33. Retreat of the Ten Thousand

"A march in the ranks hard-pressed and the road unknown." —W. WHITMAN.

Socrates was dead, and the brilliant period, which had made Athens the mistress of Greece, was dead too. Pericles had foreseen truly that sooner or later there must be war between Athens and Sparta. It was well for him that he died before the result of that war was known; for the fall of his beautiful city, which took place during the lifetime of Socrates, would have broken his heart. After a long war the Spartans took formal possession of Athens; but to accomplish this, they had called in the help of the Persians.

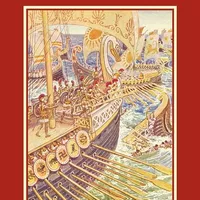

And so it came to pass, when the Persians wanted help, they called in the help of the Spartan Greeks. It is a wonderful story, how ten thousand Greeks marched into the very heart of the Persian empire, and a yet more wonderful one of their retreat.

The expedition started two years before the death of Socrates. It was led by Cyrus, the younger brother of the reigning King of Persia, who wished to make himself king instead. But the true object of the expedition was kept secret from the Greek soldiers.

Marching inland through Asia Minor, they skirted the north of Phœnicia and marched on till they reached the river Euphrates. Here it was impossible to keep from the Greeks, the secret, that they were indeed marching against the King of Persia. To the complaining army, which had been so deceived, Cyrus was full of promises. Each soldier should receive a year's pay, and "to each of you Greeks, moreover," added Cyrus, "I shall present a wreath of gold." This speech impressed the Greeks favourably, and they agreed to go on. They now plunged into the desert, "smooth as a sea, treeless," but alive with all kinds of beasts strange to the Greek eyes—wild asses, ostriches, and antelopes. For thirteen days they tramped through the desert, until they reached the edge of the land of Babylon.

And now they learned that the king's host was advancing. It was not long before the two armies were engaged in battle. But though the King of Persia was well prepared, and had a strong force of Egyptians to help him, the Greeks won the victory. The Persians were flying before them, when suddenly Cyrus caught sight of his brother,—the brother whom he hated with his whole soul. He galloped forward, hoping to slay him with his own hand. He got near enough to throw his javelin and wound him, but in the scuffle that ensued Cyrus was slain.

The Greeks were now in the heart of Persia, girt about by foes on every side—their leader dead, their cause destroyed. Their one great desire was to get home. But they had no food, and they did not know the way. The king now pretended he would send a guide who would take them safely back to their own country; but treachery was at work, and the Greeks were deserted when they were yet eight months' march, by the shortest way from home. Rivers and desert land lay before them; Persian troops were waiting to fall on them. They were in despair. Few ate any supper that night; every man lay down to rest, but not to sleep, for they were heavy with sorrow, and longing for those they might never see again.

Amid the ranks was a young Athenian called Xenophon. He had been a pupil of Socrates. That night he had a dream which made him spring up at dawn.

"Why am I lying here?" he cried to himself. "At daybreak the enemy will be upon us and we shall be killed." He called the officers together; he urged immediate action. His speech put new life into the despairing men; they swore to obey him, and so began one of the most wonderful marches the world has ever seen. They went on till they came to the mountains, where dwelt some wild tribes, who stood on steep heights shooting arrows and throwing down stones at them. After much suffering and loss of life, they reached Armenia. It was December, and their way home lay through wintry snows and ice. On and on plodded the Ten Thousand; cold and hunger was their lot, but home lay before them, and encouraged by their young leader Xenophon, they would reach Greece yet.

Suddenly, one day, a great cry arose from those in front. Xenophon, who was behind with the rear, galloped up quickly, fearing an enemy. As fresh men galloped to the front, the cry increased.

"The sea! the sea!" cried the Greeks, as they reached the summit of a hill and saw in the distance the blue waters. The sight of the sea was to the weary men, as the sight of home. Their troubles would soon be over now, and they wept on each other's necks for very joy. It was only the Black Sea, and they had many long miles yet to march.

Now that the danger of attack was over, the army began to loose its strength of union, and Xenophon had all he could do to keep it together.

Notwithstanding Xenophon's entreaties, the Ten Thousand, now reduced in numbers, fell away from the brave beginnings. They plundered the country through which they passed, and at last Xenophon handed them over to a Spartan general to take charge of them.

Then Xenophon returned to Athens, and settling in a quiet country place near Olympia, he wrote the account of the Retreat of the Ten Thousand, and it is due to his industry and talent, that we know the famous story of their wonderful march.