seemed like an enigma.

4. There will, of course, be times when you’re really stumped. Hunt down a translation of the material and go line by line. Look for information or nuance that clears things up, and once you find it, take a moment to think about why you weren’t picking up on it in Japanese.

5. If you’re still getting nowhere even with a translation, ask other learners on Reddit/Stack Exchange, ask Japanese people on HiNative/HelloTalk or consider going over the content with a tutor on iTalki.

Reading: The Super-Power behind Listening Comprehension

Odd as it might seem, reading more is one of the most important steps you can take towards improving your listening comprehension. If you can’t follow an idea when it’s clearly spelled out in front of you, you definitely won’t catch it on the fly out of somebody’s mouth. Take time to read stuff you enjoy on LingQ or by working through simple content online – you’ll learn tons of vocabulary, be exposed to lots of grammar and internalize how information gets communicated in Japanese.

I also really recommend looking into reading comprehension books for your JLPT level like the ones by Kanzen Master, Sou Matome, Drill & Drill, Try! or Jitsuryoku Appu. Reading comprehension books are great because they walk through each answer, explaining why it is or isn’t right. That sort of feedback is critical for reaching an advanced level of fluency.

I think that this sort of practice goes a long ways towards understanding how ideas are constructed and conveyed in Japanese. Once you’ve built those comprehension pathways with your eyes (reading) you can start picking up on them with your ears (listening), too.

Why music is the perfect place to start improving your listening comprehension

I’m a big believer in using a language that I’m learning as soon as possible rather than eternally preparing to use it and I also crave tangible results. Even if I understand that something I’m learning will be important later, I get discouraged if I can’t see some fruits from my learning right away. The goal of all my learning, then, is to establish a greater connection between the language and myself. Music helps do this in a few ways:

– Songs are very short compared to other types of media which makes them very accessible. Even day 1 learners can make tangible progress through a given song and feel like they’re getting somewhere. This keeps learning fresh and exciting.

– Songs are, in essence, compilations of power phrases and expressions. They just don’t have the space to accommodate expansive details and storylines, meaning that every single line is powerful and probably contains a grammar idea you can repurpose for yourself.

– If we like a song, we’re definitely going to listen to it more than once. This is great news as a learner! How many times have you learned some new grammar point in class only to fumble around with it on the tip of your tongue in a conversation or find yourself unsure how exactly to use it on a test? Getting repeated exposure to these structures will help to get them into your memory and out of your mouth.

In Practice: How to learn Japanese with music

The first step, naturally, is finding a band or artist that you enjoy and want to invest a bit of effort into understanding better. I don’t know what type of music you like, so I’m going to build this section of the post around Masayoshi Yamazaki’s superhit, One More Time, One More Chance.

That being said, I put together a huge list of musicians from multiple genres in the post when I talked about why I learned Japanese, so if Masayoshi’s style isn’t for you, take a peek over there. I’ve included a wide variety of artists that span everything from rap to rock, oldies to pop.

Step 1: Approach this with a discovery-oriented mindset.

Before I even get started, I want to establish a very important point. This is not like listening to something in your native language – we won’t just be absent-mindedly listening nor listening purely for entertainment. This is not a passive activity. You’re also going to have trouble with it.

I think that it’s sort of like playing Minesweeper. You know there are mines all over (stuff you don’t understand) and your goal is to figure out where they are, isolate them and then deal with them. This sort of listening is basically a more entertaining means of exposing yourself to new stuff to learn than a textbook and a less daunting means of learning grammar than working through a JLPT list.

You’re basically doing three things over and over again through a variety of contexts:

1. Asking yourself, “What is here that I don’t understand?” (find the mines)

2. Asking yourself, “Why do I not understand what’s going on here?” (isolate them)

3. Researching to clear up any fuzziness pertaining to 1 + 2. (deal with them)

In other words, we’re going into this expecting not to be able to cruise to the end of the song. You know that you’re going to run into a wall (and a lot of them), it’s more about patiently working through the song and expecting to learn a lot along the way. If you don’t understand everything you hear at first, or even after multiple listens, that’s perfectly normal.

Step 2: Pay attention to your band’s pronunciation

I earlier asked you to take a discovery oriented mindset, not a stoic or hard-working one. I’m not going to ask you to do something crazy like transcribe an entire song into IPA symbols. For now, I’d like to put more emphasis on the pay attention bit than the pronunciation one. Just sit, listen to the music, pay attention to how Masayoshi sings and see what you notice.

You’re bound to stumble onto some interesting stuff. For example, in Masayoshi’s One More Time, One More Chance:

– You might notice how his Japanese accent comes out when he sings in English. Listen carefully to how he says “One more time” at :30. What do you notice? Does this give you any information you should keep in mind for when you speak Japanese?

– Pay attention to his articulation of morae (Japanese syllables, basically) – especially at at 4:23, where he picks up the tempo a bit. Is each syllable (mora) clear and independent from the rest? Does he start slurring them together, like how part of this becomes par’da dis when we speak quickly? Do other Japanese people articulate like that? What about when people speak really fast, like Yoneze Kenshi singing Loser or Wednesday Campanella singing Shakushain?

– Listen carefully to how he says へ at 3:42. Now say the (English) word hey. Now say it very, very slowly – over the course of 5 full seconds. Really drag it out. What do you notice about the ending of your hey and the ending of his へ? Here’s another recording of へ‘s pronunciation, just in case he sings too fast.

Again, this is all about discovery. You don’t have to memorize any of this or even understand why it happens right now – what’s more important is that you notice stuff, be loosely aware that it exists and continue to listen for it. Trust your ears. You’ll get a more concrete grasp of these patterns as you listen more.

Again, this is all about discovery. You don’t have to memorize any of this or even understand why it happens right now – what’s more important is that you notice stuff, be loosely aware that it exists and continue to listen for it. Trust your ears. You’ll get a more concrete grasp of these patterns as you listen more.

This awareness is a really important part of listening comprehension. It helps to prevent you from getting surprised and confused when something unexpected happens – whether that’s not hearing a sound you were expecting to hear, or hearing one that you didn’t expect to hear.

That being said, awareness isn’t everything. I adore a French singer named Meitre Gims and can rap along with several of his songs, but I’ve got no idea what he’s saying. Like, I literally broke some songs down in Audacity and took them syllable by syllable. But I still don’t speak or understand French. At all. The things you notice while listening will only be useful if you take the next steps of learning what they are, figuring them out and applying them.

Step 3: Iron out the knowledge issues

You’ll be listening to these songs more than once, so feel free to chip away at them over time. Again, you don’t have to literally deconstruct the entire song. Look up unknown words, try to figure out new grammar points, and then focus on remembering the stuff that seems useful or that you could see yourself using in your next conversation.

More than anything, you should be scanning the song for conversational connectors and “power phrases” that you can take and use for yourself. For example:

– もういちど at :27 means “one more time” and you can just drop it in front of any verb/verb phrase. If you don’t understand what somebody says, you might say もういちど言ってください(もういちどいってください) to ask them to repeat themselves. Please say (that) one more time.

– 先に (さきに) at :51 means “to do something first/before someone else” and is in a lot of fixed phrases, like 先にどうぞ, after you, or 先に失礼します, a phrase you say when you’re leaving (work/an event/etc) early/before your colleagues.

– 今すぐ (いますぐ) at 1:34 means “right away/from right now”, and you can just tack any word you want onto the end of it to say what you’ll do – I’m going right now / I’ll go right away would just be 今すぐ行きます.

These are all important phrases that could come up in any conversation, so they’ll give you the biggest short-term bang for your buck.

If you’re feeling especially productive or are working with a tutor, you might break some of the grammar down in further detail. This song features a lot of verbs that end in ば or get used with the word なら – but what does that mean? The chorus includes the phrase はずもない, but what is はず? What’s the difference between はずもない and はずがない?

Accent/register issues are also knowledge issues, so to wrap the section up, take a bit to think about what どっかに at 4:26 could possibly mean. If you can’t figure out, don’t fret. Somebody has probably already been confused about it – just like this person on HiNative.

Step 4: Bring out your inner karaoke star

Step four is a fun place to be at! At this point you understand the song, or at least parts of the song, and you’ve also got a couple ideas of pronunciation stuff to keep an eye… ear out for. Now it’s time to start producing. The fact that you can understand a song doesn’t necessarily guarantee that you can sing along with it.

While your chops will get a big workout during this phase, this isn’t only about mouth work. It’s a consolidation phase for everything. All the singing practice also helps strengthen the connection from brain to mouth, ensuring that you’ll feel more comfortable and natural using your Japanese when the time comes. If you don’t believe me, try listening to いいんですか? by Radwimps literally just twice and then observe how beautifully いいんですか? Begins flowing from your lips. I dare say you will become physically incapable of saying it wrong.

You can make things a bit more efficient by choosing which songs you learn based on the grammar points contained in them. Here’s a small compilation of examples:

– Again, practice ~ば form with One More Time, One More Chance by Yamazaki Masayoshi.

– Practice polite questions with 明日への手紙 (あすへのてがみ)by Aoi Teshima

– Practice the て form of with 穴を掘っている (あなをほっている) by Amazarashi

– Practice a ton of rough/casual forms with RGTO by AKLO

– Practice the past tense with 春愁 (しゅんしゅう) by Mrs. Green Apple

Whether they’re big grammar points or just small phrases and keywords, the time you spend enjoying and singing the song will be an exercise for your brain just as much as your mouth. On top of all of that, you’ll get a huge burst of confidence once you master a song and are able to sing along for the first time.

This is the point where Japanese stops being a foreign language and starts becoming part of you and your life.

Step 5: Get help breaking down the stuff you can’t figure out

Even after you’ve looked up every word and grammar point in the entire song, there will still likely be stuff that confuses you a bit. Compile these bigger questions and ask a teacher, tutor or friend.

It might be smaller stuff – you get the difference between ならば and なら, but can’t quite put your finger on how it feels different to use each one. Why do both of these words exist? What’s the nuance behind each one? Why does he say ならば here instead of なら?

On the other hand, you might have to deal with slightly bigger comprehension issues that involve some mental gymnastics or metaphors. The use of language in music is much more liberal than speech, so you’ll encounter much more poetic phrasing that you wouldn’t normally hear in everyday life. Here’s a phrase from the song that personally threw me off the first time I heard the song.

いつでも捜しているよ (いつでもさがしているよ)

I’m always looking, searchingどっかに君の姿を (きみのすがたを)

For a glimpse of you, somewhere交差点でも 夢の中でも(こうさてんでも ゆめのなかでも)

Even at intersections and in my dreamsこんなとこにいるはずもないのに

Even though I know you won’t be there

(lit: even though there’s no reason you’d be in places like these)

I was confused because I had never seen an object (the thing that comes before を) being put after a verb before – my textbooks had said that objects come before verbs in Japanese. It turns out that this inversion is actually quite common, especially in casual speech, so I probably would have stumbled into it if I spent more time out and about than with my textbook. My point is that everybody has a different background with Japanese, so there are no dumb questions – figure stuff out as you run into it.

Step 6: Slowly build your repertoire of music

Japanese music was weird for me in that it took forever to get into – I spent almost two years lamenting the fact that I just didn’t care for Japanese music. Then, out of the blue, I stumbled onto アイネクライネ by Yonezu Kenshi and was instantly hooked. I went through his entire repertoire and along the way stumbled onto The Reason I Thought I’d Die by Amazarashi and found myself in love again.. And from that point, I never had trouble finding music I liked.

Every song you work through has new things to learn, new phonetic patterns to practice and different points to appreciate. Each singer has a different accent and tone, may employ one of several registers and make different word choices. You’ll expose yourself to and become comfortable with a ton of Japanese voices just by working through more and more music. Best of all, songs are shorter-term projects even if you’re a beginner.

Take some time to look around and find a song you really like, click through the recommended videos/similar artists and fill out your niche. The most important part of this is that you don’t need to be an advanced learned to start building a connection to the language.

Wrapping Up

The Japanese language is huge, so divide and conquer. You’re much closer to understanding the dialogue contained in any given piece of Japanese media – be it a Japanese dictionary entry, a song, a YouTube vlog, drama or video – than you are to understanding Japanese. Use this to your advantage: Take small bits of Japanese that you enjoy and figure them out.

The more “chunks” of content you consume, the faster you’ll get at working through them and the more familiar you’ll get with how Japanese sounds. As you go you’ll gradually become able to deal with bigger and bigger chunks – eventually you’ll just hear stuff and it’ll bear meaning without you having to think about it.

Before long, you might find yourself ready to explore something else. There’s a ton of cool stuff in Japanese beyond music, and you can apply these same steps to breaking down any piece of content that you’re working with. LingQ is the best way to learn Japanese online because it lets you learn from content you enjoy!

If you hope to read light novels one day, try out LingQ’s Mini Stories in Japanese. They’re just that – 60 easy stories, aimed at beginners, entirely in Japanese – and available for free.

If you’re excited about Japanese dramas and anime, start out by subscribing to a few Japanese YouTube channels – many come with subtitles and will help you get used to what normal Japanese speech sounds like.

Enjoyed this post? Check out polyglot and LingQ cofounder Steve Kaufmann’s YouTube video for some tips for learning Japanese!

If you feel a bit lost, try working through Minna no Nihongo on YouTube to build a foundation first.

***

Sami is a bookworm who got taken to Japan 5 years ago by a dart and a globe. He has since lived in Russia and Taiwan, but Japanese has continued to be a big part of his life.