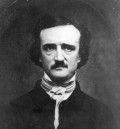

A Cask of Amontillado by Edgar Allan Poe

یک|بشکه|از|آمانتیلادو|توسط|ادگار|آلن|پو

một|thùng|của|Amontillado|của|Edgar|Allan|Poe

A|бочка|з|Амонтильядо|від|Едгар|Аллан|По

||of|a type of sherry||Edgar Allan Poe|Edgar Allan Poe|Edgar Allan Poe

علبة|برميل|من|أمونتيادو|بواسطة|إدغار|ألان|بو

a|beczka|z|Amontillado|autorstwa|Edgara|Allana|Poe'a

|酒桶||雪莉酒||埃德加||

bir|fıçı|-nin|Amontillado|-den|Edgar|Allan|Poe

Ein|Fass|von|Amontillado|von|Edgar|Allan|Poe

|fût||Amontillado||||

un|barril|de|Amontillado|por|Edgar|Allan|Poe

Le Masque d'Amontillado d'Edgar Allan Poe

Il castello di Amontillado di Edgar Allan Poe

エドガー・アラン・ポーによるアモンティリヤアドの樽

에드거 앨런 포의 아몬티야도 상자

O Barril de Amontillado de Edgar Allan Poe

Бочонок Амонтильядо" Эдгара Аллана По

A Cask of Amontillado av Edgar Allan Poe

埃德加爱伦坡的一桶阿蒙蒂拉多

愛倫坡 (Edgar Allan Poe) 的一桶阿蒙蒂亞多 (Amontillado)

Un barril de Amontillado de Edgar Allan Poe

Ein Fass Amontillado von Edgar Allan Poe

Бочка Амонтильядо Едгара Аллана По

یک بشکه آمانتیلا دو از ادگار آلن پو

برميل من أمونتيلادو بقلم إدغار آلان بو

Một thùng Amontillado của Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe'nun Amontillado Fıçısi

Beczka Amontillado autorstwa Edgara Allana Poe

The thousand injuries of Fortunato I had borne as I best could; but when he ventured upon insult, I vowed revenge.

(مقاله تعریف کننده)|هزار|جراحات|از|فورتوناتو|من|داشت|تحمل کرده بود|به اندازه ای که|من|بهترین|می توانست|اما|وقتی که|او|جرات کرد|بر|توهین|من|قسم خوردم|انتقام

những|ngàn|thương tích|của|Fortunato|tôi|đã|chịu đựng|như|tôi|tốt nhất|có thể|nhưng|khi|anh ta|dám|vào|xúc phạm|tôi|thề|trả thù

Тисячу||образ|Фортунато|Фортунато|Я|мав|витримав|як|Я|найкраще|міг|але|коли|він|наважився|на|образу|Я|поклявся|помсту

The|one thousand|harm offenses||Fortunato|I|had endured|endured||I|most|was able to|however|at the moment|Fortunato|took a risk|to the point of|offense|I|swore revenge|retribution

الجملة|ألف|إصابات|من|فورتونات|أنا|كان|تحملت|كما|أنا|أفضل|استطعت|لكن|عندما|هو|تجرأ|على|إهانة|أنا|أقسمت|انتقام

tysiąc|tysiąc|obrażeń|od|Fortunata|ja|miałem|znosiłem|jak|ja|najlepiej|mogłem|ale|kiedy|on|odważył się|na|zniewagę|ja|przysiągłem|zemstę

|千次伤害|伤害||福图纳托|||忍受||||||||冒犯|对|侮辱||发誓|复仇

o|bin|yaralar|-nin|Fortunato|ben|-di|katlandım|-dığı gibi|ben|en iyi|-ebildim|ama|-dığında|o|cesaret etti|üzerine|hakaret|ben|yemin ettim|intikam

Die|tausend|Verletzungen|von|Fortunato|ich|hatte|ertragen|so gut|ich|bestmöglich|konnte|aber|als|er|wagte|auf|Beleidigung|ich|schwor|Rache

las|mil|heridas|de|fortunato|yo|había|soportado|como|yo|mejor|pude|pero|cuando|él|se atrevió|a|insulto|yo|juré|venganza

Fortunatos tusind skader havde jeg båret over med, så godt jeg kunne, men da han vovede at fornærme mig, svor jeg hævn.

The thousand injuries of Fortunato I had borne as I best could; but when he ventured upon insult, I vowed revenge.

私が最善を尽くして負ったフォルトゥナートの千の怪我。しかし、彼が侮辱に挑戦したとき、私は復讐を誓った。

Тысячи ран Фортунато я перенес, как мог; но когда он осмелился на оскорбление, я поклялся отомстить.

การบาดเจ็บพันอย่างของฟอร์ตูนาโต ฉันได้อดทนมาอย่างดีที่สุด; แต่เมื่อเขาได้กล่าวเหยียดหยาม ฉันสาบานว่าจะล้างแค้น.

福爾圖納託的千百次傷害我已盡我所能承受;但當他敢於侮辱我時,我發誓要報仇。

Las mil injurias de Fortunato las había soportado lo mejor que pude; pero cuando se atrevió a insultar, juré venganza.

Die tausend Verletzungen, die ich von Fortunato erlitten hatte, hatte ich so gut ich konnte ertragen; aber als er es wagte, mich zu beleidigen, schwor ich Rache.

Тисячу образ Фортуна я терпів, як міг; але коли він наважився на образу, я поклявся помститися.

هزار آسیب فورتوناتو را تا جایی که میتوانستم تحمل کرده بودم؛ اما وقتی او به توهین پرداخت، انتقام را قسم خوردم.

تحملت ألف جرح من فورتوناتيو كما استطعت؛ ولكن عندما تجرأ على الإهانة، أقسمت على الانتقام.

Tôi đã chịu đựng hàng ngàn sự xúc phạm của Fortunato như tôi có thể; nhưng khi anh ta dám xúc phạm, tôi đã thề sẽ trả thù.

Fortunato'nun binlerce yarasına dayanabildiğim kadar dayandım; ama o hakarete cüret ettiğinde, intikam almaya yemin ettim.

Tysiąc krzywd, które wyrządził mi Fortunato, znosiłem najlepiej jak potrafiłem; ale gdy tylko odważył się na zniewagę, przysiągłem zemstę.

You, who so well know the nature of my soul, will not suppose, however, that I gave utterance to a threat.

تو|که|به این اندازه|خوب|میدانی|(حرف تعریف)|طبیعت|(حرف اضافه)|من|روح|(فعل کمکی آینده)|نه|فرض کن|با این حال|که|من|دادم|بیان|به|(حرف تعریف نکره)|تهدید

bạn|người|rất|tốt|biết|bản chất|bản chất|của|tôi|linh hồn|sẽ|không|nghĩ|tuy nhiên|rằng|tôi|đã đưa|phát biểu|đến|một|lời đe dọa

Ти|хто|так|добре|знаєш|природу|природу|моєї|моєї|душі|будеш|не|припустиш|однак|що|я|дав|висловлення|до|одного|погрози

You||very||understand||||my|spirit|future tense verb|will not|assume|but rather|that I||expressed|expression|to||intimidation

أنت|الذي|جدا|جيدا|تعرف|طبيعة|طبيعة|من|روحي|روح|سوف|لا|تظن|ومع ذلك|أن|أنا|أعطيت|تعبير|إلى|تهديد|تهديد

ty|który|tak|dobrze|znasz|naturę|naturę|mojej|mojej|duszy|będziesz|nie|przypuszczać|jednak|że|ja|dałem|wyraz|do|groźby|groźbie

||||||本性|||灵魂|||假设|||||说出话来|||威胁

sen|kim|o kadar|iyi|biliyorsun|-in|doğası|-nin|benim|ruh|-ecek|değil|varsayacaksın|ancak|ki|ben|verdim|ifade|-e|bir|tehdit

Du|der|so|gut|kennst|die|Natur|meiner||Seele|wirst|nicht|annehmen|jedoch|dass|ich|gab|Äußerung|zu|einer|Drohung

tú|quien|tan|bien|conoces|la|naturaleza|de|mi|alma|(verbo auxiliar futuro)|no|supongas|sin embargo|que|yo|di|expresión|a|una|amenaza

Du, som kender min sjæls natur så godt, vil dog ikke tro, at jeg fremsatte en trussel.

しかし、私の魂の性質をよく知っているあなたは、私が脅威に発話したとは思わないでしょう。

คุณ ที่รู้จักธรรมชาติของจิตวิญญาณของฉันเป็นอย่างดี จะไม่คิดว่าฉันได้กล่าวคำข่มขู่.

然而,你如此了解我靈魂的本質,不會認為我說出了威脅的話。

Tú, que conoces tan bien la naturaleza de mi alma, no suponerás, sin embargo, que expresé una amenaza.

Ihr, die ihr die Natur meiner Seele so gut kennt, werdet jedoch nicht annehmen, dass ich eine Drohung ausgesprochen habe.

Ти, хто так добре знає природу моєї душі, не будеш, однак, вважати, що я висловив загрозу.

شما که به خوبی طبیعت روح من را میشناسید، هرگز تصور نخواهید کرد که من تهدیدی را بیان کردهام.

أنت، الذي تعرف جيدًا طبيعة روحي، لن تظن، مع ذلك، أنني أصدرت تهديدًا.

Bạn, người hiểu rõ bản chất của tâm hồn tôi, sẽ không nghĩ rằng tôi đã phát ra một lời đe dọa.

Sen, ruhumun doğasını çok iyi bilen, bir tehditte bulunduğumu sanmayacaksın.

Ty, który tak dobrze znasz naturę mojej duszy, nie pomyślisz jednak, że wyraziłem groźbę.

At length I would be avenged; this was a point definitively settled - but the very definitiveness with which it was resolved, precluded the idea of risk.

در|نهایت|من|می|بود|انتقام گرفته شده|این|بود|یک|نقطه|به طور قطعی|حل شده|اما|آن|بسیار|قطعی بودن|با|که|آن|بود|حل شده|مانع شد|آن|ایده|از|ریسک

vào|cuối cùng|tôi|sẽ|bị|trả thù|điều này|đã|một|điểm|dứt khoát|đã được quyết định|nhưng|sự|rất|tính dứt khoát|với|mà|nó|đã|được quyết định|ngăn cản|ý tưởng|ý tưởng|về|rủi ro

Нарешті|довго|я|б|бути|помщеним|це|було|один|момент|остаточно|вирішений|але|той|сам|остаточність|з|якою|це|було|вирішено|виключало|ідею|ідею|ризику|ризику

In the end|at last|I|would|become|taken revenge|this matter|was||matter|certainly established|settled|but|the|emphatic|certainty|with|with which|it|was|settled definitively|ruled out|the|idea|of|risk

في|النهاية|أنا|سوف|أكون|منتقما|هذا|كان|نقطة|نقطة|بشكل نهائي|تم حسمها|لكن|ال|نفس|الحسم|مع|الذي|تم|كان|حسم|استبعد|الفكرة|فكرة|من|خطر

na|w końcu|ja|bym|był|pomszczony|to|było|punkt|punkt|definitywnie|ustalony|ale|sama|sama|definitywność|z|którą|to|było|postanowione|wykluczyło|myśl|myśl|o|ryzyku

|||||复仇成功|||||明确地|确定||||确定性|以...方式||||解决了|排除了||风险的念头||风险

sonunda|uzunluk|ben|-ecektim|-ecek|intikam alındı|bu|-di|bir|nokta|kesin olarak|kararlaştırıldı|ama|o|çok|kesinlik|ile|ki|bu|-di|kararlaştırıldı|engelledi|o|fikir|-in|risk

Schließlich|Länge|ich|würde|sein|gerächt|dies|war|ein|Punkt|endgültig|entschieden|aber|die|sehr|Definitheit|mit|der|es|war|gelöst|schloss aus|die|Idee|von|Risiko

a|largo|yo|(verbo auxiliar)|estaré|vengado|esto|fue|un|punto|definitivamente|resuelto|pero|la|misma|definitividad|con|la cual|eso|fue|resuelto|excluyó|la|idea|de|riesgo

とうとう私は復讐されるでしょう。これは決定的に解決されたポイントでした-しかし、それが解決された非常に決定的なものは、リスクの考えを排除しました。

ในที่สุดฉันจะได้รับการล้างแค้น; นี่เป็นจุดที่ตกลงกันอย่างชัดเจน - แต่ความชัดเจนที่มันถูกกำหนดไว้นั้น ทำให้แนวคิดเรื่องความเสี่ยงไม่เกิดขึ้น.

終於我會報仇了;這是一個已經明確解決的問題——但解決問題的明確性排除了風險的想法。

Por fin sería vengado; este era un punto definitivamente resuelto - pero la misma definitividad con la que se resolvió, excluyó la idea de riesgo.

Endlich würde ich mich rächen; das war ein Punkt, der endgültig festgelegt war - aber die sehr Definitheit, mit der es beschlossen wurde, schloss die Idee des Risikos aus.

Нарешті я мав бути помщений; це було остаточно вирішено - але сама остаточність, з якою це було вирішено, виключала ідею ризику.

بالاخره من انتقام میگرفتم؛ این یک نکته به طور قطعی حل شده بود - اما همان قطعی بودن که با آن حل شده بود، ایده ریسک را منتفی میکرد.

في النهاية سأنتقم؛ كانت هذه نقطة تم حسمها بشكل نهائي - لكن الحسم التام الذي تم به، استبعد فكرة المخاطرة.

Cuối cùng tôi sẽ được báo thù; đây là một điểm đã được xác định rõ ràng - nhưng chính sự xác định rõ ràng mà nó được giải quyết đã ngăn cản ý tưởng về rủi ro.

Sonunda intikamımı alacaktım; bu kesin olarak kararlaştırılmış bir noktaydı - ama bunun kesinliği, risk fikrini ortadan kaldırıyordu.

W końcu miałem się zemścić; to było definitywnie ustalone - ale sama definitywność, z jaką to postanowiono, wykluczała myśl o ryzyku.

I must not only punish, but punish with impunity.

من|باید|نه|تنها|تنبیه کنم|بلکه|تنبیه کنم|با|بیمجازات

tôi|phải|không|chỉ|trừng phạt|nhưng|trừng phạt|với|sự miễn trách

Я|повинен|не|тільки|карати|але|карати|з|безкарністю

||||||||impunity

أنا|يجب|لا|فقط|أعاقب|لكن|أعاقب|مع|إفلات

ja|muszę|nie|tylko|karać|ale|karać|z|bezkarnością

||||惩罚||||逍遥法外

ben|-malıyım|değil|sadece|cezalandırmak|ama|cezalandırmak|ile|cezasızlık

Ich|muss|nicht|nur|bestrafen|sondern|bestrafen|mit|Straflosigkeit

yo|debo|no|solo|castigar|sino|castigar|con|impunidad

私は罰するだけでなく、罰せずに罰しなければなりません。

我不僅要懲罰,而且要懲罰而不受懲罰。

No solo debo castigar, sino castigar con impunidad.

Ich muss nicht nur bestrafen, sondern mit Straflosigkeit bestrafen.

Я повинен не лише карати, але й карати безкарно.

من نه تنها باید مجازات کنم، بلکه باید با مصونیت مجازات کنم.

يجب أن أعاقب، ولكن أعاقب بلا عقاب.

Tôi không chỉ phải trừng phạt, mà còn phải trừng phạt mà không bị trừng phạt.

Sadece ceza vermekle kalmamalıyım, aynı zamanda cezamı cezasız vermeliyim.

Nie mogę tylko karać, ale karać bezkarnie.

A wrong is unredressed when retribution overtakes its redresser.

یک|خطا|است|بدون جبران|وقتی|انتقام|برمیدارد|جبرانکننده|جبرانکننده

một|sai lầm|thì|không được đền bù|khi|sự trả thù|vượt qua|của nó|người đền bù

A|кривда|є|нерозплачена|коли|помста|випереджає|її|виправник

|||unredressed||retribution|||redresser

خطأ|خطأ|يكون|غير مُعاقب|عندما|انتقام|يتجاوز|مُعاقب|مُعاقب

krzywda|krzywda|jest|nieodwzajemniona|kiedy|zemsta|dogania|jej|odwetowca

|错误||未补偿的||报应|超越||纠正者

bir|yanlış|-dir|telafi edilmemiş|-dığında|intikam|yetiştiğinde|onun|telafi edeni

Ein|Unrecht|ist|ungesühnt|wenn|Vergeltung|überholt|seinen|Rächer

una|falta|está|sin reparar|cuando|la retribución|alcanza|su|reparador

報復がその救済者を追い抜くとき、間違ったものは救済されません。

當報應超過糾正者時,錯誤就無法糾正。

Una injusticia no se corrige cuando la retribución alcanza a quien la corrige.

Ein Unrecht bleibt ungesühnt, wenn die Vergeltung den Vergelter überholt.

Зло залишається невиправленим, коли помста наздоганяє свого відплатника.

یک ظلم زمانی جبران نشده است که انتقامجو بر انتقامگیرنده غلبه کند.

الظلم لا يُعالج عندما تتجاوز العقوبة المعاقب.

Một điều sai trái không được sửa chữa khi sự báo thù vượt qua người sửa chữa nó.

Bir yanlış, intikam alanın intikamını aldığı zaman düzeltilmemiştir.

Zło nie jest naprawione, gdy zemsta dopada swojego sprawcę.

It is equally unredressed when the avenger fails to make himself felt as such to him who has done the wrong.

آن|است|به یک اندازه|بیپاسخ مانده|وقتی که|(حرف تعریف)|انتقامگیرنده|ناکام میماند|به|ایجاد کردن|خود|احساس شده|به عنوان|چنین|به|او|کسی که|دارد|انجام داده|(حرف تعریف)|نادرستی

điều đó|thì|cũng|không được đền bù|khi|người|kẻ trả thù|thất bại|để|làm|bản thân mình|cảm nhận|như|vậy|với|người|người|đã|làm|cái|sai lầm

Це|є|однаково|не відшкодоване|коли||мстивець|не вдається||зробити|себе|відчутимим|як|таким||йому|хто|вчинив|зроблене||зло

ذلك|يكون|بالتساوي|غير مُعاقب|عندما|المنتقم|المنتقم|يفشل|في|جعل|نفسه|محسوس|ك|مثل|إلى|له|الذي|قد|فعل|الخطأ|الخطأ

to|jest|równie|nieodwzajemniona|kiedy|ten|mściciel|nie udaje się|aby|sprawić|siebie|odczuwanym|jako|taki|dla|niego|który|ma|zrobioną|tę|krzywdę

||同样地|未补偿的|||复仇者|未能成功||||感受到||那样的|||||||

bu|-dir|eşit derecede|telafi edilmemiş|-dığında|intikamcı|intikamcı|başarısız olduğunda|-mek|yapmak|kendisini|hissettirmek|olarak|böyle|-e|ona|kim|-dir|yapmış|yanlış|yanlış

Es|ist|ebenso|ungesühnt|wenn|der|Rächer|versagt|zu|machen|sich|fühlbar|als|solcher|zu|ihm|der|hat|getan|das|Unrecht

ello|es|igualmente|no reparado|cuando|el|vengador|falla|a|hacer|sí mismo|sentir|como|tal|a|él|quien|ha|hecho|el|mal

復讐者が間違ったことをした彼にそのように感じさせることができないとき、それは同様に救済されません。

当复仇者未能让犯了错的人感受到他的存在,同样也未得到补偿。

當復仇者未能讓做錯事的人感受到自己的感受時,同樣也無法被糾正。

Igualmente no se corrige cuando el vengador no logra hacerse sentir como tal ante quien ha cometido la injusticia.

Es bleibt ebenso ungesühnt, wenn der Rächer es versäumt, sich dem, der das Unrecht begangen hat, als solcher zu erkennen zu geben.

Воно також залишається невиправленим, коли мститель не в змозі дати зрозуміти, що він є таким для того, хто вчинив зло.

این ظلم همچنین زمانی جبران نشده است که انتقامجو نتواند خود را به عنوان چنین کسی به کسی که ظلم کرده است، احساس کند.

إنه غير مُعالج بنفس القدر عندما يفشل المنتقم في جعل نفسه محسوسًا كمنتقم لمن ارتكب الظلم.

Nó cũng không được sửa chữa khi kẻ báo thù không làm cho mình được cảm nhận như vậy đối với người đã làm điều sai.

İntikam alanın, yanlışı yapan kişiye kendini böyle hissettirmediği zaman da eşit şekilde düzeltilmemiştir.

Jest równie nie naprawione, gdy mściciel nie potrafi dać odczuć sprawcy, że jest nim.

It must be understood, that neither by word nor deed had I given Fortunato cause to doubt my good will.

آن|باید|باشد|فهمیده شود|که|نه|به وسیله|کلام|و نه|عمل|داشت|من|داده بودم|فورچوناتو|دلیلی|به|شک کردن|من|خوب|نیت

điều đó|phải|được|hiểu|rằng|không|bằng|lời|cũng không|hành động|đã|tôi|cho|Fortunato|lý do|để|nghi ngờ|thiện chí|tốt|ý chí

Це|має|бути|зрозуміло|що|ні|через|слово|ні|вчинок|мав|я|дав|Фортунато|причину|до|сумніву|моєї|доброї|волі

ذلك|يجب|أن يكون|مفهوم|أن|لا|بكلمة|كلمة|ولا|فعل|لم|أنا|أعط|فورتونات|سبب|إلى|يشك|نيتي|جيدة|إرادة

to|musi|być|zrozumiane|że|ani|przez|słowo|ani|czyn|nie miałem|ja|daną|Fortunato|powód|aby|wątpić|moją|dobrą|wolę

|||明白||既不|||||||给予||理由||怀疑|||

bu|-malı|-dir|anlaşılmalı|ki|ne|ile|söz|ne de|eylem|-mamıştım|ben|vermiş|Fortunato'ya|sebep|-e|şüphelenmek|benim|iyi|niyet

Es|muss|(hilfsverb)|verstanden|dass|weder|durch|Wort|noch|Tat|hatte|ich|gegeben|Fortunato|Grund|zu|zweifeln|meine|gute|Absicht

(eso)|debe|ser|entendido|que|ni|por|palabra|ni|hecho|había|yo|dado|fortunato|causa|a|dudar|mi|buena|voluntad

私がフォルトゥナートに私の善意を疑わせる理由を言葉でも行為でも与えなかったことを理解しなければなりません。

必须了解,我既没有言语也没有行动让福图纳托怀疑我的好意。

必須明白的是,無論是我的言語或行為,我都沒有讓福爾圖納託有理由懷疑我的善意。

Debe entenderse que ni con palabras ni con hechos había dado a Fortunato motivo para dudar de mi buena voluntad.

Es muss verstanden werden, dass ich Fortunato weder durch Wort noch durch Tat Anlass gegeben habe, an meinem guten Willen zu zweifeln.

Слід зрозуміти, що ні словом, ні ділом я не дав Фортунато підстав сумніватися в моїй добрій волі.

باید درک شود که نه به کلام و نه به عمل، من به فورتوناتو دلیلی برای شک در نیکخواهیام دادهام.

يجب أن يُفهم أنه لم يكن لدي، لا بالكلام ولا بالفعل، سبب لجعل فورتوناتوا يشك في حسن نيتي.

Cần phải hiểu rằng, tôi không bằng lời nói hay hành động đã khiến Fortunato nghi ngờ thiện chí của tôi.

Fortunato'ya iyi niyetimden şüphe etmesi için ne sözle ne de eylemle bir sebep vermediğimi anlamak gerekir.

Należy zrozumieć, że ani słowem, ani czynem nie dałem Fortunato powodu, by wątpił w moje dobre intencje.

I continued, as was my wont, to smile in his face, and he did not perceive that my smile now was at the thought of his immolation.

من|ادامه دادم|همانطور که|بود|من|عادت|به|لبخند|در|او|صورت|و|او|نکرد|نه|درک کرد|که|من|لبخند|اکنون|بود|به|آن|فکر|از|او|قربانی کردن

tôi|tiếp tục|như|đã|của tôi|thói quen|để|cười|vào|mặt anh ta|mặt|và|anh ta|không|không|nhận ra|rằng|nụ cười của tôi|nụ cười|bây giờ|đã|vào|ý nghĩ|ý nghĩ|về|sự|hy sinh

Я|продовжував|як|був|мій|звичай|до|усмішки|в|його|обличчя|і|він|не|не|помітив|що|моя|усмішка|тепер|була|над|думкою|думкою|про|його|жертву

|||||custom|||||||||||||||||||||immolation

أنا|استمريت|كما|كان|عادتي|عادة|أن|أبتسم|في|وجهه|وجهه|و|هو|لم|لا|يدرك|أن|ابتسامتي|ابتسامتي|الآن|كانت|عند|فكرة|فكرة|عن|حرقه|حرقه

ja|kontynuowałem|jak|było|moje|zwyczajem|do|uśmiechać się|w|jego|twarz|i|on|nie|nie|dostrzegał|że|mój|uśmiech|teraz|był|na|myślą|myśl|o|jego|ofiarowaniu

|继续||||习惯||微笑||||||||察觉到|||微笑||||||||献祭

ben|devam ettim|olarak|idi|benim|alışkanlığım|-meye|gülümsemek|içinde|onun|yüzü|ve|o|yaptı|değil|fark etti|ki|benim|gülümsemem|şimdi|idi|-e|düşünce|düşünce|-in|onun|kurban edilmesi

Ich|fuhr fort|wie|war|mein|Brauch|zu|lächeln|in|sein|Gesicht|und|er|tat|nicht|wahrnehmen|dass|mein|Lächeln|jetzt|war|über|den|Gedanken|an|sein|Opfer

yo|continué|como|era|mi|costumbre|a|sonreír|en|su|cara|y|él|no|no|percibió|que|mi|sonrisa|ahora|estaba|en|el|pensamiento|de|su|inmolación

私は、私の意志と同じように、彼の顔に微笑みかけ続けました、そして、彼は私の微笑みが今彼の犠牲を考えていることに気づいていませんでした。

我像往常一样继续微笑对他,他却没有注意到我此刻微笑的对象是他即将被牺牲的想法。

我繼續像往常一樣,對著他微笑,而他沒有意識到我現在的微笑是因為想到他的自焚。

Continué, como era mi costumbre, sonriendo en su cara, y él no percibió que mi sonrisa ahora era por el pensamiento de su inmolación.

Ich lächelte, wie es meine Art war, ihm ins Gesicht, und er bemerkte nicht, dass mein Lächeln jetzt dem Gedanken an seine Opferung galt.

Я продовжував, як зазвичай, усміхатися йому в обличчя, і він не помітив, що моя усмішка тепер була на думці про його жертву.

من به عادت همیشگیام به او لبخند زدم و او متوجه نشد که لبخند من اکنون به خاطر فکر قربانی کردن اوست.

واصلت، كما هو عادتي، الابتسام في وجهه، ولم يدرك أن ابتسامتي الآن كانت بفكرة تضحيته.

Tôi tiếp tục, như thường lệ, mỉm cười trước mặt anh ta, và anh ta không nhận ra rằng nụ cười của tôi bây giờ là vì suy nghĩ về sự hy sinh của anh ta.

Benim alışkanlığım olduğu gibi, yüzüne gülümsemeye devam ettim ve o, gülümsememin şimdi onun kurban edilmesi düşüncesiyle olduğunu fark etmedi.

Kontynuowałem, jak to miałem w zwyczaju, uśmiechać się do niego, a on nie dostrzegał, że mój uśmiech teraz był na myśl o jego ofierze.

He had a weak point - this Fortunato - although in other regards he was a man to be respected and even feared.

او|داشت|یک|ضعیف|نقطه|این|فورتوناتو|هرچند|در|دیگر|جنبه ها|او|بود|یک|مرد|به|بودن|مورد احترام|و|حتی|مورد ترس

anh ta|có|một|yếu|điểm|này|Fortunato|mặc dù|trong|những|khía cạnh|anh ta|là|một|người|để|được|tôn trọng|và|thậm chí|bị sợ hãi

Він|мав|один|слабкий|пункт|цей|Фортунато|хоча|в|інших|відношеннях|він|був|один|чоловік|щоб|бути|поважаним|і|навіть|боялися

هو|كان لديه|نقطة|ضعيفة|نقطة|هذا|فورتوناتوا|على الرغم من|في|أخرى|جوانب|هو|كان|رجلا|رجلا|أن|يكون|محترما|و|حتى|مخيفا

on|miał|jeden|słaby|punkt|ten|Fortunato|chociaż|w|innych|aspektach|on|był|człowiekiem|człowiekiem|do|być|szanowanym|i|nawet|budzącym strach

|||||||尽管|||方面|||||||尊敬||甚至|畏惧

o|sahipti|bir|zayıf|nokta|bu|Fortunato|rağmen|-de|diğer|yönlerden|o|idi|bir|adam|-e|olmak|saygı duyulan|ve|hatta|korkulan

Er|hatte|ein|schwacher|Punkt|dieser|Fortunato|obwohl|in|anderen|Belangen|er|war|ein|Mann|zu|sein|respektiert|und|sogar|gefürchtet

él|tenía|un|débil|punto|este|Fortunato|aunque|en|otros|aspectos|él|era|un|hombre|que|ser|respetado|y|hasta|temido

彼には弱点がありました-このFortunato-他の点では彼は尊敬され、恐れられる人でしたが。

他有一個弱點——這個福爾圖納托——儘管在其他方面他是一個值得尊敬甚至害怕的人。

Tenía un punto débil - este Fortunato - aunque en otros aspectos era un hombre a respetar e incluso temer.

Er hatte einen Schwachpunkt - dieser Fortunato - obwohl er in anderen Belangen ein Mann war, den man respektieren und sogar fürchten konnte.

У нього була слабка сторона - у цього Фортунато - хоча в інших відношеннях він був чоловіком, якого слід поважати і навіть боятися.

او یک نقطه ضعف داشت - این فورتوناتو - هرچند در سایر جنبهها مردی بود که باید به او احترام گذاشت و حتی از او ترسید.

كان لديه نقطة ضعف - هذا فورتوناتو - على الرغم من أنه في جوانب أخرى كان رجلاً يستحق الاحترام وحتى الخوف.

Anh ta có một điểm yếu - Fortunato này - mặc dù ở những khía cạnh khác, anh ta là một người đáng được tôn trọng và thậm chí là sợ hãi.

Bu Fortunato'nun zayıf bir noktası vardı - diğer yönlerden saygı duyulacak ve hatta korkulacak bir adamdı.

Miał słaby punkt - ten Fortunato - chociaż w innych aspektach był człowiekiem, którego należało szanować, a nawet się go bać.

He prided himself on his connoisseurship in wine.

او|افتخار کرد|به خود|به|او|شناخت|در|شراب

anh ta|tự hào|bản thân anh ta|về|sự|am hiểu|trong|rượu

Він|пишався|собою|на|його|знання|в|вині

|||||knowledge||

هو|افتخر|بنفسه|على|معرفته|خبرته|في|النبيذ

on|szczycił|się|na|jego|znawstwie|w|winie

|以...自豪||||鉴赏力||葡萄酒

o|gururlandı|kendisi|-e|onun|uzmanlığı|-de|şarap

Er|rühmte|sich|auf|sein|Kennerwissen|in|Wein

él|se enorgulleció|a sí mismo|de|su|conocimiento experto|en|vino

彼はワインの愛好家であることに誇りを持っていた。

他對自己的葡萄酒鑑賞力感到自豪。

Se enorgullecía de su conocimiento en vinos.

Er war stolz auf sein Wissen über Wein.

Він пишався своїм знанням вин.

او به دانش خود در زمینه شراب افتخار میکرد.

كان يفتخر بمعرفته في النبيذ.

Anh ta tự hào về sự am hiểu của mình về rượu.

Şarap konusundaki uzmanlığıyla gurur duyuyordu.

Dumał się ze swojego znawstwa win.

Few Italians have the true virtuoso spirit.

کمی|ایتالیایی ها|دارند|آن|واقعی|ویروتوزو|روح

ít|người Ý|có|tinh thần|thực sự|nghệ sĩ|tinh thần

Небагато|італійців|мають|той|справжній|віртуозний|дух

|||||virtuoso|

قليل من|الإيطاليين|لديهم|الروح|الحقيقية|الفيرتوزو|الروح

nieliczni|Włosi|mają|tego|prawdziwego|wirtuoza|ducha

||||真正的|艺术大师|精神

az sayıda|İtalyanlar|sahip|gerçek|gerçek|virtuoz|ruhu

Wenige|Italiener|haben|den|wahren|Virtuosen|Geist

pocos|italianos|tienen|el|verdadero|virtuoso|espíritu

真の名手精神を持っているイタリア人はほとんどいません。

很少有義大利人擁有真正的大師精神。

Pocos italianos tienen el verdadero espíritu virtuoso.

Wenige Italiener haben den wahren Virtuosengeist.

Лише кілька італійців мають справжній віртуозний дух.

تعداد کمی از ایتالیاییها روحیه واقعی ویولتویست را دارند.

قليل من الإيطاليين لديهم روح العازف الحقيقي.

Ít người Ý có được tinh thần nghệ sĩ thực thụ.

Az sayıda İtalyan gerçek virtuoz ruhuna sahiptir.

Niewielu Włochów ma prawdziwego wirtuoza ducha.

For the most part their enthusiasm is adopted to suit the time and opportunity - to practice imposture upon the British and Austrian millionaires.

برای|(حرف تعریف)|بیشتر|بخش|آنها|اشتیاق|است|پذیرفته شده|به|مناسب کردن|(حرف تعریف)|زمان|و|فرصت|برای|عمل کردن|فریبکاری|بر|(حرف تعریف)|بریتانیایی|و|اتریشی|میلیونرها

cho|phần lớn|nhất|phần|sự|nhiệt tình|thì|được chấp nhận|để|phù hợp|thời gian|thời gian|và|cơ hội|để|thực hành|sự giả mạo|trên|những|người Anh|và|người Áo|triệu phú

Для|найбільш|більш|частини|їхній|ентузіазм|є|адаптований|щоб|відповідати|часу|часу|і|можливості|щоб|практикувати|обман|над|британськими|британськими|і|австрійськими|мільйонерами

||||||||||||||||imposture||||||

من أجل|الأكثر|معظم|جزء|حماسهم|حماس|هو|مُعتمد|ل|يناسب|الوقت|الفرصة|و|الفرصة|ل|ممارسة|خداع|على|ال|البريطانيين|و|النمساويين|الملايين

dla|największej|większości|części|ich|entuzjazm|jest|przyjęty|aby|dostosować|czas|i|oraz|okazję|aby|praktykować|oszustwo|na|brytyjskich|i|oraz|austriackich|milionerach

|||||热情||||||||机会||行骗|欺骗行为|对...进行||||奥地利的|百万富翁

için|en|çoğu|kısım|onların|coşku|dır|benimsenmiştir|-mek için|uymak|en|zaman|ve|fırsat|-mek için|uygulamak|dolandırıcılık|üzerine|en|Britanyalı|ve|Avusturyalı|milyonerler

Für|die|meisten|Teil|ihr|Enthusiasmus|ist|angepasst|um|zu passen|die|Zeit|und|Gelegenheit|um|zu praktizieren|Betrug|gegenüber|den|britischen|und|österreichischen|Millionären

para|la|la mayor|parte|su|entusiasmo|es|adoptado|para|adaptarse|el|tiempo|y|oportunidad|para|practicar|impostura|sobre|los|británicos|y|austriacos|millonarios

ほとんどの場合、彼らの熱意は時間と機会に合うように採用されています-英国とオーストリアの百万長者に強迫観念を実践することです。

По большей части их энтузиазм используется в соответствии со временем и возможностью - обманывать британских и австрийских миллионеров.

大多數情況下,他們的熱情是為了適應時間和機會——欺騙英國和奧地利的百萬富翁。

En su mayor parte, su entusiasmo se adapta para adecuarse al tiempo y la oportunidad - para practicar la impostura sobre los millonarios británicos y austriacos.

In der Regel ist ihr Enthusiasmus angepasst, um der Zeit und Gelegenheit zu entsprechen - um Betrug an den britischen und österreichischen Millionären zu üben.

В основному їхній ентузіазм адаптується відповідно до часу та можливостей - щоб обманювати британських та австрійських мільйонерів.

در بیشتر موارد، اشتیاق آنها به گونهای تنظیم شده است که با زمان و فرصت سازگار باشد - تا بر روی میلیونرهای بریتانیایی و اتریشی تقلب کنند.

في الغالب، يتم تبني حماسهم ليتناسب مع الوقت والفرصة - لممارسة الخداع على الأثرياء البريطانيين والنمساويين.

Về phần lớn, sự nhiệt tình của họ được điều chỉnh để phù hợp với thời gian và cơ hội - để thực hiện sự giả dối đối với các triệu phú Anh và Áo.

Çoğunlukla, coşkuları zaman ve fırsata uygun hale getirilmiştir - Britanyalı ve Avusturyalı milyonerler üzerinde dolandırıcılık yapmak için.

Przede wszystkim ich entuzjazm jest dostosowywany do czasu i okazji - aby oszukiwać brytyjskich i austriackich milionerów.

In painting and gemmary, Fortunato, like his countrymen , was a quack - but in the matter of old wines he was sincere.

در|نقاشی|و|جواهرشناسی|فورتوناتو|مانند|او|هموطنان|بود|یک|شارلاتان|اما|در|موضوع|موضوع|از|قدیمی|شراب ها|او|بود|صادق

trong|hội họa|và|ngọc học|Fortunato|như|những|đồng hương|thì|một|kẻ giả mạo|nhưng|trong|vấn đề|vấn đề|của|cũ|rượu|ông ấy|thì|chân thành

У|живописі|і|геммології|Фортунато|як|його|співвітчизники|був|одним|шарлатаном|але|у|питаннях|справі|старих|старих|винах|він|був|щирим

|||gemology|||||||quack||||||||||

في|الرسم|و|علم الأحجار الكريمة|فورتونات|مثل|بلده|مواطنيه|كان|واحد|دجال|لكن|في|موضوع|الأمر|من|قديمة|نبيذ|هو|كان|مخلص

w|malarstwie|oraz|jubilerstwie|Fortunato|jak|jego|rodacy|był|a|oszustem|ale|w|kwestii|starych||win|winach|on|był|szczery

|绘画||宝石鉴定||||同胞们|||江湖骗子|||||||老酒|||真诚的

-de|resim yapma|ve|taş işçiliği|Fortunato|gibi|onun|hemşehrileri|dı|bir|sahtekar|ama|-de|en|konuda|-in|eski|şaraplar|o|dı|samimi

In|Malerei|und|Gemmologie|Fortunato|wie|seine|Landsleute|war|ein|Scharlatan|aber|in|der|Angelegenheit|von|alten|Weinen|er|war|aufrichtig

en|pintura|y|gemología|Fortunato|como|sus|compatriotas|era|un|charlatán|pero|en|el|asunto|de|viejos|vinos|él|estaba|sincero

絵画と宝石では、フォルトゥナートは彼の同胞のように、いんちきでした-しかし、古いワインに関しては、彼は誠実でした。

在繪畫和寶石方面,福爾圖納托和他的同胞一樣,是個庸醫,但在陳年葡萄酒方面,他是真誠的。

En pintura y gemología, Fortunato, como sus compatriotas, era un charlatán - pero en lo que respecta a los vinos viejos, era sincero.

In der Malerei und der Edelsteinbearbeitung war Fortunato, wie seine Landsleute, ein Scharlatan - aber in Bezug auf alte Weine war er aufrichtig.

У живопису та геммології Фортунато, як і його співвітчизники, був шарлатаном - але в питаннях старих вин він був щирим.

در نقاشی و جواهرسازی، فورتوناتو، مانند هموطنانش، یک شارلاتان بود - اما در مورد شرابهای قدیمی او صادق بود.

في الرسم وصناعة الأحجار الكريمة، كان فورتوناتو، مثل مواطنيه، دجالًا - لكن في مسألة النبيذ القديم كان صادقًا.

Trong hội họa và đá quý, Fortunato, giống như những người đồng hương của anh, là một kẻ lừa đảo - nhưng trong vấn đề rượu vang cổ, anh ta là người chân thành.

Resim ve değerli taşlar konusunda Fortunato, kendi ülke insanları gibi bir dolandırıcıydı - ama eski şaraplar meselesinde samimiydi.

W malarstwie i jubilerstwie Fortunato, jak jego rodacy, był oszustem - ale w kwestii starych win był szczery.

In this respect I did not differ from him materially : I was skilful in the Italian vintages myself, and bought largely whenever I could.

در|این|زمینه|من|نکردم|نه|تفاوت|از|او|به طور مادی|من|بود|ماهر|در|آن|ایتالیایی|سالهای تولید شراب|خودم|و|خریدم|به مقدار زیاد|هر زمان|من|میتوانستم

trong|điều này|khía cạnh|tôi|đã|không|khác|với|ông ấy|về mặt vật chất|tôi|thì|khéo léo|trong|những|Ý|vụ thu hoạch rượu|bản thân tôi|và|đã mua|nhiều|bất cứ khi nào|tôi|có thể

У|цьому|відношенні|я|не||відрізнявся|від|нього|матеріально|я|був|досвідчений|у|в|італійських|вина|сам|і|купував|великими обсягами|коли|я|міг

||||||||||||||||vintages|||||||

في|هذا|الصدد|أنا|لم|لا|أختلف|عن|هو|مادياً|أنا|كنت|بارع|في|ال|الإيطالية|النبيذ|بنفسي|و|اشتريت|بكميات كبيرة|كلما|أنا|استطعت

w|tej|kwestii|ja|nie|nie|różniłem|od|niego|zasadniczo|ja|byłem|biegły|w|włoskich|||sam|oraz|kupowałem|w dużych ilościach|kiedykolwiek|ja|mogłem

||在这方面||||不同意|||实质上|||熟练的||||葡萄酒酿造|我自己||购买了|大量地|每当||

-de|bu|açıdan|ben|yapmadım|-i|farklılık göstermek|-den|ona|maddi olarak|ben|dım|yetenekli|-de|en|İtalyan|şarapları|kendim|ve|satın aldım|büyük ölçüde|her zaman|ben|yapabildim

In|diesem|Punkt|ich|tat|nicht|unterschied|von|ihm|materiell|ich|war|geschickt|in|den|italienischen|Jahrgängen|selbst|und|kaufte|großenteils|wann immer|ich|konnte

en|este|respecto|yo|(verbo auxiliar)|no|diferir|de|él|materialmente|yo|estaba|hábil|en|los|italianos|cosechas|yo mismo|y|compré|en gran cantidad|siempre que|yo|podía

この点で、私は彼と実質的に違いはありませんでした。私はイタリアのヴィンテージに精通しており、可能な限り主に購入しました。

在這方面,我與他並沒有本質上的不同:我自己對義大利葡萄酒很熟悉,只要有可能,我就會大量購買。

En este aspecto no difería materialmente de él: yo también era hábil en las cosechas italianas y compraba en grandes cantidades siempre que podía.

In dieser Hinsicht unterschied ich mich nicht wesentlich von ihm: Ich war selbst versiert in den italienischen Jahrgängen und kaufte großzügig, wann immer ich konnte.

У цьому відношенні я суттєво не відрізнявся від нього: я сам був досвідченим у італійських винах і купував їх у великих кількостях, коли тільки міг.

در این مورد من از او به طور اساسی متفاوت نبودم: من خودم در شرابهای ایتالیایی ماهر بودم و هر زمان که میتوانستم به مقدار زیاد خرید میکردم.

في هذا الصدد، لم أختلف عنه بشكل كبير: كنت بارعًا في النبيذ الإيطالي بنفسي، وكنت أشتري بكثرة كلما استطعت.

Về mặt này, tôi không khác biệt nhiều so với anh ta: tôi cũng có kỹ năng trong các loại rượu vang Ý, và mua sắm nhiều khi có thể.

Bu bakımdan ondan önemli ölçüde farklı değildim: İtalyan şarapları konusunda kendim de yetenekliydim ve ne zaman mümkünse büyük miktarlarda alım yapıyordum.

Pod tym względem nie różniłem się od niego materialnie: sam byłem biegły w włoskich winach i kupowałem w dużych ilościach, kiedy tylko mogłem.

It was about dusk, one evening during the supreme madness of the carnival season, that I encountered my friend.

آن|بود|در حدود|غروب|یک|عصر|در حین|آن|شدیدترین|جنون|ِ|آن|کارناوال|فصل|که|من|ملاقات کردم|ِ من|دوست

điều đó|thì|khoảng|chạng vạng|một|buổi tối|trong suốt|sự|tối cao|điên cuồng|của|lễ hội|lễ hội|mùa|rằng|tôi|đã gặp|bạn|bạn

Це|було|близько|сутінок|один|вечір|під час|найвищого|найвищого|божевілля|карнавального|сезону|карнавального|сезону|що|я|зустрів|мого|друга

ذلك|كان|حوالي|الغسق|واحدة|مساء|خلال|ال|القصوى|جنون|من|ال|الكرنفال|موسم|الذي|أنا|قابلت|صديقي|صديقي

to|było|około|zmierzchu|pewnego|wieczoru|w trakcie|szalonej|szaleństwa|szaleństwa|karnawału|sezonu|karnawałowego|że|że|ja|spotkałem|mojego|przyjaciela

|||黄昏时分|||||至高无上的|狂欢季的疯狂|||狂欢节|狂欢节期间|||||

bu|dı|civarında|alacakaranlık|bir|akşam|sırasında|en|zirve|delilik|-in|en|karnaval|sezon|ki|ben|karşılaştım|benim|arkadaşım

Es|war|gegen|Dämmerung|eines|Abends|während|der|höchsten|Wahnsinn|des||Karnevals|Saison|dass|ich|traf|meinen|Freund

fue|acerca|del|anochecer|una|tarde|durante|la|suprema|locura|del|el|carnaval|temporada|que|yo|encontré|mi|amigo

カーニバルシーズンの最高の狂気のある夜、私が友人に出会ったのは夕暮れの頃でした。

黃昏時分,在嘉年華最瘋狂的一個晚上,我遇到了我的朋友。

Era alrededor del anochecer, una noche durante la suprema locura de la temporada de carnaval, que encontré a mi amigo.

Es war gegen Dämmerung, an einem Abend während des höchsten Wahnsinns der Karnevalszeit, dass ich meinen Freund traf.

Це було близько сутінків, одного вечора під час безумства карнавального сезону, коли я зустрів свого друга.

این موضوع در غروب یکی از شبها در اوج جنون فصل کارناوال بود که با دوستم برخورد کردم.

كان ذلك حوالي الغسق، في إحدى الأمسيات خلال جنون موسم الكرنفال، عندما قابلت صديقي.

Vào khoảng chạng vạng, một buổi tối trong cơn điên cuồng tột độ của mùa lễ hội, tôi đã gặp người bạn của mình.

Bir akşam, karnaval sezonunun en çılgın döneminde, arkadaşım ile karşılaştım.

To było około zmierzchu, pewnego wieczoru podczas szaleństwa sezonu karnawałowego, kiedy spotkałem mojego przyjaciela.

He accosted me with excessive warmth, for he had been drinking much.

او|نزدیک شد|به من|با|بیش از حد|گرمی|زیرا|او|داشت|بوده|نوشیدن|زیاد

anh ấy|đã tiếp cận|tôi|với|quá mức|sự ấm áp|vì|anh ấy|đã|đã|uống|nhiều

Він|підійшов|до мене|з|надмірною|теплотою|бо|він|мав|був|пив|багато

|approached||||||||||

هو|اقترب|مني|مع|مفرط|حفاوة|لأن|هو|كان|قد|يشرب|كثيرًا

on|zaczepił|mnie|z|nadmierną|serdecznością|ponieważ|on|pił|był|pijąc|dużo

|纠缠|||过分的|热情||||一直在||很多

o|yaklaştı|bana|ile|aşırı|sıcaklık|çünkü|o|içmişti|olmuştu|içmekte|çok

Er|sprach an|mich|mit|übermäßiger|Wärme|denn|er|hatte|gewesen|Trinken|viel

él|se acercó a|mí|con|excesiva|calidez|porque|él|había|estado|bebiendo|mucho

彼はたくさん飲んでいたので、私に過度の暖かさを与えてくれました。

他對我的態度非常熱情,因為他喝了很多酒。

Él me abordó con excesivo calor, pues había estado bebiendo mucho.

Er sprach mich mit übermäßiger Herzlichkeit an, denn er hatte viel getrunken.

Він підійшов до мене з надмірною теплотою, адже він багато пив.

او با گرمی بیش از حد به من نزدیک شد، زیرا او خیلی نوشیده بود.

لقد اقترب مني بحرارة مفرطة، لأنه كان قد شرب كثيرًا.

Ông ta đã chào tôi với sự nồng nhiệt thái quá, vì ông ta đã uống rất nhiều.

Bana aşırı bir sıcaklıkla yaklaştı, çünkü çok içki içmişti.

Zaczepił mnie z nadmierną serdecznością, ponieważ dużo pił.

The man wore motley.

مرد|مرد|پوشید|لباس رنگارنگ

người|đàn ông|đã mặc|trang phục nhiều màu

Чоловік|чоловік|носив|строкатий одяг

|||a multicolored fabric

الرجل|رجل|ارتدى|ملابس ملونة

ten|mężczyzna|nosił|wielobarwny strój

|||五颜六色的衣服

o|adam|giyiyordu|alacalı

Der|Mann|trug|bunte Kleidung

el|hombre|llevaba|un traje de colores

男は雑多な服を着ていた。

那人穿著雜色衣服。

El hombre llevaba un disfraz de arlequín.

Der Mann trug einen bunten Anzug.

Чоловік був одягнений у строкатий костюм.

مرد لباس رنگارنگی پوشیده بود.

كان الرجل يرتدي ملابس ملونة.

Người đàn ông mặc trang phục sặc sỡ.

Adam çok renkli giysiler giyiyordu.

Mężczyzna był ubrany w wielobarwne szaty.

He had on a tightly-fitting party-striped dress, and his head was surmounted by the conical cap and bells.

او|داشت|پوشیده بود|یک|||||لباس|و|او|سر|بود|بر روی|توسط|آن|مخروطی|کلاه|و|زنگ ها

anh ấy|đã|mặc|một|||||váy|và|đầu của anh ấy|đầu|đã|được đội|bởi|cái|hình chóp|mũ|và|chuông

Він|мав|на|одне|||||плаття|і|його|голова|була|увінчана|з|конусною|конусною|шапкою|і|дзвіночками

|||||||||||||topped||||||

هو|كان لديه|يرتدي|فستان|||||فستان|و|رأسه|رأسه|كان|متوج|ب|القبعة|مخروطية|قبعة|و|أجراس

on|miał|na sobie|sukienkę||||||i|jego|głowa|była|zwieńczona|przez|stożkowy||czapkę|i|dzwonki

||||紧紧地|紧身的||条纹的||||头部||顶着|||锥形的|||铃铛帽

o|giymişti|üzerinde|bir|sıkı|sıkı||çizgili|elbise|ve|onun|başı|idi|taçlandırılmış|ile|o|konik|şapka|ve|çanlar

Er|hatte|an|ein|||||Kleid|und|sein|Kopf|war|gekrönt|von|der|konischen|Mütze|und|Glöckchen

él|llevaba|puesto|un|||||vestido|y|su|cabeza|estaba|coronada|por|el|cónico|gorro|y|campanas

他穿著一件緊身的派對條紋連身裙,頭上戴著圓錐形帽子和鈴鐺。

Tenía puesto un vestido de rayas ajustado, y su cabeza estaba coronada por un gorro cónico y campanas.

Er hatte ein eng anliegendes, gestreiftes Festkleid an, und sein Kopf war mit einer konischen Mütze und Glocken geschmückt.

На ньому була облягаюча сукня в смужку, а на голові - конусоподібна шапка з дзвіночками.

او یک لباس تنگ با نوارهای رنگی به تن داشت و سرش با کلاهی مخروطی و زنگها تزئین شده بود.

كان يرتدي فستانًا ضيقًا مخططًا، وكان رأسه مزينًا بقبعة مخروطية وأجراس.

Ông ta mặc một bộ váy kẻ sọc chật chội, và đầu ông ta đội một chiếc mũ hình nón có chuông.

Üzerinde sıkı bir şekilde oturan parti çizgili bir elbise vardı ve başında konik bir şapka ile çanlar vardı.

Miał na sobie ciasno dopasowaną suknię w paski, a na głowie nosił stożkowatą czapkę z dzwonkami.

I was so pleased to see him, that I thought I should never have done wringing his hand.

من|بود|خیلی|خوشحال|به|دیدن|او|که|من|فکر کردم|من|باید|هرگز|داشته باشم|انجام دادن|فشردن|او|دست

tôi|đã|rất|vui mừng|để|thấy|anh ấy|đến nỗi|tôi|đã nghĩ|tôi|sẽ|không bao giờ|đã|làm|siết chặt|tay của anh ấy|tay

Я|був|так|радий|до|побачити|його|що|я|думав|я|повинен|ніколи|мав|закінчити|стиснення|його|руки

|||||||||||||||wringing||

أنا|كنت|جدًا|سعيد|أن|أرى|هو|أن|أنا|اعتقدت|أنا|سوف|أبدًا|أن|أفعل|عصر|يده|يد

ja|byłem|tak|zadowolony|z|zobaczyć|go|że|ja|myślałem|ja|powinienem|nigdy|mieć|zrobić|ściskając|jego|dłoń

|||高兴|||||||||||停下|握手不放||

ben|idim|o kadar|memnun|-mek|görmek|onu|o kadar ki|ben|düşündüm|ben|-meliyim|asla|-mek|yapmış|sıkarak|onun|eli

Ich|war|so|erfreut|zu|sehen|ihn|dass|ich|dachte|ich|sollte|niemals|haben|getan|drücken|seine|Hand

yo|estaba|tan|contento|a|ver|él|que|yo|pensé|yo|debería|nunca|haber|terminado|retorciendo|su|mano

我见到他感到非常高兴,以至于我觉得我永远都不会停止握着他的手。

我很高興見到他,我想我根本不該扭動他的手。

Estaba tan contento de verlo, que pensé que nunca terminaría de estrechar su mano.

Ich war so erfreut, ihn zu sehen, dass ich dachte, ich würde nie aufhören, ihm die Hand zu schütteln.

Я був так радий його бачити, що думав, що ніколи не перестану тиснути йому руку.

من آنقدر از دیدن او خوشحال شدم که فکر کردم هرگز دستش را رها نخواهم کرد.

كنت سعيدًا جدًا لرؤيته، لدرجة أنني ظننت أنني لن أتوقف عن مصافحته.

Tôi vui mừng đến nỗi nghĩ rằng mình sẽ không bao giờ ngừng bắt tay ông.

Onu görmekten o kadar memnun oldum ki, elini sıkmayı asla bırakmayacakmışım gibi düşündüm.

Byłem tak zadowolony, że go zobaczyłem, że myślałem, że nigdy nie przestanę mu ściskać ręki.

I said to him, "My dear Fortunato, you are luckily met.

من|گفتم|به|او|من|عزیز|فورتوناتو|تو|هستی|به طرز خوششانسی|ملاقات شده

tôi|đã nói|với|anh ấy|của tôi|thân mến|Fortunato|bạn|thì|một cách may mắn|gặp

Я|сказав|до|йому|Мій|дорогий|Фортунато|ти|є|щасливо|зустрілися

أنا|قلت|إلى|له|عزيزي|العزيز|فورتوناتو|أنت|تكون|لحسن الحظ|قابلت

ja|powiedziałem|do|niego|mój|drogi|Fortunato|ty|jesteś|szczęśliwie|spotkany

ben|söyledim|-e|ona|benim|sevgili|Fortunato|sen|-sin|şans eseri|karşılaştın

Ich|sagte|zu|ihm|Mein|lieber|Fortunato|du|bist|glücklicherweise|getroffen

yo|dije|a|él|mi|querido|Fortunato|tú|estás|afortunadamente|encontrado

我对他说:“我亲爱的福图纳托,你真是幸运相逢。

我對他說:「親愛的福爾圖納托,很幸運能遇見你。

Le dije: "Mi querido Fortunato, qué suerte encontrarte.

Ich sagte zu ihm: "Mein lieber Fortunato, du bist glücklicherweise getroffen.

Я сказав йому: "Мій дорогий Фортунато, ти щасливо зустрівся."

به او گفتم: "دوست عزیزم فورچوناتو، خوش شانس ملاقات کردیم.

قلت له، "عزيزي فورتوناتو، لقد التقيت بك محظوظًا.

Tôi đã nói với anh ấy, "Người bạn thân mến của tôi, Fortunato, thật may mắn khi gặp anh."

Ona, "Sevgili Fortunato, ne şanslı bir karşılaşma!" dedim.

Powiedziałem do niego: "Mój drogi Fortunato, spotkałeś mnie w dobrym momencie.

How remarkably well you are looking today!

چقدر|به طرز شگفت انگیزی|خوب|تو|هستی|به نظر میرسی|امروز

như thế nào|đáng kinh ngạc|tốt|bạn|thì|đang nhìn|

Як|надзвичайно|добре|ти|виглядаєш|виглядаєш|сьогодні

كم|بشكل ملحوظ|جيد|أنت|تكون|تبدو|اليوم

jak|niezwykle|dobrze|ty|jesteś|wyglądasz|dzisiaj

|非常|||||

ne kadar|dikkate değer|iyi|sen|-sin|görünüyorsun|bugün

Wie|bemerkenswert|gut|du|bist|aussiehst|heute

|notablemente|bien||||hoy

你今天看起来非常健康!"

你今天看起來多麼氣色啊!

¡Qué bien te ves hoy!

Wie bemerkenswert gut siehst du heute aus!

Як ти дивовижно виглядаєш сьогодні!

چقدر امروز خوب به نظر میرسی!

كم أنك تبدو رائعًا اليوم!

Hôm nay anh trông thật tuyệt vời!

Bugün ne kadar iyi görünüyorsun!

Jak wspaniale dzisiaj wyglądasz!

But I have received a pipe of what passes for Amontillado, and I have my doubts."

اما|من|دارم|دریافت کرده ام|یک|لوله|از|آنچه|عبور می کند|به عنوان|آمانتیلادو|و|من|دارم|من|شک ها

nhưng|tôi|có|đã nhận|một|thùng|của|cái gì|được coi|là|Amontillado|và|tôi|có|của tôi|nghi ngờ

Але|я|маю|отримав|один|бочонок|з|те що|проходить|за|Амонтильядо|і|я|маю|свої|сумніви

لكن|أنا|لدي|استلمت|أنبوب|أنبوب|من|ما|يمر|ك|أمونتيلا|و|أنا|لدي|شكوكي|شكوكي

ale|ja|mam|otrzymałem|jedną|beczkę|z|co|uchodzi|za|Amontillado|i|ja|mam|moje|wątpliwości

|||收到了||一桶酒|||冒充||雪莉酒|||||怀疑

ama|ben|sahipim|aldım|bir|fıçı|-den|ne|geçiyor|olarak|Amontillado|ve|ben|sahipim|benim|şüphelerim

Aber|ich|habe|erhalten|ein|Rohr|von|was|gilt|als|Amontillado|und|ich|habe|meine|Zweifel

pero|yo|he recibido|recibido|un|barril|de|lo que|pasa|por|Amontillado|y|yo|tengo|mis|dudas

但我收到了一管冒充阿蒙蒂亞多的酒,我對此表示懷疑。”

Pero he recibido un barril de lo que se hace pasar por Amontillado, y tengo mis dudas."

Aber ich habe ein Fass von dem erhalten, was für Amontillado gilt, und ich habe meine Zweifel."

Але я отримав бочку того, що називають Амонтильядо, і я маю свої сумніви."

اما من یک لوله از چیزی که به عنوان آمنتیدو شناخته میشود دریافت کردهام و شک دارم."

لكنني تلقيت أنبوبًا مما يُعتبر أمانتيلا، ولدي شكوكي."

Nhưng tôi đã nhận được một thùng rượu mà người ta gọi là Amontillado, và tôi có những nghi ngờ."

Ama Amontillado olarak geçen bir fıçı aldım ve şüphelerim var."

Ale otrzymałem beczkę tego, co uchodzi za Amontillado, i mam swoje wątpliwości."

"How ?"

چگونه

như thế nào

Як

كيف

jak

nasıl

Wie

cómo

"¿Cómo ?"

"Wie?"

"Як ?"

"چطور؟"

"كيف؟"

"Cái gì ?"

"Nasıl?"

"Jak?"

said he.

گفت|او

nói|anh ấy

сказав|він

قال|هو

powiedział|on

söyledi|o

sagte|er

dijo|él

dijo él.

sagte er.

сказав він.

گفت او.

قال.

ông ấy nói.

dedi.

powiedział.

"Amontillado ?

آمونتیادو

Amontillado

Амонтильядо

Amontillado

أمونتيلادو

Amontillado

阿蒙蒂亚多

Amontillado

Amontilhado

amontillado

"¿Amontillado?

"Amontillado ?

"Амонтільядо ?

"آمونتیلادو؟

"أمونتيلادو؟

"Amontillado ?

"Amontillado mu?

"Amontillado ?

A pipe ?

یک|لوله

một|ống

Трубка|труба

|pipe

أن|أنبوب

rura|rura

|管子?

bir|boru

Ein|Rohr

una|tubería

¿Una tubería?

Eine Pfeife ?

Трубка ?

یک لوله؟

أنبوب؟

Một ống ?

Bir boru mu?

Rura ?

Impossible !

غیرممکن

không thể

Неможливо

مستحيل

niemożliwe

不可能!

imkansız

Unmöglich

¡imposible

¡Imposible!

Unmöglich !

Неможливо !

غیرممکن!

مستحيل!

Không thể nào !

İmkansız!

Niemożliwe !

And in the middle of the carnival!"

و|در||وسط|||کارناوال

và|ở|cái|giữa|của|lễ hội|lễ hội

І|в||середині|карнавалі||

و|في|ال|منتصف|من|ال|الكرنفال

i|w|środku||||karnawału

|||中间|||狂欢节中间

ve|içinde|-i|ortası|-in|-i|karnaval

Und|in|dem|Mittelpunkt|von|dem|Karneval

y|en|el|medio|del|el|carnaval

¡Y en medio del carnaval!"

Und mitten im Karneval!"

"І посеред карнавалу!"

و در وسط کارناوال!

"وفي وسط الكرنفال!"

"Và ngay giữa lễ hội!"

Ve karnavalın ortasında!

A w środku karnawału!

"I have my doubts," I replied; "and I was silly enough to pay the full Amontillado price without consulting you in the matter.

من|دارم|من|شک|من|پاسخ داد|و|من|بود|احمق|به اندازه کافی|که|پرداخت کنم|آن|کامل|آمانتیلادو|قیمت|بدون|مشورت کردن|شما|در|آن|موضوع

tôi|có|những|nghi ngờ|tôi|trả lời|và|tôi|đã|ngốc|đủ|để|trả|cái|đầy đủ|Amontillado|giá|không|tham khảo|bạn|trong|vấn đề|vấn đề

Я|маю|свої|сумніви|Я|відповів|і|Я|був|дурний|достатньо|щоб|заплатити|повну|повну|Амонтильядо|ціну|без|консультації|тебе|в|цій|справі

أنا|لدي|مشكوكي|الشكوك|أنا|أجبت|و|أنا|كنت|ساذج|بما فيه الكفاية|أن|أدفع|ال|كامل|أمونتيلا|الثمن|دون|استشارتك|أنت|في|المسألة|

|||||respondi|||||||||||||||||

ja|mam|moje|wątpliwości|ja|odpowiedziałem|i|ja|byłem|głupi|wystarczająco|aby|zapłacić|pełną||Amontillado|cenę|bez|konsultowania|ciebie|w|tej|sprawie

|||疑虑||||||愚蠢的|足够|||||雪莉酒|价格|没有咨询|咨询||||这件事

ben|sahipim|benim|şüphelerim|ben|yanıtladım|ve|ben|-dım|aptal|kadar|-mek|ödemek|-i|tam|Amontillado|fiyat|-madan|danışmak|sana|-de|-i|konu

Ich|habe|meine|Zweifel|Ich|antwortete|und|Ich|war|dumm|genug|zu|zahlen|den|vollen|Amontillado|Preis|ohne|zu konsultieren|dich|in|der|Angelegenheit

yo|tengo|mis|dudas|yo|respondí|y|yo|estaba|tonto|suficiente|para|pagar|el|completo|Amontillado|precio|sin|consultar|contigo|en|el|asunto

「我有疑問,」我回答。 「我太愚蠢了,在沒有諮詢你此事的情況下就支付了阿蒙蒂拉多的全部價格。

"Tengo mis dudas," respondí; "y fui lo suficientemente tonto como para pagar el precio completo del Amontillado sin consultarte sobre el asunto.

"Ich habe meine Zweifel," antwortete ich; "und ich war dumm genug, den vollen Amontillado-Preis zu zahlen, ohne dich in dieser Angelegenheit zu konsultieren.

"У мене є сумніви," - відповів я; "і я був досить дурний, щоб заплатити повну ціну за Амонтильядо, не проконсультувавшись з тобою з цього питання.

"من شک دارم،" من پاسخ دادم؛ "و من آنقدر احمق بودم که قیمت کامل آمانتیلا را بدون مشورت با تو پرداخت کردم.

"لدي شكوكي،" أجبت؛ "وكان من السخيف أن أدفع ثمن الأمانتيجادو بالكامل دون استشارتك في الأمر.

"Tôi có những nghi ngờ," tôi trả lời; "và tôi đã ngu ngốc khi trả giá đầy đủ cho Amontillado mà không tham khảo ý kiến của bạn về vấn đề này.

"Şüphelerim var," diye yanıtladım; "ve bu konuda seninle danışmadan tam Amontillado fiyatını ödeyecek kadar aptaldım.

"Mam swoje wątpliwości," odpowiedziałem; "i byłem na tyle głupi, że zapłaciłem pełną cenę Amontillado, nie konsultując się z tobą w tej sprawie.

You were not to be found, and I was fearful of losing a bargain."

تو|بودی|نه|به|پیدا|یافت|و|من|بودم|ترسان|از|از دست دادن|یک|معامله

bạn|đã|không|để|bị|tìm thấy|và|tôi|đã|sợ|về|mất|một|món hời

Ти|був|не|повинен|бути|знайдений|і|Я|був|боявся|втратити|втрату|угоду|угоду

أنت|كنت|لا|أن|تكون|موجود|و|أنا|كنت|خائف|من|فقدان|صفقة|صفقة

ty|byłeś|nie|miało|być|znaleziony|i|ja|byłem|obawiający się|o|utratę|okazji|okazji

|||||||||担心||失去||便宜货

sen|-dın|değil|-mek|olmak|bulunmak|ve|ben|-dım|korkuyordum|-den|kaybetmek|bir|fırsat

Du|warst|nicht|zu|sein|finden|und|ich|war|ängstlich|vor|verlieren|ein|Schnäppchen

tú|estabas|no|que|estar|encontrado|y|yo|estaba|temeroso|de|perder|un|trato

找不到你,我害怕失去便宜貨。”

No podías ser encontrado, y temía perder una oportunidad.

Du warst nicht zu finden, und ich hatte Angst, ein Geschäft zu verlieren."

Тебе не було, і я боявся втратити вигідну угоду."

تو پیدا نشدی و من از دست دادن یک معامله میترسیدم.

لم أتمكن من العثور عليك، وكنت خائفًا من فقدان صفقة."

"Bạn không có ở đó, và tôi sợ mất một món hời."

Seni bulamadım ve bir fırsatı kaybetmekten korktum.

Nie mogłem cię znaleźć, a obawiałem się, że stracę okazję.

"Amontillado!"

آمانتیلادو

Amontillado

Амонтильядо

أمونتيلا

Amontillado

“阿蒙蒂亚多!”

Amontillado

Amontillado

amontillado

"¡Amontillado!"

"Amontillado!"

"Амонтильядо!"

"آمانتیلا!"

"أمانتيجادو!"

"Amontillado!"

"Amontillado!"

"Amontillado!"

"I have my doubts."

من|دارم|من|شک و تردیدها

tôi|có|những|nghi ngờ

Я|маю|мої|сумніви

أنا|لدي|شكوكي|الشكوك

ja|mam|moje|wątpliwości

|||疑虑

ben|sahipim|benim|şüpheler

Ich|habe|meine|Zweifel

yo|tengo|mis|dudas

"Tengo mis dudas."

"Ich habe meine Zweifel."

"У мене є сумніви."

"من شک دارم."

"لدي شكوكي."

"Tôi có những nghi ngờ."

"Şüphelerim var."

"Mam swoje wątpliwości."

"Amontillado!"

آمانتیلادو

Amontillado

Амонтильядо

أمونتيلادو

Amontillado

Amontillado

Amontillado

amontillado

"¡Amontillado!"

"Amontillado!"

"Амонтільядо!"

"آمونتیادو!"

"أمونتيادو!"

"Amontillado!"

"Amontillado!"

"Amontillado!"

"And I must satisfy them."

و|من|باید|راضی کنم|آنها

và|tôi|phải|làm thỏa mãn|chúng

І|я|мушу|задовольнити|їх

و|أنا|يجب|أُرضي|هم

i|ja|muszę|zaspokoić|je

|||满足|

ve|ben|zorundayım|tatmin etmek|onları

Und|ich|muss|zufriedenstellen|sie

y|yo|debo|satisfacer|a ellos

"Y debo satisfacerlas."

"Und ich muss sie befriedigen."

"І я повинен їх задовольнити."

"و من باید آنها را راضی کنم."

"ويجب أن أُرضيها."

"Và tôi phải làm cho chúng hài lòng."

"Ve onları tatmin etmeliyim."

"I muszę je zaspokoić."

"Amontillado!"

آمانتیلادو

Amontillado

Амонтильядо

أمونتيلادو

Amontillado

“阿蒙蒂亚多!”

Amontillado

Amontillado

amontillado

"¡Amontillado!"

"Amontillado!"

"Амонтільядо!"

"آمونتیادو!"

"أمونتيادو!"

"Amontillado!"

"Amontillado!"

"Amontillado!"

"As you are engaged, I am on my way to Luchesi.

چون|تو|هستی|نامزد|من|هستم|در|من|راه|به|لوچزی

khi|bạn|đang|đính hôn|tôi|đang|trên|đường|đi|đến|Luchesi

Оскільки|ти|є|заручений|я|є|в|моєму|шляху|до|Лучезі

كما|أنت|تكون|مخطوب|أنا|أكون|في|طريقي|طريق|إلى|لوكيسي

ponieważ|ty|jesteś|zaręczony|ja|jestem|w|mojej|drodze|do|Luchesiego

|||忙碌|||||||卢凯西

-dığı için|sen|-sin|nişanlı|ben|-ım|-da|benim|yolum|-e|Luchesi

Da|du|bist|verlobt|ich|bin|auf|meinen|Weg|zu|Luchesi

como|tú|estás|comprometido|yo|estoy|en|mi|camino|hacia|Luchesi

「既然你訂婚了,我就在去盧切西的路上。

"Como estás comprometido, voy en camino a Luchesi.

"Da Sie beschäftigt sind, bin ich auf dem Weg zu Luchesi.

"Оскільки ви зайняті, я на шляху до Лучезі.

"همانطور که مشغول هستید، من در راه لوشسی هستم.

"بينما أنت مشغول، أنا في طريقي إلى لوكيسي.

"Khi bạn đang bận, tôi đang trên đường đến Luchesi.

"Nişanlı olduğun için, ben Luchesi'ye doğru yoldayım.

"Skoro jesteś zajęty, zmierzam do Luchesiego.

If any one has a critical turn, it is he.

اگر|هر|کسی|دارد|یک|انتقادی|چرخش|آن|است|او

nếu|bất kỳ|ai|có|một|phê phán|xu hướng|nó|là|anh ta

Якщо|будь-хто|один|має|критичний||поворот|це|є|він

إذا|أي|شخص|لديه|اتجاه|نقدي|ميل|هو|يكون|هو

jeśli|ktokolwiek|jeden|ma|krytyczny|krytyczny|zwrot|to|jest|on

eğer|herhangi biri|kişi|-e sahip|bir|eleştirel|yönelim|o|-dir|o

Wenn|irgendjemand|einer|hat|einen|kritischen|Wendepunkt|es|ist|er

si|alguno|uno|tiene|un|crítico|giro|eso|es|él

如果說誰有關鍵轉折的話,那就是他了。

Si alguien tiene un giro crítico, es él.

Wenn jemand einen kritischen Blick hat, dann ist es er.

Якщо хтось має критичний погляд, то це він.

اگر کسی انتقادی باشد، اوست.

إذا كان هناك من لديه نظرة نقدية، فهو هو.

Nếu có ai đó có tính cách phê phán, thì đó chính là anh ta.

Eğer birinin eleştirel bir yönü varsa, o da odur.

Jeśli ktoś ma krytyczne podejście, to on.

He will tell me."

او|خواهد|گفتن|به من

anh ta|sẽ|nói|với tôi

Він|(допоміжне дієслово)|скаже|мені

هو|سوف|يخبر|ني

on|czas przyszły|powie|mi

o|-ecek|söylemek|bana

Er|wird|erzählen|mir

él|(verbo auxiliar futuro)|dirá|a mí

Él me lo dirá."

Er wird es mir sagen."

Він мені скаже."

او به من خواهد گفت."

سوف يخبرني."

Anh ta sẽ nói cho tôi biết."

Bana söyleyecek."

On mi powie."

"Luchesi cannot tell Amontillado from Sherry."

لوشسی|نمی تواند|تشخیص دهد|آمونتیادو|از|شری

Luchesi|không thể|phân biệt|Amontillado|từ|Sherry

Лучезі|не може|відрізнити|Амонтильядо|від|Шеррі

Luchesi|||||

لوكيسي|لا يستطيع|يخبر|أمونتيادو|من|شيري

Luchesi|nie może|odróżnić|Amontillado|od|Sherry

|不能||雪利酒||雪利酒

Luchesi|-amaz|söylemek|Amontillado|-den|Sherry

Luchesi|kann|unterscheiden|Amontillado|von|Sherry

luchesi|no puede|distinguir|amontillado|de|jerez

«Лучези не может отличить Амонтильядо от Шерри».

“盧切西無法區分阿蒙蒂拉多和雪利酒。”

"Luchesi no puede distinguir Amontillado de Jerez."

"Luchesi kann Amontillado nicht von Sherry unterscheiden."

"Лучезі не може відрізнити Амонтильядо від Шеррі."

"لوشسی نمیتواند آمنتیدو را از شری تشخیص دهد."

"لوكيسي لا يستطيع تمييز الأمونتيادو عن الشيري."

"Luchesi không thể phân biệt Amontillado với Sherry."

"Luchesi, Amontillado'yu Sherry'den ayırt edemez."

"Luchesi nie potrafi odróżnić Amontillado od Sherry."

"And yet some fools will have it that his taste is a match for your own."

و|با این حال|برخی|احمق ها|خواهند|داشته باشند|آن|که|او|سلیقه|است|یک|برابر|برای|شما|خود

và|nhưng|một số|kẻ ngu|sẽ|có|điều đó|rằng|của anh ấy|gu|thì|một|sự tương xứng|với|của bạn|riêng

І|все ж|деякі|дурні|будуть|стверджувати|це|що|його|смак|є|таким|рівнем|для|твого|власного

و|لكن|بعض|الحمقى|سوف|لديهم|ذلك|أن|ذوقه|ذوق|هو|مطابقة|مطابقة|ل|ذوقك|الخاص

i|jednak|niektórzy|głupcy|czasownik posiłkowy|będą mieli|to|że|jego|smak|jest|dopasowaniem|dopasowaniem|do|twojego|własnego

|||傻瓜||||||品味||||||

ve|yine de|bazı|aptallar|-ecekler|sahip|onu|ki|onun|tadı|-dir|bir|eşleşme|için|senin|kendin

Und|doch|einige|Narren|werden|haben|es|dass|sein|Geschmack|ist|ein|ebenbürtig|für|dein|eigener

y|sin embargo|algunos|tontos|(verbo auxiliar futuro)|tendrán|eso|que|su|gusto|es|un|igual|para|tu|propio

«И все же некоторые дураки будут думать, что его вкус совпадает с вашим».

“然而,有些傻瓜會認為他的品味與你的品味相符。”

"Y sin embargo, algunos tontos dirán que su gusto es igual al tuyo."

"Und doch werden einige Narren behaupten, dass sein Geschmack mit deinem eigenen übereinstimmt."

"І все ж деякі дурні вважають, що його смак зрівняється з твоїм."

"و با این حال برخی احمقها بر این باورند که سلیقهاش با سلیقه شما برابر است."

"ومع ذلك، سيقول بعض الحمقى إن ذوقه يتناسب مع ذوقك."

"Và vẫn có một số kẻ ngốc cho rằng gu của anh ta tương xứng với của bạn."

"Ve yine bazı aptallar onun zevkinin seninkiyle eşleştiğini iddia edecekler."

"A jednak niektórzy głupcy twierdzą, że jego gust jest równy twojemu."

"Come, let us go."

بیا|بگذار|ما|برویم

đến|hãy|chúng ta|đi

Іди|давай|нам|підемо

تعال|دع|لنا|نذهب

chodź|pozwól|nam|iść

gel|izin ver|bize|gidelim

Komm|lass|uns|gehen

ven|dejemos|nosotros|vamos

«Пойдем, пойдем».

"Vamos, vayamos."

"Komm, lass uns gehen."

"Іди, підемо."

"بیا، برویم."

"هيا، دعنا نذهب."

"Đi nào, chúng ta hãy đi."

"Hadi, gidelim."

"Chodź, idźmy."

"Whither?"

به کجا؟

đâu

Куди

إلى أين

dokąd

何去何从?

nereye

Wohin

adónde

"Куда?"

“去哪兒?”

"¿A dónde?"

"Wohin?"

"Куди?"

"به کجا؟"

"إلى أين؟"

"Đi đâu?"

"Nereye?"

"Dokąd?"

"To your vaults."

به|شما|خزانه ها

đến|của bạn|hầm

До|ваших|сховищ

||vaults

إلى|خزائنك|خزائن

do|twoich|skarbców

||金库

-e|senin|mahzenler

Zu|deinen|Tresoren

a|tus|bóvedas

«В свои хранилища».

“去你的金庫。”

"A tus bóvedas."

"In deine Gewölbe."

"До твоїх скарбниць."

"به خزانههای تو."

"إلى خزائنك."

"Đến hầm của bạn."

"Senin mahzenlerine."

"Do twoich skarbców."

"My friend, no ; I will not impose upon your good nature.

دوست من|دوست|نه|من|خواهم|نه|تحمیل کنم|بر|تو|خوب|طبیعت

bạn|tôi|không|tôi|sẽ|không|áp đặt|lên|của bạn|tốt|bản chất

Мій|друг|ні|я|буду|не|нав'язуватися|на|твою|добру|натуру

||||||impose||||

صديقي|صديق|لا|أنا|سوف|لا|أفرض|على|طبيعتك|جيدة|طبيعة

||||||impor||||

mój|przyjaciel|nie|ja|czas przyszły|nie|narzucać|na|twoją|dobrą|naturę

||||||打扰|利用|||好意

benim|arkadaşım|hayır|ben|-acak|değil|zorlamak|üzerine|senin|iyi|doğa

Mein|Freund|nein|ich|werde|nicht|auferlegen|auf|dein|gute|Natur

mi|amigo|no|yo|(verbo auxiliar futuro)|no|imponer|sobre|tu|buena|naturaleza

-- Друг мой, нет, я не буду навязывать вам вашу добрую натуру.

「我的朋友,不;我不會強加於你的善良本性。

"Amigo mío, no; no voy a abusar de tu buena naturaleza."

"Mein Freund, nein; ich möchte deine Gutmütigkeit nicht überstrapazieren."

"Мій друже, ні; я не буду нав'язувати тобі свою добру натуру.

"دوست من، نه؛ من بر طبیعت خوب شما تحمیل نخواهم کرد.

"صديقي، لا؛ لن أفرض عليك طبيعتك الطيبة.

"Bạn tôi, không; tôi sẽ không áp đặt lên bản chất tốt đẹp của bạn.

"Arkadaşım, hayır; senin iyi doğana yüklenmeyeceğim.

"Mój przyjacielu, nie; nie będę narzucał się twojej dobrej naturze.

I perceive you have an engagement.

من|درک میکنم|تو|داری|یک|نامزدی

tôi|nhận thấy|bạn|có|một|cuộc hẹn

Я|помічаю|ти|маєш|одне|заручини

أنا|أدرك|أنت|لديك|التزام|التزام

ja|dostrzegam|ciebie|masz|jakieś|zobowiązanie

|察觉到||||约会

ben|algılıyorum|seni|var|bir|randevu

Ich|nehme wahr|du|hast|ein|Engagement

yo|percibo|tú|tienes|un|compromiso

Я так понимаю, у вас помолвка.

我發現你已經訂婚了。

Percibo que tienes un compromiso.

Ich nehme wahr, dass Sie eine Verabredung haben.

Я бачу, що у тебе є зобов'язання.

من متوجه هستم که شما یک قرار دارید.

أرى أن لديك ارتباطاً.

Tôi nhận thấy bạn có một cuộc hẹn.

Bir randevun olduğunu anlıyorum.

Widzę, że masz zobowiązanie.

Luchesi --"

لوچسی

Luchesi

Лучезі

لوكيسي

Luchesi

Luchesi

Luchesi

luchesi

Лучези --"

Luchesi --"

Luchesi --

Лучесі --"

لوچسی --"

لوتشيزي --"

Luchesi --"

Luchesi --"

Luchesi --"

"I have no engagement.

من|دارم|هیچ|نامزدی

tôi|có|không|cuộc hẹn

Я|маю|немає|заручин

أنا|لدي|لا|التزام

ja|mam|żadnego|zobowiązania

|||约会

ben|var|hiç|randevu

Ich|habe|kein|Engagement

yo|tengo|ningún|compromiso

"У меня нет помолвки.

"No tengo compromiso.

"Ich habe keine Verabredung.

"У мене немає зобов'язань.

"من هیچ قراری ندارم.

"ليس لدي أي ارتباط.

"Tôi không có cuộc hẹn nào.

"Hiçbir randevum yok.

"Nie mam żadnego zobowiązania.

Come."

بیا

đến

Прийди

تعال

przyjdź

gel

Komm

ven

Прийти."

Ven."

Kommen Sie."

"Іди."

بیا.

"تعال."

"Đến đây."

Gel.

"Chodź."

"My friend, no.

دوست من|دوست|نه

bạn|bạn|không

Мій|друг|ні

صديقي|صديق|لا

mój|przyjaciel|nie

benim|arkadaşım|hayır

Mein|Freund|nein

mi|amigo|no

"Мой друг, нет.

"Amigo mío, no.

"Mein Freund, nein.

"Мій друже, ні.

دوست من، نه.

"صديقي، لا.

"Bạn tôi, không."},{

"Arkadaşım, hayır.

"Mój przyjacielu, nie.

It is not the engagement, but the severe cold with which I perceive you are afflicted.

آن|است|نه|آن|نامزدی|بلکه|آن|شدید|سرما|با|که|من|درک می کنم|تو|هستی|مبتلا

nó|thì|không|cái|đính hôn|nhưng|cái|nghiêm trọng|lạnh|với|cái mà|tôi|nhận thấy|bạn|thì|bị ảnh hưởng

Це|є|не|те|заручини|але|те|сильний|холод|з|яким|я|сприймаю|ти|є|страждаєш

ذلك|يكون|ليس|ال|خطوبة|لكن|ال|شديد|برد|مع|الذي|أنا|أدرك|أنت|تكون|مصاب

to|jest|nie|to|zaręczyny|ale|zimno|surowe|zimno|z|którym|ja|dostrzegam|ciebie|jesteś|dotknięty

||||订婚|||||伴随|||感受到|||折磨

bu|-dir|değil|bu|nişan|ama|bu|şiddetli|soğuk|ile|ki|ben|algılıyorum|seni|-sin|etkilenmiş

Es|ist|nicht|das|Engagement|sondern|die|strenge|Kälte|mit|der|ich|wahrnehme|du|bist|betroffen

(eso)|es|no|el|compromiso|sino|el|severo|frío|con|la cual|yo|percibo|tú|estás|afligido

Дело не в помолвке, а в сильной простуде, которой, как я вижу, вы страдаете.

我覺得你受苦的不是訂婚,而是嚴寒。

No es el compromiso, sino el frío severo con el que percibo que estás afligido.

Es ist nicht das Engagement, sondern die schwere Kälte, mit der ich wahrnehme, dass Sie betroffen sind.

Це не заручини, а сувора холоднеча, якою я бачу, що ти страждаєш.

این نه به خاطر نامزدی، بلکه به خاطر سرما شدید است که من متوجه میشوم تو به آن مبتلا هستی.

ليس الأمر متعلقًا بالخطوبة، بل بالبرد الشديد الذي أشعر أنك تعاني منه.

Bu nişan değil, ama senin acı çektiğin şiddetli soğuk.

To nie zaręczyny, ale surowy zimno, z którym dostrzegam, że jesteś dotknięty.

The vaults are insufferably damp.

(حرف تعریف مشخصه)|طاق ها|هستند|به طرز غیرقابل تحملی|مرطوب

những|hầm|thì|không thể chịu đựng|ẩm ướt

Склепи|склепи|є|нестерпно|вологими

|||insufferably|

ال|قبو|تكون|لا يطاق|رطب

te|sklepienia|są|nieznośnie|wilgotne

|拱顶房间||难以忍受地|潮湿

bu|mahzenler|-dir|dayanılmaz şekilde|nemli

Die|Gewölbe|sind|unerträglich|feucht

las|bóvedas|están|insoportablemente|húmedas

拱頂潮濕得令人難以忍受。

Las bóvedas son insoportablemente húmedas.

Die Gewölbe sind unerträglich feucht.

Склепи нестерпно вологі.

زیرزمینها به طرز غیرقابل تحملی مرطوب هستند.

الأقبية رطبة بشكل لا يطاق.

Kemerler dayanılmaz derecede nemli.

Krypta jest nieznośnie wilgotna.

They are encrusted with nitre."

آنها|هستند|پوشیده|با|نیتر

họ|thì|được bao phủ|với|muối nitrat

Вони|є|вкрите|нітратом|нітратом

||||saltpeter

هم|يكونون|مغطاة|بـ|نترات

oni|są|pokryci|azotem|azot

||覆盖着||硝石

onlar|-dir|kaplanmış|ile|nitre

Sie|sind|eingekrustet|mit|Salpeter

ellos|están|incrustados|con|nitro

它們上面覆蓋著硝石。”

Están incrustadas con nitro."

Sie sind mit Salpeter überzogen."

"Вони вкрити нітратом."

آنها با نیترات پوشیده شدهاند.

إنها مغطاة بالنترات.

Chúng được bao phủ bởi muối nitre.

"Nitratla kaplanmışlar."

Są pokryte saletrą."

"Let us go, nevertheless.

بگذارید|ما|برویم|با این حال

hãy|chúng ta|đi|tuy nhiên

Давай|нам|підемо|все ж

دع|لنا|نذهب|مع ذلك

niech|nas|idziemy|jednak

|||尽管如此

bırak|bizi|gidelim|yine de

Lass|uns|gehen|trotzdem

(verbo auxiliar)|nosotros|vamos|sin embargo

「儘管如此,我們還是走吧。

"Vayamos, sin embargo.

"Lass uns trotzdem gehen.

"Проте, давайте підемо.

با این حال، بیایید برویم.

دعنا نذهب، على أي حال.

"Chúng ta hãy đi, dù sao đi nữa.

"Yine de gidelim.

"Chodźmy, mimo wszystko.

The cold is merely nothing.

(مفرد)|سرما|است|فقط|هیچ چیز

cái|lạnh|thì|chỉ|không có gì

Холод|холод|є|лише|нічим

البرد|البرد|يكون|فقط|لا شيء

ten|zimno|jest|jedynie|nic

|||仅仅|

soğuk|soğuk|-dir|sadece|hiçbir şey

Die|Kälte|ist|nur|nichts

el|frío|es|meramente|nada

El frío no es nada.

Die Kälte ist nur nichts.

Холод - це всього лише нічого.

سرما فقط هیچ چیز است.

البرودة ليست شيئًا.

Cái lạnh chỉ là một điều không đáng.

Soğuk sadece bir şey değil.

Zimno to tylko nic.

Amontillado!

آمانتیلادو

Amontillado

Амонтильядо

أمونتيلادو

Amontillado

阿蒙蒂亚多

Amontillado

Amontillado

amontillado

¡Amontillado!

Amontillado!

Амонтільядо!

آمونتیلادو!

أمونتيادو!

Amontillado!

Amontillado!

Amontillado!

You have been imposed upon.

ty|masz|zostałeś|narzucony|na

sen|sahip oldun|olmuş|dayatılmış|üzerine

Te han impuesto.

Du bist hereingelegt worden.

Вам нав'язали.

بر شما تحمیل شده است.

لقد تم فرضك.

Bạn đã bị áp đặt.

Sana baskı yapıldı.

Zostałeś nałożony.

And as for Luchesi, he cannot distinguish Sherry from Amontillado."

a|jak|dla|Luchesiego|on|nie może|odróżnić|Sherry|od|Amontillado

ve|olarak|için|Luchesi|o|yapamaz|ayırt etmek|Sherry|den|Amontillado

Y en cuanto a Luchesi, no puede distinguir el Jerez del Amontillado."

Und was Luchesi betrifft, er kann Sherry nicht von Amontillado unterscheiden."

А що стосується Лучезі, він не може відрізнити Шеррі від Амонтильядо."

و اما در مورد لوچسی، او نمیتواند شری را از آمونتیلادو تشخیص دهد.

أما بالنسبة لوتشيسي، فلا يمكنه تمييز الشيري عن الأمانتيلا.

Còn về Luchesi, anh ta không thể phân biệt Sherry với Amontillado."

Ve Luchesi'ye gelince, o Sherry'yi Amontillado'dan ayırt edemez.

A jeśli chodzi o Luchesiego, nie potrafi odróżnić Sherry od Amontillado."

Thus speaking, Fortunato possessed himself of my arm.

więc|mówiąc|Fortunato|opanował|siebie|na|mój|ramię

böyle|konuşarak|Fortunato|sahip oldu|kendine|üzerine|benim|kolum

Así hablando, Fortunato se apoderó de mi brazo.

So sprach Fortunato und ergriff meinen Arm.

Так говоривши, Фортунато схопив мене за руку.

بدین ترتیب، فورتوناتو دست مرا گرفت.

وبهذا الكلام، استحوذ فورتونات على ذراعي.

Nói như vậy, Fortunato đã nắm lấy cánh tay tôi.

Böyle konuşarak, Fortunato koluma girdi.

Mówiąc to, Fortunato objął mnie ramieniem.

Putting on a mask of black silk, and drawing a roquelaire closely about my person, I suffered him to hurry me to my palazzo.

zakładając|na|maskę||z|czarnego|jedwabiu|i|zaciągając|pelerynę|roquelaire|ściśle|wokół|mojej|osoby|ja|pozwoliłem|mu|aby|pospieszył|mnie|do|mojego|pałacu

takarak|üzerine|bir|maske|den|siyah|ipek|ve|çekerek|bir|roquelaire|sıkı|etrafında|benim|bedenim|ben|izin verdim|ona|-e|acele etmek|beni|-e|benim|sarayım

我戴上黑色絲綢面具,在身上貼上一條羅克萊萊爾紗,讓他催促我趕往我的宮殿。

Poniéndome una máscara de seda negra y ajustando un roquelaire alrededor de mi persona, le permití que me apresurara a mi palazzo.

Indem ich eine Maske aus schwarzer Seide aufsetzte und einen Roquelaire eng um meinen Körper zog, ließ ich ihn mich zu meinem Palast drängen.

Надівши маску з чорного шовку і щільно закутавшись у рокаєр, я дозволив йому потягти мене до мого палаццо.

با گذاشتن یک ماسک ابریشمی سیاه و کشیدن یک روکلا به دور بدنم، اجازه دادم که او مرا به پالازویم ببرد.

وضع قناعًا من الحرير الأسود، وسحب روجلاير بإحكام حول جسدي، وسمحت له بأن يسرع بي إلى قصر.

Đeo một chiếc mặt nạ bằng lụa đen, và kéo chặt một chiếc roquelaire quanh người, tôi để anh ta vội vã đưa tôi đến palazzo của tôi.

Siyah ipek bir maske takarak ve roquelaire'ı vücuduma sıkıca sararak, beni palazzo'ma acele ettirmesine izin verdim.

Zakładając maskę z czarnego jedwabiu i ściśle otulając się roquelaire, pozwoliłem mu poprowadzić mnie do mojego pałacu.

There were no attendants at home; they had absconded to make merry in honor of the time.

آنجا|بودند|هیچ|مهمانان|در|خانه|آنها|داشتند|فرار کردند|برای|جشن گرفتن|شاد|در|احترام|به|آن|زمان

có|thì|không|người phục vụ|ở|nhà|họ|đã|bỏ trốn|để|làm|vui vẻ|để|vinh danh|về|thời gian|

Там|були|немає|присутні|вдома|вдома|вони|мали|втекли|щоб|веселитися|весело|на|честь|часу|часу|часу

||||||||escaped||||||||

هناك|كان|لا|خدم|في|المنزل|هم|كانوا|هربوا|ل|جعل|مرحين|في|تكريم|ل|الوقت|

tam|byli|żadni|służący|w|domu|oni|mieli|uciekli|aby|robić|wesoło|na|cześć|dla|tego|czasu

|||仆人|||||逃跑了|||欢庆||庆祝|||

orada|vardı|hiç|hizmetkarlar|-de|evde|onlar|-dılar|kaçmışlardı|-mek için|yapmak|eğlenmek|-de|onur|-ın|bu|zaman

Es|waren|keine|Anwesenden|zu|Hause|sie|hatten|geflohen|um|feiern|fröhlich|zu|Ehren|von|der|Zeit

allí|estaban|ningunos|asistentes|en|casa|ellos|habían|huido|para|hacer|fiesta|en|honor|de|el|tiempo

家裡沒有服務生;他們潛逃是為了慶祝這個時刻。

No había asistentes en casa; se habían escapado para festejar en honor al momento.

Es waren keine Anwesenden zu Hause; sie waren verschwunden, um zu feiern, um der Zeit zu gedenken.

Дома не було нікого; вони втекли, щоб повеселитися на честь цього часу.

هیچ کدام از خدمتکاران در خانه نبودند؛ آنها به منظور جشن گرفتن به خاطر این زمان فرار کرده بودند.

لم يكن هناك أي خدم في المنزل؛ لقد هربوا للاحتفال تكريماً لهذه المناسبة.

Không có ai ở nhà; họ đã bỏ trốn để vui vẻ nhân dịp này.

Evde hiç kimse yoktu; eğlenmek için kaçmışlardı.

W domu nie było nikogo; uciekli, aby się bawić na cześć tego czasu.

I had told them that I should not return until the morning, and had given them explicit orders not to stir from the house.

ja|miałem|powiedziałem|im|że|ja|miałbym|nie|wrócić|aż|do|rana|i|miałem|dałem|im|wyraźne|rozkazy|nie|aby|ruszać|z|domu|

tôi|đã|nói|họ|rằng|tôi|sẽ|không|trở về|cho đến khi|buổi|sáng|và|đã|đưa|họ|rõ ràng|lệnh|không|để|động|ra khỏi|ngôi|nhà

ben|-dım|söyledim|onlara|ki|ben|-meliyim|değil|dönmek|-e kadar|sabah||ve|-dım|verdim|onlara|açık|emirler|değil|-mek|kıpırdamak|-den|evden|

我告訴他們早上之前我不能回來,並明確命令他們不要離開房子。

Les había dicho que no regresaría hasta la mañana, y les había dado órdenes explícitas de no moverse de la casa.

Ich hatte ihnen gesagt, dass ich bis zum Morgen nicht zurückkehren würde, und hatte ihnen ausdrücklich befohlen, das Haus nicht zu verlassen.

Я сказав їм, що не повернуся до ранку, і дав їм чіткі накази не виходити з дому.

به آنها گفته بودم که تا صبح برنمیگردم و دستورات صریحی به آنها داده بودم که از خانه خارج نشوند.

كنت قد أخبرتهم أنني لن أعود حتى الصباح، وأعطيتهم أوامر صريحة بعدم مغادرة المنزل.

Tôi đã nói với họ rằng tôi sẽ không trở về cho đến sáng, và đã ra lệnh rõ ràng cho họ không được rời khỏi nhà.

Onlara sabaha kadar dönmeyeceğimi söylemiştim ve evden ayrılmamaları için kesin emirler vermiştim.

Powiedziałem im, że nie wrócę aż do rana, i dałem im wyraźne polecenia, aby nie ruszali się z domu.

These orders were sufficient, I well knew, to insure their immediate disappearance, one and all, as soon as my back was turned.

te|rozkazy|były|wystarczające|ja|dobrze|wiedziałem|aby|zapewnić|ich|natychmiastowe|zniknięcie|jeden|i|wszyscy|gdy|szybko|jak|moje|plecy|było|obrócone

những|lệnh|thì|đủ|tôi|tốt|biết|để|đảm bảo|sự|ngay lập tức|biến mất|một|và|tất cả|khi|sớm|khi|lưng|quay|thì|quay

bu|emirler|-di|yeterli|ben|iyi|biliyordum|-mek için|garanti etmek|onların|hemen|kayboluşları|bir|ve|hepsi|-dığı zaman|yakında|-dığı zaman|benim|sırtım|-di|döndü

我深知这些命令足以确保一到两秒后,当我转过身时,他们立刻会全部消失。

我很清楚,這些命令足以確保我一轉身,他們就會立刻消失。

Sabía bien que estas órdenes eran suficientes para asegurar su inmediata desaparición, uno y todos, tan pronto como me diera la vuelta.

Diese Befehle waren, wie ich wohl wusste, ausreichend, um ihr sofortiges Verschwinden, eines nach dem anderen, zu gewährleisten, sobald ich mich umdrehte.

Цих наказів було достатньо, я добре знав, щоб забезпечити їхнє негайне зникнення, всіх без винятку, щойно я відвернуся.

این دستورات به خوبی میدانستم که کافی است تا ناپدید شدن فوری آنها را تضمین کند، به محض اینکه پشت سرم را برگردانم.

كنت أعلم جيداً أن هذه الأوامر كافية لضمان اختفائهم الفوري، جميعهم، بمجرد أن ألتفت.

Tôi biết rõ rằng những lệnh này đủ để đảm bảo sự biến mất ngay lập tức của họ, từng người một, ngay khi tôi quay lưng.

Bu emirlerin, arkamı döner dönmez hepsinin hemen kaybolmasını sağlamak için yeterli olduğunu iyi biliyordum.

Te polecenia były wystarczające, dobrze wiedziałem, aby zapewnić ich natychmiastowe zniknięcie, jeden i wszyscy, jak tylko odwrócę się plecami.

I took from their sconces two flambeaux, and giving one to Fortunato, bowed him through several suites of rooms to the archway that led into the vaults.

ja|wziąłem|z|ich|kinkietów|dwa|pochodnie|i|dając|jedną|Fortunato||skłoniłem|go|przez|kilka|pomieszczeń|w|pokojach|do|łuku|przejście|które|prowadziło|do|katakumb|katakumb

tôi|lấy|từ|những|giá nến|hai|đuốc|và|đưa|một|cho|Fortunato|cúi chào|anh ấy|qua|vài|phòng|của|phòng|đến|cổng|cổng|mà|dẫn|vào|hầm|hầm

ben|aldım|-den|onların|duvar lambalarından|iki|meşale|ve|vererek|bir|-e|Fortunato'ya|eğdim|ona|-den|birkaç|oda|-in|odalara|-e|kemer|geçit|ki|götüren|-e|mahzenlere|mahzenlere

我从墙上的炬台上拿下两支火炬,把一支递给幸运儿,然后领着他穿过几个套间,来到通往墓穴的拱门处。

我從他們的燭台上取出兩支火炬,把一支交給福爾圖納托,向他鞠躬,穿過幾間房間,來到通往金庫的拱門。

Tomé de sus apliques dos antorchas, y dándole una a Fortunato, lo guié a través de varias suites de habitaciones hasta el arco que conducía a las bóvedas.

Ich nahm zwei Fackeln von ihren Wandleuchtern und gab eine Fortunato, während ich ihn durch mehrere Zimmer zu dem Torbogen führte, der in die Gewölbe führte.

Я взяв з їхніх світильників два факели і, давши один Фортунато, провів його через кілька кімнат до арки, що вела в підвали.

از شمعدانهایشان دو مشعل برداشتم و یکی را به فورتوناتو دادم و او را از چندین اتاق به سمت طاقی که به سردابها میرسید، هدایت کردم.

أخذت من الشمعدانات اثنين من المشاعل، وأعطيت واحدة لفورتونات، وانحنيت به عبر عدة غرف إلى المدخل الذي يؤدي إلى القبو.

Tôi đã lấy từ những giá nến hai ngọn đuốc, và đưa một ngọn cho Fortunato, cúi chào anh ta qua vài dãy phòng đến cổng dẫn vào hầm.

Duvarlardaki iki meşaleyi aldım ve birini Fortunato'ya vererek, onu birkaç oda boyunca kemer kapısına kadar götürdüm.

Wziąłem z ich świeczników dwa pochodnie i dając jedną Fortunato, poprowadziłem go przez kilka pokoi do łuku, który prowadził do katakumb.

I passed down a long and winding staircase, requesting him to be cautious as he followed.

من|پایین رفتم|به سمت پایین|یک|بلند|و|پیچ در پیچ|پله ها|درخواست کردن|او|به|باشد|محتاط|در حالی که|او|دنبال کرد

tôi|đã đi qua|xuống|một|dài|và|quanh co|cầu thang|yêu cầu|anh ấy|để|hãy|cẩn thận|khi|anh ấy|theo sau

Я|спустився|вниз|один|довгий|і|звивистий|сходи|просячи|його|бути||обережним|коли|він|слідував

أنا|نزلت|إلى أسفل||طويل|و|متعرج|درج|أطلب|له|أن|يكون|حذراً|عندما|هو|تبع

ja|przeszedłem|w dół|jeden|długi|i|kręty|schody|prosząc|go|aby|był|ostrożny|gdy|on|podążał

||||||||请求他||||小心谨慎|||跟随

ben|geçtim|aşağı|bir|uzun|ve|dolambaçlı|merdiven|isteyerek|ona|-mesi|olmasını|dikkatli|-dığı için|o|takip etti

Ich|ging|hinunter|eine|lange|und|gewundene|Treppe|bat|ihn|zu|sein|vorsichtig|während|er|folgte

yo|bajé|por|una|larga|y|sinuosa|escalera|pidiéndole|a él|que|esté|cuidadoso|mientras|él|seguía

我走过一条又长又弯的楼梯,提醒他在后面时要小心。

我走下一段又長又曲折的樓梯,吩咐他後面要小心。

Bajé por una larga y sinuosa escalera, pidiéndole que tuviera cuidado mientras me seguía.

Ich ging eine lange und gewundene Treppe hinunter und bat ihn, vorsichtig zu sein, während er mir folgte.

Я спустився довгими і звивистими сходами, просячи його бути обережним, коли він слідував за мною.

من از یک پلهبرقی طولانی و پیچدرپیچ پایین رفتم و از او خواستم که در حین پیروی احتیاط کند.

نزلت عبر درج طويل ومتعرج، طالبة منه أن يكون حذراً أثناء متابعته.

Tôi đi xuống một cầu thang dài và quanh co, yêu cầu anh ấy cẩn thận khi theo sau.

Uzun ve dolambaçlı bir merdivenden indim, onun dikkatli olmasını isteyerek arkamdan gelmesini söyledim.

Zszedłem długimi i krętymi schodami, prosząc go, aby był ostrożny, gdy mnie naśladował.

We came at length to the foot of the descent, and stood together on the damp ground of the catacombs of the Montresors.

ما|رسیدیم|در|نهایت|به|آن|پای|از|آن|سراشیبی|و|ایستادیم|با هم|بر|آن|مرطوب|زمین|از|آن|کاتاکومب|از|آن|مانترسورها

chúng tôi|đã đến|vào|cuối cùng|đến|cái|chân|của|cái|dốc|và|đã đứng|cùng nhau|trên|cái|ẩm|mặt đất|của|cái|hầm mộ|của|gia đình|Montresors

Ми|прийшли|на|кінець|до||підніжжя|спуску||спуску|і|стояли|разом|на||вологому|ґрунті|||катакомбах|||Монтресорів

نحن|وصلنا|في|النهاية|إلى||قاعدة|من||انحدار|و|وقفنا|معاً|على||رطب|أرض|من||سراديب|من||مونتريزور

my|przyszliśmy|na|w końcu|do|u|stóp|z|tego|zejścia|i|stanęliśmy|razem|na|tej|wilgotnej|ziemi|w|katakumbach||rodu|Montresors|

||||||脚下|||下坡路||站立||||潮湿的||||地下墓穴|||蒙特雷索家族

biz|geldik|-de|sonunda|-e|-e|ayak|-in|-in|iniş|ve|durduk|birlikte|-de|-in|nemli|zemin|-in|-in|katakomb|-in|-in|Montresor'lar

Wir|kamen|an|endlich|zu|dem|Fuß|des|der|Abstieg|und|standen|zusammen|auf|dem|feuchten|Boden|der||Katakomben|der||Montresors

nosotros|llegamos|a|largo|al|el|pie|de|la|bajada|y|nos paramos|juntos|en|el|húmedo|suelo|de|las|catacumbas|de|los|Montresors

我們終於來到了山坡腳下,一起站在蒙特雷索地下墓穴潮濕的地面上。

Finalmente llegamos al pie del descenso y nos quedamos juntos en el suelo húmedo de las catacumbas de los Montresor.

Wir kamen schließlich zu den Füßen des Abstiegs und standen zusammen auf dem feuchten Boden der Katakomben der Montresors.

Нарешті ми дійшли до підніжжя спуску і стояли разом на вологій землі катакомб Монтресорів.

ما در نهایت به پای شیب رسیدیم و در کنار هم بر روی زمین مرطوب کاتاکومبهای مونترسور ایستادیم.

وصلنا في النهاية إلى أسفل المنحدر، ووقفنا معاً على الأرض الرطبة لسراديب الموتى لعائلة مونتريسو.

Cuối cùng chúng tôi đến chân dốc, và đứng cùng nhau trên mặt đất ẩm ướt của những hầm mộ của gia đình Montresor.

Sonunda inişin dibine geldik ve Montresorların katakombalarının nemli zemininde birlikte durduk.

W końcu dotarliśmy do stóp zejścia i staliśmy razem na wilgotnej ziemi katakumb Montresorów.

The gait of my friend was unsteady, and the bells upon his cap jingled as he strode.