28. Victory for the Greeks

"A king sat on the rocky brow Which looks o'er sea-born Salamis: And ships, by thousands, lay below, And men in nations:—all were his. He counted them at break of day— And when the sun set, where were they?" —BYRON.

Having gained the pass, it was natural that Xerxes should lead his army on to Athens. The Spartans did not care, whether Athens fell into the hands of the Persians, or not. They wished to save Corinth, and so save South Greece, where lay their own land; for Greece was not a united country; each little state wanted what it could get for itself.

The men of Athens knew it was hopeless to try and defend their city alone, against the whole Persian army, so they resolved to abandon it. Very full of sorrow, men, women, and children left their homes and streamed down to the sea-shore, carrying what they could with them. There they found the Greek ships waiting to bear them away, and so when Xerxes and his mighty army reached Athens, they found it silent and deserted. Only a few poor and desperate men had refused to depart, and had posted themselves on the top of the Acropolis, the fortress of Athens. The Persians, disappointed of their prey, took their revenge. They stormed the Acropolis, slew the brave defenders, and set the town on fire.

Athens had fallen. There was but one hope now for the Greeks. They had their ships. Themistocles had been right after all. The ships were yet to save the country.

When Xerxes had advanced to Athens, his fleet had sailed along the coast, and was now anchored. The Greek fleet lay but a few miles off, close to the large island of Salamis, between Athens on the one side and Corinth on the other.

A council of Greeks was held. Themistocles rose to speak at once and to urge a naval battle without delay. The Corinthian general was very angry.

"O Themistocles," he cried, "those who stand up too soon in the games, are whipped." "Yes," answered Themistocles, "but those who start late, are not crowned." He saw that the Greeks must fight at once, or in their despair at the loss of Athens, they might not remain faithful. Still he could not get others to see things from his point of view, so he thought of a plan to bring on the battle quickly. He sent a trusty slave across the narrow strait to the Persian admiral, saying that the Greeks were panic-stricken and about to escape. The Persian admiral fell into the trap. In the dead of night, he moved his fleet noiselessly round and blocked up the narrow inlet of the strait, so that the Greeks could not escape.

Early next morning—it was still dark, and the commanders were sitting at council, when Themistocles was called out by a stranger. It was the exile Aristides. In the ruin and distress of Athens, he had come to serve those, who had banished him, and had made his way through the Persian fleet in the darkness, to tell the Greek commanders, that they had been surrounded.

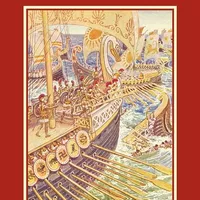

"Themistocles," he urged, "let us still be rivals, but let our contest be, who best shall serve our country." As the rising sun of the September morning cast its shadows across the blue Bay of Salamis, the Greek fleet put out from shore, to the accustomed notes of the war hymn to Apollo. The enemy's ships faced them all across the narrow strait, stretching far away to right and left, and cutting off all chance of escape. Behind the Persian ships the Persian army was drawn up along the shore, and a lofty throne was set in the midst, from which the great King Xerxes could survey the battle. The Persian fleet advanced, and the Greeks, seized with terror, began to back their oars towards the shore.

Soon the two fleets were engaged. The Greeks fought in good order and kept their ships in line, while the Persian fleet was soon in confusion, oars and helms were broken, ships lay helpless on the water. The old vessels had no rudders, but were steered with broad blades. Confusion soon became a panic. Vessel crashed against vessel. Persian ships were jammed together in the narrow space. Beaten and disabled, they disappeared under the very eyes of Xerxes the king. Some two hundred were thus destroyed, and the rest fled out of the narrow strait. By sunset the battle was over. The Greeks had won their victory and saved their country from the Persians.

And so the great conflict between Eastern tyranny and European freedom was over. Marathon, Thermopylæ, Salamis close one of the most important and thrilling chapters in the world's great history.