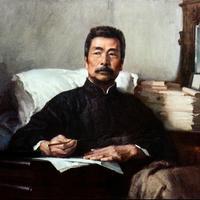

#41: 鲁迅和他笔下的人

Lỗ Tấn và nhân vật

Lu Xun et les personnages de sa plume

Lu Xun and the people in his writing

Лу Сінь та його персонажі

#Nr. 41: Lu Xun und die Menschen, über die er geschrieben hat

#41: Ο Lu Xun και οι άνθρωποι για τους οποίους έγραψε

#41: Lu Xun and his people

#41: Lu Xun y la gente sobre la que escribió

#41 : Lu Xun et les personnes sur lesquelles il a écrit

#41: Lu Xun e le persone di cui scriveva

#第41回:魯迅とその作品に登場する人々

#41: Lu Xun e as pessoas sobre quem escreveu

英国 的 读者 GavinBanks 让 我 介绍 中国 文学 , 我 首先 想到 的 就是 鲁迅 。

the UK||Reader|Gavin Banks|||introduce||literature||first|think of||is|Lu Xun

||читач|Гевін Бенкс|||||||||||

Der britische Leser GavinBanks bat mich, chinesische Literatur vorzustellen. Das erste, woran ich dachte, war Lu Xun.

British reader GavinBanks asked me to introduce Chinese literature. The first thing I thought of was Lu Xun.

Gavin Banks, un lector del Reino Unido, me pidió que presentara la literatura china y lo primero en lo que pensé fue en Lu Xun.

Lorsque Gavin Banks, un lecteur du Royaume-Uni, m'a demandé de présenter la littérature chinoise, la première chose qui m'est venue à l'esprit a été Lu Xun.

イギリスの読者GavinBanksは私に中国文学を紹介するように頼んできたので、最初に思い浮かんだのは魯迅です。

Gavin Banks, um leitor do Reino Unido, pediu-me que apresentasse a literatura chinesa e a primeira coisa em que pensei foi em Lu Xun.

很多年 来 , 鲁迅 的 作品 一直 出现 在 中国 学生 的 教科书 上 。

||||œuvre|||||||manuel scolaire|

many years|for many years|Lu Xun||works|has always|appeared|||||textbooks|

Seit vielen Jahren erscheinen Lu Xuns Werke in Lehrbüchern chinesischer Studenten.

For many years, Lu Xun's work has always appeared in Chinese students' textbooks.

Durante muchos años, las obras de Lu Xun han aparecido en los libros de texto de los estudiantes chinos.

Depuis de nombreuses années, les œuvres de Lu Xun figurent dans les manuels scolaires des étudiants chinois.

何年もの間、魯迅の作品は中国の学生の教科書にずっと登場しています。

鲁迅 在 中国 几乎 无人不知 、 无人不晓 。

||||personne ne connaît|sait

Lu Xun|||almost everyone|everyone knows|everyone knows

Lu Xun ist in China so gut wie jedem bekannt.

Lu Xun is almost known by everyone in China.

Lu Xun es conocido por casi todo el mundo en China.

Lu Xun est connu de presque tous les Chinois.

魯迅は中国ではほぼ誰もが知っており、無名無知の存在です。

Lu Xun é conhecido por quase toda a gente na China.

鲁迅 的 真 名 叫 周树人 , 鲁迅 是 他 的 笔名 。

|||||Chu Thụ Nhân|||||Bút danh

|||nom||Zhou Shuren|||||

Lu Xun||real|name|is called|Zhou Shuren|Lu Xun||||pen name

Der richtige Name von Lu Xun ist Zhou Shuren, Lu Xun ist sein Pseudonym.

Lu Xun's real name is Zhou Shuren, Lu Xun is his pen name.

El verdadero nombre de Lu Xun era Zhou Shuren, y Lu Xun era su seudónimo.

O nome verdadeiro de Lu Xun era Zhou Shuren, e Lu Xun era o seu pseudónimo.

鲁迅 生于 1881 年 的 浙江 绍兴 。

|est né|||Zhejiang|Shaoxing

Lu Xun|born in|||Zhejiang|Shaoxing

Lu Xun wurde 1881 in Shaoxing, Zhejiang, geboren.

Lu Xun was born in 1881 in Shaoxing, Zhejiang.

Lu Xun nació en 1881 en Shaoxing, provincia de Zhejiang.

魯迅は1881年に浙江省紹興で生まれた。

Lu Xun nasceu em 1881 em Shaoxing, província de Zhejiang.

十九 世纪末 , 中国 社会 非常 混乱 : 西方 帝国 入侵 , 清政府 渐渐 走向 灭亡 , 人们 希望 实现 民主 。

||||||||||||sụp đổ||||

dix-neuf|fin de siècle||société||chaotique||empire|invasion||graduellement|se dirigeait vers|mort|||réaliser|démocratie

Nineteenth century|the end of the 19th century||society||chaotic|the West|empire|invasion|Qing government|gradually|is heading towards|to perish||hope|to achieve|democracy

Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts war die chinesische Gesellschaft sehr chaotisch: Westliche Reiche fielen ein, die Qing-Regierung starb allmählich aus und die Menschen wollten Demokratie erreichen.

At the end of the 19th century, Chinese society was in great chaos: Western empires invaded, the Qing government was gradually declining, and people hoped to achieve democracy.

A finales del siglo XIX, la sociedad china estaba sumida en la confusión: los imperios occidentales invadían el país, el gobierno Qing se arruinaba y la gente quería democracia.

À la fin du XIXe siècle, la société chinoise est en plein bouleversement : l'empire occidental a envahi le pays, le gouvernement des Qing est en voie d'extinction et la population aspire à la démocratie.

19世紀末、中国社会は非常に混乱していました:西洋の帝国が侵略し、清政府は徐々に滅亡の道をたどり、人々は民主主義を実現したいと望んでいました。

No final do século XIX, a sociedade chinesa estava a viver um período conturbado: os impérios ocidentais estavam a invadir, o governo Qing estava a cair em ruínas e as pessoas queriam democracia.

年轻 的 鲁迅 喜欢 新 事物 , 充满 了 怀疑 精神 。

||||||||hoài nghi|

||Lu Xun|||choses|est rempli||doute|esprit

young||Lu Xun||new|new things|is full of||doubt|spirit

Der junge Lu Xun mag neue Dinge und ist voller Skepsis.

A young Lu Xun likes new things and is full of a spirit of skepticism.

Al joven Lu Xun le gustaban las cosas nuevas y estaba lleno de escepticismo.

Le jeune Lu Xun aimait la nouveauté et était plein de scepticisme.

若い頃の魯迅は新しいものが好きで、疑念に満ちていました。

他 父亲 去世 的 时候 , 鲁迅 对 中医 产生 了 严重 的 怀疑 。

|||||||médecine traditionnelle chinoise|a eu||||doute

|father|passed away||when|Lu Xun||Traditional Chinese Medicine|to have serious doubts about||serious||doubt

Als sein Vater starb, hatte Lu Xun ernsthafte Zweifel an der chinesischen Medizin.

When his father passed away, Lu Xun developed serious doubts about traditional Chinese medicine.

A la muerte de su padre, Lu Xun tenía serias dudas sobre la medicina china.

À la mort de son père, Lu Xun a eu de sérieux doutes sur la médecine chinoise.

父親が亡くなった時、魯迅は伝統中国医学に重大な疑念を抱きました。

Na altura da morte do seu pai, Lu Xun tinha sérias dúvidas sobre a medicina chinesa.

于是 , 他 去 日本 学习 现代医学 , 希望 用 自己 的 双手 治病救人 。

|||||||||||chữa bệnh cứu người

|||||médecine moderne|||||mains|traiter les maladies et sauver des vies

then|||||modern medicine|hope||||hands|curing diseases and saving people

|||||||||||лікувати хвороби та рятувати людей

Also ging er nach Japan, um moderne Medizin zu studieren, in der Hoffnung, mit seinen Händen Krankheiten zu behandeln und Menschen zu retten.

Therefore, he went to Japan to study modern medicine, hoping to use his own hands to heal the sick and save lives.

Así que se fue a Japón a estudiar medicina moderna, con la esperanza de utilizar sus manos para curar a los enfermos y salvar vidas.

Il s'est donc rendu au Japon pour étudier la médecine moderne, dans l'espoir d'utiliser ses mains pour soigner les malades et sauver des vies.

そこで、自分の手で病気を治し、命を救いたいと思い、日本に留学して現代医学を学びました。

有 一次 , 他 观看 一部 关于 日俄战争 的 纪录片 。

|||a regardé|||guerre russo-japonaise||documentaire

|once||to watch|a film|about|Russo-Japanese War||documentary

Einmal sah er einen Dokumentarfilm über den russisch-japanischen Krieg.

Once he watched a documentary about the Russo-Japanese War.

Un jour, il a regardé un documentaire sur la guerre russo-japonaise.

あるとき、日露戦争のドキュメンタリーを見たそうです。

中国 人 给 俄国人 做 侦探 , 要 被 日军 枪毙 , 却 有 一群 中国 人 在 旁边 观看 。

|||||Thám tử||||||||||||

|||||détective|||armée japonaise|exécuter|mais||un groupe|||||regarder

||to give|Russian people|acting as|detective|to be|passive marker|Japanese army|be executed by firing squad|but|there is|a group|China|||beside|to watch

|||росіянин||детектив|||||||||||поруч|дивитися

Die Chinesen arbeiteten als Späher für die Russen und sollten von den Japanern erschossen werden, aber eine Gruppe von Chinesen beobachtete sie.

A Chinese person was acting as a detective for the Russians, about to be shot by the Japanese, but there was a group of Chinese people watching nearby.

Los chinos trabajaban como detectives para los rusos y fueron fusilados por los japoneses mientras un grupo de chinos observaba.

Les Chinois travaillaient comme éclaireurs pour les Russes et allaient être abattus par les Japonais, mais un groupe de Chinois les observait.

中国人はロシア人の探偵として働いていたが、中国人の集団が見守る中、日本人に銃殺された。

当时 , 在场 的 日本 人 都 欢呼 “ 万岁 ”。

|présent|||||ont acclamé|longue vie

At that time|present Japanese people||Japan|||cheer|long live

|||||||багато років

Zu diesem Zeitpunkt jubelten alle anwesenden Japaner "Hurra!

At that time, the Japanese present were all cheering 'Long live.'

En ese momento, los japoneses del público gritaron "hurra".

À ce moment-là, tous les Japonais présents ont applaudi "Hourra !

その時、会場にいた日本人から「万歳」の歓声が上がった。

Nessa altura, os japoneses na plateia aplaudiram "Hurra".

就 在 这个 时候 , 鲁迅 改变 了 自己 的 想法 , 决定 用 文学 改变 中国 人 的 思想 。

|||||||||||||||||pensée

at that time|||at that moment|Lu Xun|changed||||thought|decided||literature|change||||thought

Zu diesem Zeitpunkt änderte Lu Xun seine Meinung und beschloss, die Literatur zu nutzen, um die Chinesen umzustimmen.

It was at this moment that Lu Xun changed his mind and decided to use literature to change the thinking of the Chinese people.

この時、魯迅は心を入れ替え、文学で中国人の考え方を変えようと決意したのです。

Foi nessa altura que Lu Xun mudou de ideias e decidiu utilizar a literatura para mudar o pensamento do povo chinês.

1918 年 , 鲁迅 发表 了 小说 《 狂人日记 》。

|||||Le Journal d'un fou (1)

|Lu Xun|published||novel|The Diary of a Madman

Im Jahr 1918 veröffentlichte Lu Xun den Roman Tagebuch eines Verrückten.

In 1918, Lu Xun published the novel The Madman's Diary.

En 1918, Lu Xun a publié le roman Journal d'un fou.

1918年、魯迅は小説『狂人日記』を発表した。

Em 1918, Lu Xun publicou o seu romance Diário de um Louco.

小说 很 短 , 是 十三篇 日记 。

|||||journal

novel|very|short||thirteen entries|diary

Der Roman ist sehr kurz und besteht aus dreizehn Tagebucheinträgen.

The novel is short and is a thirteen diary.

Le roman est très court et se compose de treize entrées de journal.

この小説は、13の日記という非常に短いものです。

O romance é muito curto, treze entradas de diário.

小说 主角 发现 身边 的 人 都 在 “ 吃人 ”, 他 很 害怕 , 结果 被 人 当成 了 疯子 。

||||||||ăn thịt người|||||||||kẻ điên

|le protagoniste||autour de lui|||||manger des gens|||||||considéré||fou

novel|protagonist|discovered|around him|||all||eating people|||is afraid|result|by|people|regarded as|past tense marker|madman

||||||||їсти людей|||||||||

Der Protagonist des Romans entdeckt, dass alle um ihn herum "kannibalisch" sind, und ist so verängstigt, dass er für einen Verrückten gehalten wird.

In the novel, the protagonist discovered that everyone around him was 'eating people', he was very scared, and as a result, he was mistaken for a madman.

El protagonista de la novela descubre que todo el mundo a su alrededor está "comiendo gente" y se asusta tanto que le tachan de loco.

Le protagoniste du roman découvre que tout le monde autour de lui est "cannibale" et il est tellement effrayé qu'on le prend pour un fou.

小説の主人公は、自分の周りの人間が「人を食べている」ことを知り、あまりの怖さに狂人として退けられる。

O protagonista do romance descobre que toda a gente à sua volta está a "comer pessoas" e fica tão assustado que é considerado um louco.

实际上 ,“ 吃 人 ” 的 是 腐朽 的 封建主义 和 人们 的 愚昧 和 无知 , 而 那个 狂人 则 是 一个 善良 的 人 。

|||||||chủ nghĩa phong kiến|||||||||||||tốt bụng||

en réalité|||||pourri||féodalisme||||ignorance||ignorance|||fou|alors|||gentil||

In fact||cannibalism|possessive particle|is|decayed feudalism||feudalism|with|people||ignorance|and|ignorance|||madman|then|is||good||

In Wirklichkeit sind es der verrottete Feudalismus und die Unwissenheit und Dummheit der Menschen, die "Menschen fressen", während der Wahnsinnige ein guter Mensch ist.

In fact, the 'eating people' refers to the decaying feudalism and people's ignorance, while the madman is actually a kind person.

De hecho, fue el feudalismo decadente y la ignorancia y la incultura del pueblo lo que "se comió al hombre".

En fait, c'est le féodalisme pourri, l'ignorance et la stupidité des gens qui "mangent les gens", alors que le fou est un homme bon.

実際、「人を食った」のは退廃した封建制と民衆の無知蒙昧であったが、狂人は善人であった。

De facto, foi o feudalismo decadente e a ignorância e desconhecimento do povo que "comeram o homem", mas o louco era um homem bom.

《 狂人日记 》 使用 容易 理解 的 白话文 , 而 不是 文言文 , 也 就是 古代 的 书面语 。

|||||văn bạch thoại|||văn ngôn|||||văn viết cổ

Le Journal d'un fou (1)|||||langage courant|||langue classique|||||langue écrite

A Madman's Diary|uses|easy|understanding||vernacular Chinese|||Classical Chinese|||ancient||written language

Das Tagebuch eines Verrückten ist in leicht verständlicher Volkssprache geschrieben, nicht in der Literatursprache, der alten Schriftsprache.

'The Diary of a Madman' is written in easy-to-understand vernacular Chinese, rather than classical Chinese, which is the ancient written language.

El Diario de un loco está escrito en lengua vernácula de fácil comprensión, no en lengua literaria, que es la antigua lengua escrita.

Le Journal d'un fou est écrit en langue vernaculaire facilement compréhensible, et non en langue littéraire, qui est la langue écrite ancienne.

狂人日記』は、古代の書き言葉である文語ではなく、わかりやすい方言で書かれています。

O Diário de um Louco é escrito em vernáculo de fácil compreensão, não em linguagem literária, que é a linguagem escrita antiga.

紧接着 , 鲁迅 又 写 了 小说 《 孔乙己 》。

||||||Kong Yiji

juste après||||||Kong Yiji

Immediately after|Lu Xun|again|wrote|||Kong Yiji

Unmittelbar danach schrieb LU Xun den Roman Kong Yi Ji.

Immediately after, Lu Xun wrote the novel Kong Yiji.

Lu Xun escribió entonces su novela Kong Yiji.

Immédiatement après, LU Xun écrit le roman Kong Yi Ji.

魯迅はその後、小説『孔乙己』を執筆した。

Lu Xun escreveu então o seu romance Kong Yiji.

孔乙己 是 一个 只 知道 读书 的 人 , 他 的 目标 就是 通过 考试 当官 , 但 他 失败 了 。

||||||||||||passer||devenir fonctionnaire|||a échoué|

|||only|only knows|to read books|||||goal||to pass|exam|become an official|but||failed|

||||||||||||||стати官ом||||

Kong Yiji ist eine Person, die nur Bücher lesen kann. Sein Ziel ist es, die Prüfung zu bestehen und Beamter zu werden, aber er hat versagt.

Kong Yiji is a person who only knows how to read. His goal is to pass the exam, but he has failed.

Confucio era un hombre que sólo sabía estudiar y su objetivo era aprobar un examen para convertirse en funcionario, pero fracasó.

Kong Yijie est un homme qui ne sait que lire, et son objectif est de devenir fonctionnaire en passant l'examen, mais il échoue.

孔乙己は勉強しか知らない男で、試験に合格して官吏になることが目標だったが、失敗してしまった。

Confúcio era um homem que só sabia estudar e o seu objetivo era passar num exame para se tornar funcionário, mas falhou.

他 读的书 只能 用来 考试 , 却 无法 给 他 带来 食物 。

|livre||utiliser|examen||||||

|the books he reads||for the purpose of|exam|but|cannot|to give|him|bring|food

|книга, яку він читає|||||||||

Die Bücher, die er liest, können nur für Prüfungen verwendet werden, aber sie können ihm kein Essen bringen.

The book he read can only be used for examinations, but he cannot bring food to him.

Los libros que leía sólo le servían para los exámenes, pero no le daban de comer.

Les livres qu'il lit ne peuvent être utilisés que pour les examens, mais ils ne peuvent pas lui apporter de nourriture.

読んだ本は受験に使えるだけで、食べ物を運んでくることはできなかった。

Os livros que lia só podiam ser utilizados para os exames, mas não lhe davam comida.

他 没有 了 尊严 , 人们 嘲笑 他 。

|||||chế giễu|

|||dignité||se moquer de|

|||dignity||mocked|

|||гідність|||

Er verlor seine Würde und die Leute lachten über ihn.

He has no dignity, and people laugh at him.

Il n'a aucune dignité et les gens se moquent de lui.

威厳がなく、みんなに笑われた。

他 还 去 偷 书 , 结果 被 人 打 断了腿 。

|||||||||Gãy chân

||||livre|||||a cassé sa jambe

||to go|steal||as a result|||hit|broke his leg

|||||||||переломив ногу

Er wollte das Buch stehlen, war aber kaputt.

He went to steal books and ended up getting his legs broken by someone.

También fue a robar un libro y le rompieron una pierna.

Il est également allé voler des livres, a été battu et a eu les jambes cassées.

また、本を盗みに行って、足を折られたこともあったそうです。

Também foi roubar um livro e partiu uma perna.

鲁迅 通过 这个 可怜 的 人 讽刺 了 当时 的 社会 。

||||||châm biếm||||

|a travers||pauvre|||a ridiculisé||||société

Lu Xun|by||pitiful|||satirize||that time||society

|через||бідний|||сатира||||суспільство

Lu Xun verspottete die damalige Gesellschaft durch diesen armen Mann.

Lu Xun used this poor person to satirize the society at that time.

A través de este pobre hombre, Lu Xun satiriza la sociedad de su tiempo.

Lu Xun a fait la satire de la société de l'époque à travers ce pauvre homme.

魯迅はこの貧しい男を通して、当時の社会を風刺している。

Através deste pobre homem, Lu Xun satiriza a sociedade do seu tempo.

几年 后 , 鲁迅 又 发表 了 小说 《 阿Q正传 》。

quelques années|||||||"Le véritable récit d'Ah Q"

a few years||Lu Xun||published|||The True Story of Ah Q

||||опублікував||роман|"Справжня історія А'Q"

Einige Jahre später veröffentlichte Lu Xun den Roman Die wahre Geschichte von Ah Q.

Several years later, Lu Xun published the novel "The True Story of Ah Q".

Unos años más tarde, Lu Xun publicó otra novela, A Q Zhengzhuan.

数年後、鲁迅は小説『阿Q正伝』を発表しました。

Alguns anos mais tarde, Lu Xun publicou outro romance, A Q Zhengzhuan.

阿Q 很穷 , 也 不 知道 自己 的 名字 怎么 写 。

|très pauvre||||||||

Ah Q|very poor||||||name|how|

А Q|дуже бідний|||||||як|

Ah Q ist sehr arm und weiß nicht, wie er seinen Namen schreiben soll.

Ah Q is very poor and doesn't even know how to write his own name.

Q era muy pobre y no sabía escribir su nombre.

Ah Q était très pauvre et ne savait pas écrire son nom.

阿Qはとても貧しく、自分の名前をどう書くかもわかりません。

Q era muito pobre e não sabia escrever o seu nome.

他 很 可怜 , 却 不 努力 。

||đáng thương|||cố gắng

|||mais||

||pitiful|but||try

||бідний|але||працювати

Er ist sehr erbärmlich, aber er arbeitet nicht hart.

He is very pitiful, but not hardworking.

Es pobre, pero no lo intenta.

Il est pathétique, mais il n'essaie pas.

彼はとてもかわいそうですが、努力しません。

Ele é pobre, mas não se esforça.

为了 求生 , 他 发明 了 “ 精神 胜利 法 ”: 当 他 遭到 不幸 的 时候 , 就 在精神上 麻痹 自己 , 什么 都 不 去 想 。

|Sinh tồn|||||||||gặp phải||||||tê liệt||||||

|survie||a inventé||mental|victoire|méthode|||subit|malheur||||mentalement|paralysait||||||

|Survival||invented||spirit|victory|method|||suffered|misfortune||||mentally|numbness||anything|anything||to go|think

|виживання||||||метод||||нещастя||||в психологічному плані|паралізувати||||||

Um zu überleben, erfand er die "Spiritual Victory Method": Als er unglücklich war, lähmte er sich mental und dachte nichts.

In order to survive, he invented the "spiritual victory method": when he encountered misfortune, he would numb himself spiritually and not think about anything.

Para sobrevivir, inventó el "método del triunfo espiritual": cuando era golpeado por la desgracia, se paralizaba mentalmente y no pensaba en otra cosa.

Pour survivre, il invente la "méthode de la victoire spirituelle" : lorsqu'il est frappé par un malheur, il se paralyse mentalement et ne pense à rien d'autre.

生き延びるために、彼は不幸に見舞われたとき、精神的に麻痺して何も考えないという「精神勝利の方法」を編み出したのです。

Para sobreviver, inventou o "método do triunfo espiritual": quando era atingido pelo infortúnio, paralisava-se mentalmente e não pensava noutra coisa.

鲁迅 写 《 阿Q正传 》, 讽刺 了 中国 人 的 性格 问题 。

|||châm biếm||||||

Lu Xun||The True Story of Ah Q|satirizes|||||character traits|character

Лу Синь||"Алегорія А'Q"|сатира|||||характер|проблема

Lu Xun schrieb "Die wahre Geschichte von Ah Q", das das chinesische Schriftzeichen verspottete.

Lu Xun wrote 'The True Story of Ah Q', satirizing the character issues of the Chinese people.

Lu Xun a écrit "La véritable histoire d'Ah Q" pour faire la satire des problèmes de caractère des Chinois.

魯迅は、中国人の性格を風刺した「阿Qの実話」を書いた。

Lu Xun escreveu "A Verdadeira História de Ah Q", uma sátira sobre o carácter do povo chinês.

鲁迅 的 小说 收集 在 《 呐喊 》 和 《 彷徨 》 两本书 里面 。

|||recueillir||Nahan||Errance||

Lu Xun||novels|collection||Call to Arms||Wandering|two books|

|||збірка||Няня||Блукання|дві книги|

Lu Xuns Romane sind in zwei Büchern zusammengefasst, "Scream" und "Wandering".

Lu Xun's novels are collected in the two books 'Call to Arms' and 'Wandering'.

Las novelas de Lu Xun se recogen en dos libros, Na Yao y Wandering.

Les romans de Lu Xun sont rassemblés dans deux livres, Scream et Wandering.

魯迅の小説は『那么』と『彷徨』の2冊にまとめられています。

Os romances de Lu Xun estão reunidos em dois livros, Na Yao e Wandering.

后来 , 鲁迅 写 了 很多 散文 和 杂文 , 更加 直接 地 批评 当时 中国 的 各种 问题 。

|||||Tản văn||tạp văn|||||||||

||a écrit|||essais||essais critiques||directement|||||||

Later|Lu Xun||||prose||miscellaneous essays|even more|more directly|more directly|criticism|that time|||various|issues

|Лу Синь||||есе||фейлетони|більш|прямо||критика||||різні|проблеми

Später schrieb Lu Xun viele Essays und Essays und kritisierte verschiedene Probleme in China zu dieser Zeit direkter.

Later, Lu Xun wrote many prose and essays, more directly criticizing various issues in China at that time.

Más tarde, Lu Xun escribió muchos ensayos y artículos diversos para criticar más directamente los diversos problemas de la China de la época.

その後、魯迅は、当時の中国の諸問題をより直接的に批判するために、多くの随筆や雑文を書きました。

Mais tarde, Lu Xun escreveu muitos ensaios e artigos diversos para criticar mais diretamente os vários problemas da China da época.

他 的 著名 散文集 有 《 朝花夕拾 》 和 《 野草 》, 杂文集 有 《 二心 集 》 和 《 华盖 集 》。

|||Tập tản văn||||Cỏ dại|Tập tạp văn||||||

||fameux|recueil de prose||Les fleurs du matin et les souvenirs du soir||Herbes sauvages|recueil d'articles||Deux cœurs|ji (1)||Huagai|

|possessive particle|famous|Essay collection||Morning Flowers Evening Gatherings||Wild Grass|miscellaneous essays||Two Hearts|collection||Huagai Collection|collection

||відомий|збірка есе||"Ранкові квіти, вечірні збори"||Дикі трави|збірка нарисів||Двосердечність|||Хуаґай|

Zu seinen berühmten Aufsatzsammlungen gehören "Gesammelte Blumen am Abend" und "Wild Grass", und zu den Aufsatzsammlungen gehören "Essence Collection of Two Hearts" und "Collection of Huagai".

His famous prose collections include 'Dawn Blossoms Plucked at Dusk' and 'Wild Grass', while his essay collections include 'Two Hearts' and 'Huagai'.

Entre sus famosas colecciones de ensayos figuran Las flores de la mañana y Las hierbas silvestres, y entre sus ensayos misceláneos, La colección de los dos corazones y La colección Huagai.

有名なエッセイ集に『朝の花』『野の草』、雑文集に『二心集』『華厳集』などがある。

As suas famosas colecções de ensaios incluem The Flowers in the Morning e The Wild Grasses, e os seus ensaios diversos incluem The Two Hearts Collection e The Huagai Collection.

鲁迅 对 中国 古代文学 做 了 一些 研究 。

|||||||recherches

Lu Xun|||ancient literature||||research

|||давня література||||дослідження

Lu Xun forschte über alte chinesische Literatur.

Lu Xun also did some research on ancient Chinese literature.

Lu Xun ha investigado sobre la literatura china antigua.

魯迅は古代中国の文献を研究したことがある。

Lu Xun fez algumas pesquisas sobre a literatura chinesa antiga.

除此之外 , 鲁迅 也 翻译 了 很多 外国 的 文学作品 , 把 各种 新 思想 介绍 到 中国 。

|||dịch thuật||||||||||||

en plus de cela||||||||œuvres littéraires|||||||

In addition|Lu Xun||translated|||||literary works|introduced|various|new|thoughts|introduced|to|

окрім цього||||||||літературні твори|||||||

Darüber hinaus übersetzte Lu Xun auch viele ausländische literarische Werke und brachte verschiedene neue Ideen nach China.

In addition, Lu Xun also translated many foreign literary works and introduced various new ideas to China.

Además, Lu Xun también tradujo muchas obras literarias extranjeras e introdujo nuevas ideas en China.

また、魯迅は海外の文学作品を数多く翻訳し、中国に新しい思想を紹介しました。

Além disso, Lu Xun também traduziu muitas obras literárias estrangeiras e introduziu novas ideias na China.

鲁迅 相信 民主 , 支持 学生 运动 , 也 因此 得罪 了 当时 的 政府 。

|||||phong trào|||||||

||démocratie|soutenir|||||a offensé||||

Lu Xun|believed|democracy|supported|students|movement||therefore|offend||the time||government

||||||||образив||||

Lu Xun glaubte an Demokratie und unterstützte die Studentenbewegung, die die damalige Regierung beleidigte.

Lu Xun believed in democracy, supported the student movement, and therefore offended the government at the time.

Lu Xun creía en la democracia y apoyó el movimiento estudiantil, ofendiendo así al gobierno de la época.

LU Xun croyait en la démocratie et soutenait le mouvement étudiant, ce qui a heurté le gouvernement de l'époque.

魯迅は民主主義を信じ、学生運動を支持したため、当時の政府を怒らせた。

Lu Xun acreditava na democracia e apoiou o movimento estudantil, ofendendo assim o governo da época.

他 曾经 在 北京 的 政府 工作 , 后来 逃 到 南方 。

|aussi|||||||s'est échappé||

|once||||the government|worked|later|escaped||the south

Er arbeitete in der Regierung von Peking und floh später in den Süden.

He used to work in the government of Beijing and later fled to the south.

北京の政府機関で働いた後、南部に逃亡した。

Trabalhou para o governo em Pequim antes de fugir para o sul.

他 在 各地 的 大学 给 学生 上课 、 演讲 , 影响 了 很多 人 , 特别 是 年轻人 。

||||||||diễn thuyết|||||||

||||||||a donné une conférence|||||||

||various places||universities|to give|students|teaching|speech|influenced||||especially||young people

Er hielt Vorlesungen und Vorlesungen für Studenten an Universitäten überall und betraf viele Menschen, insbesondere junge Menschen.

He taught and gave lectures to students at universities around the world, affecting many people, especially young people.

Il a donné des conférences et des discours aux étudiants des universités du monde entier et a influencé de nombreuses personnes, en particulier des jeunes.

世界中の大学で講義や講演を行い、多くの人々、特に若者に影響を与えた。

Deu palestras e falou a estudantes em universidades de todo o mundo, influenciando muitas pessoas, especialmente os jovens.

直到 今天 , 人们 依然 认为 鲁迅 是 中国 最 重要 的 作家 、 思想家 和 革命家 。

jusqu'à|||toujours|||||||||philosophe||révolutionnaire

until|today|people|still|believe|Lu Xun||||||writer|thinker||revolutionary

||||||||||||філософ||революціонер

Bis heute gilt Lu Xun als Chinas wichtigster Schriftsteller, Denker und Revolutionär.

To this day, people still believe that Lu Xun is China's most important writer, thinker and revolutionary.

Aujourd'hui encore, LU Xun est considéré comme l'écrivain, le penseur et le révolutionnaire le plus important de Chine.

今日に至るまで、魯迅は中国の最も重要な作家、思想家、革命家として評価されている。

听说 最近 教科书 里 鲁迅 的 文章 被 删除 了 , 这 引起 了 人们 的 讨论 。

||||||||xóa bỏ|||gây ra||||

||manuel scolaire||||||supprimé|||a suscité||||

I heard that|recently|textbook||Lu Xun||article|by|deleted|past tense marker||caused||||discussion

||||||||видалено|||||||

Ich habe gehört, dass der Artikel von Lu Xun im Lehrbuch kürzlich gelöscht wurde, was die Diskussion der Leute anregte.

I heard that recently, articles by Lu Xun in textbooks have been deleted, which has caused a lot of discussion.

He oído que los artículos de Lu Xun han sido retirados recientemente de los libros de texto, lo que ha suscitado un gran debate.

J'ai entendu dire que les articles de Lu Xun ont récemment été supprimés des manuels scolaires, ce qui a suscité de nombreuses discussions.

最近、魯迅の論文が教科書から削除され、話題になっていると聞いています。

Ouvi dizer que os artigos de Lu Xun foram recentemente retirados dos manuais escolares, o que suscitou muita discussão.

支持者 说 , 因为 鲁迅 已经 不能 代表 这个 时代 了 ; 反对者 说 , 因为 鲁迅 笔下 的 人 全部 复活 了 。

||||||||||||||||||sống lại|

partisan||||||représenter||||l'opposant||||||||revivent|

supporters|||Lu Xun|already|can no longer|speak for||era||opponents||because|Lu Xun|under his pen|||all|resurrect|

підтримувач||||||||||опонент||||||||воскресли|

Unterstützer sagen, weil Lu Xun diese Ära nicht mehr repräsentieren kann, sagen Gegner, weil alle von Lu Xun beschriebenen Menschen auferstanden sind.

Supporters say that Lu Xun can no longer represent this era; opponents say that all the people depicted by Lu Xun have come back to life.

Los partidarios dicen que Lu Xun ya no representa su época; los detractores, que todas las personas sobre las que escribió han vuelto a la vida.

Les partisans disent que c'est parce que LU Xun ne peut plus représenter cette époque ; les opposants disent que c'est parce que tous les personnages des écrits de LU Xun sont revenus à la vie.

賛成派は「魯迅はもはや時代を代表しない」と言い、反対派は「魯迅が書いた人物はすべて生き返った」と言う。

Os defensores dizem que Lu Xun já não representa o seu tempo; os opositores dizem que todas as pessoas sobre as quais escreveu voltaram à vida.