CHAPTER 19, part 1

CHAPTER 19

Goblin Counsels

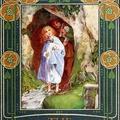

He must have slept a long time, for when he awoke he felt wonderfully restored--indeed almost well--and very hungry. There were voices in the outer cave.

Once more, then, it was night; for the goblins slept during the day and went about their affairs during the night.

In the universal and constant darkness of their dwelling they had no reason to prefer the one arrangement to the other; but from aversion to the sun-people they chose to be busy when there was least chance of their being met either by the miners below, when they were burrowing, or by the people of the mountain above, when they were feeding their sheep or catching their goats. And indeed it was only when the sun was away that the outside of the mountain was sufficiently like their own dismal regions to be endurable to their mole eyes, so thoroughly had they become unaccustomed to any light beyond that of their own fires and torches.

Curdie listened, and soon found that they were talking of himself.

'How long will it take?' asked Harelip.

'Not many days, I should think,' answered the king. 'They are poor feeble creatures, those sun-people, and want to be always eating. We can go a week at a time without food, and be all the better for it; but I've been told they eat two or three times every day! Can you believe it? They must be quite hollow inside--not at all like us, nine-tenths of whose bulk is solid flesh and bone. Yes--I judge a week of starvation will do for him.' 'If I may be allowed a word,' interposed the queen,--'and I think I ought to have some voice in the matter--' 'The wretch is entirely at your disposal, my spouse,' interrupted the king. 'He is your property. You caught him yourself. We should never have done it.' The queen laughed. She seemed in far better humour than the night before.

'I was about to say,' she resumed, 'that it does seem a pity to waste so much fresh meat.' 'What are you thinking of, my love?' said the king. 'The very notion of starving him implies that we are not going to give him any meat, either salt or fresh.' 'I'm not such a stupid as that comes to,' returned Her Majesty. 'What I mean is that by the time he is starved there will hardly be a picking upon his bones.' The king gave a great laugh.

'Well, my spouse, you may have him when you like,' he said. 'I don't fancy him for my part. I am pretty sure he is tough eating.' 'That would be to honour instead of punish his insolence,' returned the queen. 'But why should our poor creatures be deprived of so much nourishment? Our little dogs and cats and pigs and small bears would enjoy him very much.' 'You are the best of housekeepers, my lovely queen!' said her husband.

'Let it be so by all means. Let us have our people in, and get him out and kill him at once. He deserves it. The mischief he might have brought upon us, now that he had penetrated so far as our most retired citadel, is incalculable. Or rather let us tie him hand and foot, and have the pleasure of seeing him torn to pieces by full torchlight in the great hall.'