27. How Leonidas Kept the Pass

"The graves of those who cannot die." —BYRON.

Meanwhile, what were the Greeks doing, to prepare for the Persian invasion? There was at Athens, a certain man, but newly risen into the front rank of the citizens. His name was Themistocles. His idea was to make Athens a sea-state, the strongest sea-state in Greece, if possible. He looked out on the bays and inlets of the coast and realised what good harbours they were. He looked beyond, to the many islands, lying in the Archipelago, all offering shelter and refuge to ships, and he saw that one strong fleet, might protect Greece from the Persians, better than any army she could raise.

A rich bed of silver had just been found in the neighbourhood, and the treasury was very rich; so Themistocles advised the Athenians to spend this sum of money, in building new ships, and at last he persuaded them to listen to him. Before many years had passed, Athens had a fleet of two hundred ships—the most powerful fleet in Greece.

Themistocles had some difficulty in carrying his point, because there was another citizen in Athens, who disapproved of his plan. His name was Aristides, and he was known as the Just, because he was the soul of honour. He thought, that if Athens had beaten the Persians once by land, she might do so again. He thought it was better for the people to improve their army, rather than their navy. For his opposition, he was exiled for ten years from Greece, but he found a way of helping Athens afterwards, which has made his name famous.

It was agreed that the King of Sparta should undertake the defence of a narrow pass which connected North and South Greece together, and through which the Persian army must pass.

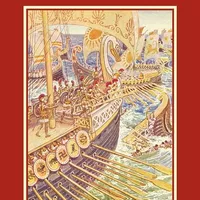

The name of Leonidas, King of Sparta, will ever live in the world's history for his splendid, if hopeless, defence of the Pass of Thermopylæ. With some hundreds of Spartans he marched northwards, to take up the post allotted to him. The pass lay between high mountains and the sea. It was about a mile long. The narrow entrances were known as the Pylæ or Gates, and the whole pass, distinguished for its hot springs, was known as the Pass of the Hot-Gates. The fleet under a Spartan commander, took up its position at the sea end of the pass; the mountain road was kept by some Greeks from a neighbouring state.

The Persians approached. For four days they lay before the pass without attacking, astonished to see the Spartans quietly practising their gymnastics and combing their long hair, as they did before a festival.

"You will not be able to see the sun for the clouds of javelins and arrows," the Persians cried to Leonidas, before they began the attack. "We will fight in the shade then," was his quiet and heroic reply. On the fifth day the Persians attacked, but they met with no success, against the stout-hearted Spartans. Even the choicest of the Persian soldiers, known as the Ten Thousand or the Immortals, made no impression on them.

"Thrice," says the old historian, "the king sprang from his throne in agony for his army." On the third day after the fighting had begun, a native of Greece told Xerxes of a path over the mountain, and at nightfall a strong Persian force was sent to ascend the path and attack the Greeks in the rear. In the early morning the Greeks, at the head of the pass, heard a trampling through the woods. They fled away in terror and the Persians marched on, behind Leonidas.

In the course of the night, Leonidas knew what had happened. He saw that, if he did not retreat at once, he must be surrounded and perish. But the law of Sparta forbade the soldier to leave his post. Leonidas had no fear of death. The other troops went away, but the King of Sparta and his six hundred men resolved to die at their post. The Persians came on, and things became more and more desperate for the Greeks. Leonidas was killed, and one by one the brave Spartans fell around him.

They did not die in vain. It was a moment when the hearts of the Greeks were wavering and men were inclined to forsake country for self, that the Spartan King Leonidas and his Spartan subjects, showed Greece how citizens should do their duty.

At the entrance to the pass the king and his warriors were buried, while these words were engraved in their memory:—

"Go, tell the Spartans, thou that passest by, That here, obedient to their laws, we lie."