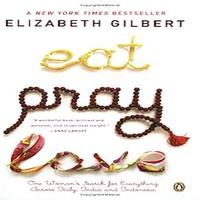

Eat Pray Love ch 15

The interesting thing about my Italian class is that nobody really needs to be there. There are twelve of us studying together, of all ages, from all over the world, and everybody has come to Rome for the same reason—to study Italian just because they feel like it. Not one of us can identify a single practical reason for being here. Nobody's boss has said to anyone, “It is vital that you learn to speak Italian in order for us to conduct our business overseas.” Everybody, even the uptight German engineer, shares what I thought was my own personal motive: we all want to speak Italian because we love the way it makes us feel. A sad-faced Russian woman tells us she's treating herself to Italian lessons because “I think I deserve something beautiful.” The German engineer says, “I want Italian because I love the dolce vita”—the sweet life. (Only, in his stiff Germanic accent, it ends up sounding like he said he loved “the deutsche vita”—the German life—which I'm afraid he's already had plenty of.) As I will find out over the next few months, there are actually some good reasons that Italian is the most seductively beautiful language in the world, and why I'm not the only person who thinks so. To understand why, you have to first understand that Europe was once a pandemonium of numberless Latin-derived dialects that gradually, over the centuries, morphed into a few separate languages—French, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian. What happened in France, Portugal and Spain was an organic evolution: the dialect of the most prominent city gradually became the accepted language of the whole region. Therefore, what we today call French is really a version of medieval Parisian. Portuguese is really Lisboan. Spanish is essentially Madrileño. These were capitalist victories; the strongest city ultimately determined the language of the whole country. Italy was different. One critical difference was that, for the longest time, Italy wasn't even a country. It didn't get itself unified until quite late in life (1861) and until then was a peninsula of warring city-states dominated by proud local princes or other European powers. Parts of Italy belonged to France, parts to Spain, parts to the Church, parts to whoever could grab the local fortress or palace. The Italian people were alternatively humiliated and cavalier about all this domination. Most didn't much like being colonized by their fellow Europeans, but there was always that apathetic crowd that said, “Franza o Spagna, purchè se magna,” which means, in dialect, “France or Spain, as long as I can eat.”

All this internal division meant that Italy never properly coalesced, and Italian didn't either. So it's not surprising that, for centuries, Italians wrote and spoke in local dialects that were mutually unfathomable. A scientist in Florence could barely communicate with a poet in Sicily or a merchant in Venice (except in Latin, of course, which was hardly considered the national language). In the sixteenth century, some Italian intellectuals got together and decided that this was absurd. This Italian peninsula needed an Italian language, at least in the written form, which everyone could agree upon. So this gathering of intellectuals proceeded to do something unprecedented in the history of Europe; they handpicked the most beautiful of all the local dialects and crowned it Italian. In order to find the most beautiful dialect ever spoken in Italy, they had to reach back in time two hundred years to fourteenth-century Florence. What this congress decided would henceforth be considered proper Italian was the personal language of the great Florentine poet Dante Alighieri. When Dante published his Divine Comedy back in 1321, detailing a visionary progression through Hell, Purgatory and Heaven, he'd shocked the literate world by not writing in Latin. He felt that Latin was a corrupted, elitist language, and that the use of it in serious prose had “turned literature into a harlot” by making universal narrative into something that could only be bought with money, through the privilege of an aristocratic education. Instead, Dante turned back to the streets, picking up the real Florentine language spoken by the residents of his city (who included such luminous contemporaries as Boccaccio and Petrarch) and using that language to tell his tale. He wrote his masterpiece in what he called dolce stil nuovo, the “sweet new style” of the vernacular, and he shaped that vernacular even as he was writing it, affecting it as personally as Shakespeare would someday affect Elizabethan English. For a group of nationalist intellectuals much later in history to have sat down and decided that Dante's Italian would now be the official language of Italy would be very much as if a group of Oxford dons had sat down one day in the early nineteenth century and decided that—from this point forward—everybody in England was going to speak pure Shakespeare. And it actually worked. The Italian we speak today, therefore, is not Roman or Venetian (though these were the powerful military and merchant cities) nor even really entirely Florentine. Essentially, it is Dantean. No other European language has such an artistic pedigree. And perhaps no language was ever more perfectly ordained to express human emotions than this fourteenth-century Florentine Italian, as embellished by one of Western civilization's greatest poets. Dante wrote his Divine Comedy in terza rima, triple rhyme, a chain of rhymes with each rhyme repeating three times every five lines, giving his pretty Florentine vernacular what scholars call “a cascading rhythm”—a rhythm which still lives in the tumbling, poetic cadences spoken by Italian cabdrivers and butchers and government administrators even today. The last line of the Divine Comedy, in which Dante is faced with the vision of God Himself, is a sentiment that is still easily understandable by anyone familiar with so-called modern Italian. Dante writes that God is not merely a blinding vision of glorious light, but that He is, most of all, l'amor che move il sole e l'altre stelle . “The love that moves the sun and the other stars.” So it's really no wonder that I want so desperately to learn this language.