CHAPTER I. THE BOBBSEY TWINS AT HOME

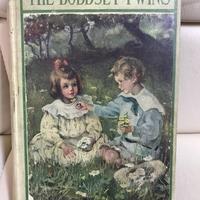

The Bobbsey twins were very busy that morning. They were all seated around the dining-room table, making houses and furnishing them. The houses were being made out of pasteboard shoe boxes, and had square holes cut in them for doors, and other long holes for windows, and had pasteboard chairs and tables, and bits of dress goods for carpets and rugs, and bits of tissue paper stuck up to the windows for lace curtains. Three of the houses were long and low, but Bert had placed his box on one end and divided it into five stories, and Flossie said it looked exactly like a "department" house in New York. There were four of the twins. Now that sounds funny, doesn't it? But, you see, there were two sets. Bert and Nan, age eight, and Freddie and Flossie, age four.

Nan was a tall and slender girl, with a dark face and red cheeks. Her eyes were a deep brown and so were the curls that clustered around her head.

Bert was indeed a twin, not only because he was the same age as Nan, but because he looked so very much like her. To be sure, he looked like a boy, while she looked like a girl, but he had the same dark complexion, the same brown eyes and hair, and his voice was very much the same, only stronger.

Freddie and Flossie were just the opposite of their larger brother and sister. Each was short and stout, with a fair, round face, light-blue eyes and fluffy golden hair. Sometimes Papa Bobbsey called Flossie his little Fat Fairy, which always made her laugh. But Freddie didn't want to be called a fairy, so his papa called him the Fat Fireman, which pleased him very much, and made him rush around the house shouting: "Fire! fire! Clear the track for Number Two! Play away, boys, play away!" in a manner that seemed very lifelike. During the past year Freddie had seen two fires, and the work of the firemen had interested him deeply.

The Bobbsey family lived in the large town of Lakeport, situated at the head of Lake Metoka, a clear and beautiful sheet of water upon which the twins loved to go boating. Mr. Richard Bobbsey was a lumber merchant, with a large yard and docks on the lake shore, and a saw and planing mill close by. The house was a quarter of a mile away, on a fashionable street and had a small but nice garden around it, and a barn in the rear, in which the children loved at times to play.

"I'm going to cut out a fancy table cover for my parlor table," said Nan. "It's going to be the finest table cover that ever was." "Nice as Aunt Emily's?" questioned Bert. "She's got a—a dandy, all worked in roses." "This is going to be white, like the lace window curtains," replied Nan. While Freddie and Flossie watched her with deep interest, she took a small square of tissue paper and folded it up several times. Then she cut curious-looking holes in the folded piece with a sharp pair of scissors. When the paper was unfolded once more a truly beautiful pattern appeared.

"Oh, how lubby!" screamed Flossie. "Make me one, Nan!" "And me, too," put in Freddie. "I want a real red one," and he brought forth a bit of red pin-wheel paper he had been saving. "Oh, Freddie, let me have the red paper for my stairs," cried Bert, who had had his eyes on the sheet for some time. "No, I want a table cover, like Nanny. You take the white paper." "Whoever saw white paper on a stairs—I mean white carpet," said Flossie. "I'll give you a marble for the paper, Freddie," continued Bert. But Freddie shook his head. "Want a table cover, nice as Aunt Em'ly," he answered. "Going to set a flower on the table too!" he added, and ran out of the room. When he came back he had a flower-pot in his hand half the size of his house, with a duster feather stuck in the dirt, for a flower.

"Well, I declare!" cried Nan, and burst out laughing. "Oh, Freddie, how will we ever set that on such a little pasteboard table?" "Can set it there!" declared the little fellow, and before Nan could stop him the flower-pot went up and the pasteboard table came down and was mashed flat.

"Hullo! Freddie's breaking up housekeeping!" cried Bert.

"Oh, Freddie! do take the flower-pot away!" came from Flossie. "It's too big to go into the house." Freddie looked perplexed for a moment. "Going to play garden around the house. This is a—a lilac tree!" And he set the flower-pot down close to Bert's elbow. Bert was now busy trying to put a pasteboard chimney on his house, and did not notice. A moment later Bert's elbow hit the flower-pot and down it went on the floor, breaking into several pieces and scattering the dirt over the rug. "Oh, Bert! what have you done?" cried Nan, in alarm. "Get the broom and the dust-pan, before Dinah comes." "It was Freddie's fault." "Oh, my lilac tree is all gone!" cried the little boy. "And the boiler to my fire engine, too," he added, referring to the flower-pot, which he had used the day before when playing fireman. At that moment, Dinah, the cook, came in from the kitchen.

"Well, I declar' to gracious!" she exclaimed. "If yo' chillun ain't gone an' mussed up de floah ag'in!" "Bert broke my boiler!" said Freddie, and began to cry.

"Oh, never mind, Freddie, there are plenty of others in the cellar," declared Nan. "It was an accident, Dinah," she added, to the cook. "Eberyt'ing in dis house wot happens is an accident," grumbled the cook, and went off to get the dust-pan and broom. As soon as the muss had been cleared away Nan cut out the red table cover for Freddie, which made him forget the loss of the "lilac tree" and the "boiler." "Let us make a row of houses," suggested Flossie. "Bert's big house can be at the head of the street." And this suggestion was carried out. Fortunately, more pasteboard boxes were to be had, and from these they made shade trees and some benches, and Bert cut out a pasteboard horse and cart. To be sure, the horse did not look very lifelike, but they all played it was a horse and that was enough. When the work was complete they called Dinah in to admire it, which she did standing near the doorway with her fat hands resting on her hips.

"I do declar', it looks most tremend'us real," said the cook. "It's a wonder to me yo' chillun can make sech t'ings." "We learned it in the kindergarten class at school," answered Nan. "Yes, in the kindergarten," put in Flossie. "But we don't make fire engines there," came from Freddie. At this Dinah began to laugh, shaking from head to foot.

"Fire enjuns, am it, Freddie? Reckon yo' is gwine to be a fireman when yo' is a man, hey?" "Yes, I'm going to be a real fireman," was the ready answer. "An' what am yo' gwine to be, Master Bert?" "Oh, I'm going to be a soldier," said Bert. "I want to be a soldier, too," put in Freddie. "A soldier and a fireman." "Oh, dear, I shouldn't want to be a soldier and kill folks," said Nan. "Girls can't be soldiers," answered Freddie. "They have to get married, or be dressmakers, or sten'graphers, or something like that." "You mean sten o graphers, Bert. I'm going to be a sten o grapher when I get big." "I don't want to be any sten o gerer," put in Flossie. "I'm going to keep a candy store, and have all the candy I want, and ice cream" "Me too!" burst in Freddie. "I'm going to have a candy store, an' be a fireman, an' a soldier, all together!" "Dear! dear!" laughed Dinah. "Jess to heah dat now! It's wonderful wot yo' is gwine to be when yo' is big." At that moment the front door bell rang, and all rushed to the hallway, to greet their mother, who had been down-town, on a shopping tour.