CHAPTER 15, part 1

CHAPTER 15

Woven and Then Spun

'Come in, Irene,' said the silvery voice of her grandmother. The princess opened the door and peeped in. But the room was quite dark and there was no sound of the spinning-wheel. She grew frightened once more, thinking that, although the room was there, the old lady might be a dream after all. Every little girl knows how dreadful it si to find a room empty where she thought somebody was; but Irene had to fancy for a moment that the person she came to find was nowhere at all.

She remembered, however, that at night she spun only in the moonlight, and concluded that must be why there was no sweet, bee-like humming: the old lady might be somewhere in the darkness. Before she had time to think another thought, she heard her voice again, saying as before:

'Come in, Irene. ' From the sound, she understood at once that she was not in the room beside her. Perhaps she was in her bedroom. She turned across the passage, feeling her way to the other door. When her hand fell on the lock, again the old lady spoke:

'Shut the other door behind you, Irene. I always close the door of my workroom when I go to my chamber.' Irene wondered to hear her voice so plainly through the door: having shut the other, she opened it and went in. Oh, what a lovely haven to reach from the darkness and fear through which she had come! The soft light made her feel as if she were going into the heart of the milkiest pearl; while the blue walls and their silver stars for a moment perplexed her with the fancy that they were in reality the sky which she had left outside a minute ago covered with rainclouds.

'I've lighted a fire for you, Irene: you're cold and wet,' said her grandmother. Then Irene looked again, and saw that what she had taken for a huge bouquet of red roses on a low stand against the wall was in fact a fire which burned in the shapes of the loveliest and reddest roses, glowing gorgeously between the heads and wings of two cherubs of shining silver. And when she came nearer, she found that the smell of roses with which the room was filled came from the fire-roses on the hearth.

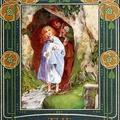

Her grandmother was dressed in the loveliest pale blue velvet, over which her hair, no longer white, but of a rich golden colour, streamed like a cataract, here falling in dull gathered heaps, there rushing away in smooth shining falls. And ever as she looked, the hair seemed pouring down from her head and vanishing in a golden mist ere it reached the floor. It flowed from under the edge of a circle of shining silver, set with alternated pearls and opals. On her dress was no ornament whatever, neither was there a ring on her hand, or a necklace or carcanet about her neck. But her slippers glimmered with the light of the Milky Way, for they were covered with seed-pearls and opals in one mass. Her face was that of a woman of three-and-twenty.

The princess was so bewildered with astonishment and admiration that she could hardly thank her, and drew nigh with timidity, feeling dirty and uncomfortable. The lady was seated on a low chair by the side of the fire, with hands outstretched to take her, but the princess hung back with a troubled smile.

'Why, what's the matter?' asked her grandmother. 'You haven't been doing anything wrong--I know that by your face, though it is rather miserable. What's the matter, my dear?' And she still held out her arms.

'Dear grandmother,' said Irene, 'I'm not so sure that I haven't done something wrong. I ought to have run up to you at once when the long-legged cat came in at the window, instead of running out on the mountain and making myself such a fright.' 'You were taken by surprise, my child, and you are not so likely to do it again. It is when people do wrong things wilfully that they are the more likely to do them again. Come.' And still she held out her arms.

'But, grandmother, you're so beautiful and grand with your crown on; and I am so dirty with mud and rain! I should quite spoil your beautiful blue dress.' With a merry little laugh the lady sprung from her chair, more lightly far than Irene herself could, caught the child to her bosom, and, kissing the tear-stained face over and over, sat down with her in her lap.

'Oh, grandmother! You'll make yourself such a mess!' cried Irene, clinging to her.

'You darling! do you think I care more for my dress than for my little girl? Besides--look here.'