15. Life of the Monastery

15. حياة الدير

15. Das Leben des Klosters

15. Vida del monasterio

15. Vie du monastère

15. Vita del monastero

15.修道院の生活

15. Życie klasztoru

15. Vida do Mosteiro

15. Жизнь монастыря

15. Manastır Yaşamı

15. Життя монастиря

15. 修道院的生活

15. 修道院的生活

In the last two chapters we have studied the life of the castle, of the village, and of the town.

||||chapters|||||||||||||||

لقد درسنا في الفصلين الأخيرين حياة القلعة والقرية والمدينة.

In the last two chapters we have studied the life of the castle, of the village, and of the town.

We must now see what the life of the monastery was like.

يجب علينا الآن أن نرى كيف كانت حياة الدير.

We must now see what the life of the monastery was like.

In the Middle Ages men thought that storms and lightning, famine and sickness, were signs of the wrath of God, or were the work of evil spirits.

|||||thought|||||||||||the||||or|were = were||work|||

|||||||||lightning||||||||anger of God|||||||||

||||||||||голод|||||||гнів|||||||||

في العصور الوسطى، اعتقد الناس أن العواصف والبرق والمجاعة والمرض هي علامات غضب الله، أو أنها من عمل الأرواح الشريرة.

The world was a terrible place to them, and the wickedness and misery with which it was filled made them long to escape from it.

||||||||||||||||||||longed||||

||||||||||злість||||||||||||||

كان العالم مكانًا فظيعًا بالنسبة لهم، والشر والبؤس الذي كان يمتلئ به جعلهم يتوقون للهروب منه.

Great numbers, therefore, abandoned the world and became monks, to serve God and save their souls.

ولذلك هجر عدد كبير من العالم وصاروا رهبانًا ليخدموا الله ويخلصوا نفوسهم.

In this way monasteries arose on every hand, and in every Christian land.

|||||on|||||||

وهكذا قامت الأديرة في كل ناحية، وفي كل أرض مسيحية.

It was not long before men began to feel the need of rules to govern the monasteries.

|||a long time|before||||to feel||||||||

ولم يمض وقت طويل حتى بدأ الناس يشعرون بالحاجة إلى قواعد تحكم الأديرة.

If the monks were left each to do what he thought best, there would be trouble of all sorts.

||||||||||||||be||of||

||||||||||||||||||kinds

إذا ترك كل من الرهبان ليفعل ما يعتقد أنه الأفضل، فستكون هناك مشاكل من جميع الأنواع.

A famous monk named Benedict drew up a series of rules for his monastery, and these served the purpose so well that they were adopted for many others.

||||Benedict|||||||||||||||so||||||||

||||Benedict|||||||||||||||||||||||

|||||склав||||||||||||||||||||||

قام راهب مشهور يُدعى بنديكت بصياغة سلسلة من القواعد لديره، وقد خدمت هذه الغرض جيدًا لدرجة أنه تم اعتمادها من قبل العديد من القواعد الأخرى.

A famous monk named Benedict drew up a series of rules for his monastery, and these served the purpose so well that they were adopted for many others.

In course of time the monasteries of all Western Europe were put under "the Benedictine rule," as it was called.

||||||||||||||Benedictine order|||||

وبمرور الوقت، وُضِعَت أديرة أوروبا الغربية كلها تحت "الحكم البنديكتي"، كما كان يُطلق عليه.

The dress of the monks was to be of coarse woolen cloth, with a cowl or hood which could be pulled up to protect the head; and about the waist a cord was worn for a girdle.

|||||was|to||||made of wool||||cowl||||||||||||||||||||||girdle = a belt

||||||||||wool||||hood|||||||||||||||midsection||cord|||||belt or sash

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||帯

||||||||||вовняного||||капюшон||||||||||||||||||||||пояс

كان لباس الرهبان من قماش الصوف الخشن، مع قلنسوة أو غطاء يمكن سحبه لحماية الرأس؛ وحول الخصر كان يلبس حبلًا كحزام.

The gown of the Benedictines was usually black, so they were called "black monks."

|gown|||Benedictine monks|||||||||

|robe|||Benedictine monks|||||||||

||||бенедиктин|||||||||

كان ثوب البينديكتين عادة أسود اللون، لذلك أطلق عليهم اسم "الرهبان السود".

As the centuries went by, new orders were founded, with new rules; but these usually took the rule of St.

|||passed||||||||||||||||

ومع مرور القرون، تأسست أنظمة جديدة بقواعد جديدة؛ ولكن هذه عادة ما تأخذ حكم القديس.

Benedict and merely changed it to meet new conditions.

||only||||||

بنديكت وغيره فقط لتلبية الشروط الجديدة.

In this way arose "white monks," and monks of other names.

||||||||di||

وبهذه الطريقة نشأ "الرهبان البيض" ورهبان بأسماء أخرى.

In addition, orders of "friars" were founded, who were like the monks in many ways, but lived more in the world, preaching, teaching, and caring for the sick.

|||di||||||||||||||||||||||||

||||monks, brothers, clergy|||||||||||||||||preaching||||||ill

||||брати|||||||||||||||||проповідую||||||

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم تأسيس رهبانيات "الرهبان"، الذين كانوا مثل الرهبان في كثير من النواحي، لكنهم عاشوا أكثر في العالم، يبشرون ويعلمون ويهتمون بالمرضى.

These were called "black friars," "gray friars," or "white friars," according to the color of their dress.

these orders|||||||||monks|||||||

||||修道士||||||||||||

||||брати||||||||||||

وكان يُطلق على هؤلاء اسم "الرهبان السود" أو "الرهبان الرماديون" أو "الرهبان البيض" حسب لون ملابسهم.

Besides the orders for men, too, there were orders for women, who were called "nuns"; and in some places nunneries became almost as common as monasteries.

||||||||orders|||||||||||monasteries||||||

|||||||||||||||||||monastic communities||||||

|||||||||||||||||||жіночі монаст||||||

وإلى جانب أوامر الرجال أيضًا، كانت هناك أوامر للنساء، اللاتي أطلق عليهن اسم "الراهبات". وأصبحت أديرة الراهبات في بعض الأماكن شائعة مثلها مثل الأديرة.

Let us try now to see what a Benedictine monastery was like.

دعونا نحاول الآن أن نرى كيف كان شكل الدير البينديكتيني.

One of the Benedict's rules provided that every monastery should be so arranged that everything the monks needed would be in the monastery itself, and there would be no need to wander about outside; "for this," said Benedict, "is not at all good for their souls."

|||Benedict||||||should|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||good|||

|||Benedict||that||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

تنص إحدى قواعد بنديكتوس على أن كل دير يجب أن يتم ترتيبه بحيث يكون كل ما يحتاجه الرهبان موجودًا في الدير نفسه، ولن تكون هناك حاجة للتجول في الخارج؛ قال بنديكتوس: "لأن هذا ليس جيدًا على الإطلاق لأرواحهم".

Each monastery, therefore, became a settlement complete in itself.

|||||community|||

ولذلك أصبح كل دير مستوطنة كاملة في حد ذاته.

It not only had its halls where the monks ate and slept, and its own church; it also had its own mill, its own bake-oven, and its own workshops where the monks made the things they needed.

|||||||||||||||||||||||||baking oven||||craft facilities||||||||

ولم يكن بها فقط قاعاتها التي يأكل فيها الرهبان وينامون، وكنيستها الخاصة؛ كما كان لديها مطحنة خاصة بها، وفرن خبز خاص بها، وورش عمل خاصة بها حيث كان الرهبان يصنعون الأشياء التي يحتاجون إليها.

The better to shut out the world, and to protect the monastery against robbers, the buildings were surrounded by a strong wall.

the|migliore||||||||||||||||||||

ومن الأفضل إغلاق العالم، ولحماية الدير من اللصوص، كانت المباني محاطة بسور قوي.

Outside this lay the fields of the monastery, where the monks themselves raised the grain they needed, or which were tilled for them by peasants in the same way that the lands of the lords were tilled.

|||||||||||||||||||||||for|||||||||||||cultivated

وفي الخارج كانت توجد حقول الدير، حيث كان الرهبان أنفسهم يزرعون الحبوب التي يحتاجون إليها، أو التي يحرثها لهم الفلاحون بنفس الطريقة التي كانت تُفلح بها أراضي النبلاء.

Finally, there was the woodland, where the swine were herded; and the pasture lands, where the cattle and sheep were sent to graze.

|||||dove||swine||herded|||||||||||||to graze

|||||||pigs||gathered together|||||||||||||feed

|||||||豚||群れを作った|||||||||||||草を食む

|||||||свині||збиралися|||||||||||||паслися

وأخيرًا، كانت هناك الغابة حيث تُرعى الخنازير؛ والمراعي التي كانت ترعى فيها الماشية والأغنام.

The amount of land belonging to a monastery was often quite large.

||||owned by|||||||

كانت مساحة الأرض التابعة للدير كبيرة جدًا في كثير من الأحيان.

Nobles and kings frequently gave gifts of land, and the monks in return prayed for their souls.

كثيرًا ما كان النبلاء والملوك يقدمون هدايا من الأراضي، وكان الرهبان في المقابل يصلون من أجل أرواحهم.

Often when the land came into the possession of the monks, it was covered with swamps or forests; but by unwearying labor the swamps were drained and the forests felled; and soon smiling fields appeared where before there was only a wilderness.

||the||||||||||||||||||tireless|||||||||abbattuti||||||dove|before|||||

|||||||||||||||wetlands|||||tireless|||wetlands||reclaimed||||cut down||||||||||||wild area

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||伐採された||||||||||||

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||вирубані||||||||||||

في كثير من الأحيان، عندما أصبحت الأرض في حوزة الرهبان، كانت مغطاة بالمستنقعات أو الغابات؛ ولكن بالعمل الدؤوب جفت المستنقعات وقطعت الغابات؛ وسرعان ما ظهرت الحقول المبتسمة حيث لم يكن هناك سوى برية من قبل.

多くの場合、土地が僧侶の所有になると、沼地や森で覆われていました。しかし、疲れを知らない労働によって、沼は排水され、森は伐採されました。そしてすぐに、以前は荒野しかなかったところに笑顔の畑が現れました。

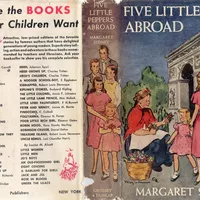

Above is the picture of a German monastery, at the close of the Middle Ages.

أعلاه صورة دير ألماني في نهاية العصور الوسطى.

There we see the strong wall, surrounded by a ditch, inclosing the buildings, and protecting the monastery from attack.

||||||||||surrounding||||||||

|||||||||moat|surrounding and enclosing||||||||

|||||||||ровом|яка оточу||||||||

وهناك نرى السور القوي، محاطًا بخندق، يحيط بالمباني، ويحمي الدير من الهجوم.

To enter the enclosure we must cross the bridge and present ourselves at the gate.

|||enclosure|||||||present||at||

|||fenced area|||||||||||

للدخول إلى المنطقة المسيجة يجب علينا عبور الجسر والوقوف عند البوابة.

When we have passed this we see to the left stables for cattle and horses, while to the right are gardens of herbs for the cure of the sick.

||||||||||||||||||||||medicinal plants||||||

عندما نجتاز هذا نرى على اليسار إسطبلات الماشية والخيول، بينما على اليمين توجد حدائق أعشاب لعلاج المرضى.

Near by is the monks' graveyard with the graves marked by little crosses.

|||||cemetery|||||||

وبالقرب منها توجد مقبرة الرهبان مع قبور مميزة بصلبان صغيرة.

In the center of the enclosure are workshops, where the monks work at different trades.

|||||fenced area|||||||||trades

في وسط السياج توجد ورش عمل حيث يعمل الرهبان في مهن مختلفة.

The tall building with the spires crowned with the figures of saints, is the church, where the monks hold services at regular intervals throughout the day and night.

|||||torri|||the||||||||||||at|||||||

|||||spires|topped with||||||||||||||||regular intervals|||||

والمبنى الشاهق ذو الأبراج المتوجة بأشكال القديسين هو الكنيسة، حيث يقيم الرهبان الصلوات على فترات منتظمة طوال النهار والليل.

Adjoining this, in the form of a square, are the buildings in which the monks sleep and eat.

|||the||||||||||||||

Next to|||||||||||||||||

|||||||||||||ці||||

ويجاور هذا على شكل مربع المباني التي ينام فيها الرهبان ويأكلون.

This is the "cloister," and is the principal part of the monastery.

|||claustro|||||parte|||

|||monastic enclosure||||main||||

|||修道院||||||||

|||клуатр||||||||

هذا هو "الدير" وهو الجزء الرئيسي من الدير.

In southern lands this inner square or cloister was usually surrounded on all sides by a porch or piazza, the roof of which was supported on long rows of pillars; and here the monks might pace to and fro in quiet talk when the duties of worship and labor did not occupy their time.

||||||||||||||||porch|||||||was|||||||||||||||to and fro|||||||||||||||

||||inner courtyard|||cloister|||||||||||veranda|||||||||rows||columns||||||walk back and forth|||back and forth|||||||||||||||

||||||||||||||||||площа|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

في الأراضي الجنوبية، كانت هذه الساحة الداخلية أو الدير محاطة عادة من جميع الجوانب برواق أو ساحة، وكان سقفها مدعومًا بصفوف طويلة من الأعمدة؛ وهنا كان يمكن للرهبان أن يتنقلوا جيئة وذهاباً في حديث هادئ عندما لا تشغل واجبات العبادة والعمل وقتهم.

In addition to these buildings, there are many others which we cannot stop to describe.

وبالإضافة إلى هذه المباني، هناك العديد من المباني الأخرى التي لا نستطيع أن نتوقف عن وصفها.

Some are used to carry on the work of the monastery; some are for the use of the abbot, who is the ruler of the monks; some are hospitals for the sick; and some are guest chambers, where travellers are lodged over night.

||||||||||||are||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

||||||||||||||||||abbott||||||||||||||||||rooms||||housed||

ويستخدم البعض لمواصلة أعمال الدير. وبعضها لاستخدام رئيس الدير، وهو حاكم الرهبان؛ بعضها مستشفيات للمرضى. وبعضها عبارة عن غرف للضيوف يقيم فيها المسافرون ليلاً.

Some are used to carry on the work of the monastery; some are for the use of the abbot, who is the ruler of the monks; some are hospitals for the sick; and some are guest chambers, where travellers are lodged over night.

In the guest chambers the travellers might sleep undisturbed all the night through; but it was not so with the monks.

|||||||||||||but|it||||||

|||rooms|||||uninterrupted, peaceful||||||||||||

|||кімнатах|||||||||||||||||

في غرف الضيوف قد ينام المسافرون دون إزعاج طوال الليل؛ لكن الأمر لم يكن كذلك مع الرهبان.

They must begin their worship long before the sun was up.

يجب أن يبدأوا عبادتهم قبل وقت طويل من شروق الشمس.

Soon after midnight the bell of the monastery rings, the monks rise from their hard beds, and gather in the church, to recite prayers, read portions of the Bible, and sing psalms.

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||psalmi

||||||||||||||||||||||say aloud|||sections||||||sacred songs

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||詩篇

بعد منتصف الليل بقليل يدق جرس الدير، فيقوم الرهبان من أسرّتهم الصلبة، ويجتمعون في الكنيسة، لتلاوة الصلوات، وقراءة أجزاء من الكتاب المقدس، وترتيل المزامير.

Not less than twelve of the psalms of the Old Testament must be read each night at this service.

|||||||||Old|||||||||

||||||||||testament||||||||

يجب قراءة ما لا يقل عن اثني عشر مزمورًا من مزامير العهد القديم كل ليلة في هذه الخدمة.

この礼拝では、毎晩、旧約聖書の詩篇のうち12以上を読まなければなりません。

At daybreak again the bell rings, and once more the monks gather in the church.

|alba|||||||||||||

|dawn|||||||||||||

|світанок|||||||||||||

عند الفجر يقرع الجرس مرة أخرى، ويجتمع الرهبان مرة أخرى في الكنيسة.

This is the first of the seven services which are held during the day.

||||||sette|||||||

هذه هي الأولى من بين الخدمات السبع التي تقام خلال النهار.

The others come at seven o'clock in the morning, at nine o'clock, at noon, at three in the afternoon, at six o'clock, and at bed-time.

||come|||||||||||||||||||||||

|||||||||||||midday||||||||||||

أما الآخرون فيأتون في السابعة صباحًا، وفي التاسعة صباحًا، وفي الظهر، وفي الثالثة بعد الظهر، وفي السادسة صباحًا، وعند وقت النوم.

At each of these there are prayers, reading from the Scriptures, and chanting of psalms.

||||||||||the Scriptures||||

||||||||||holy texts||singing||

وفي كل منها صلاة وقراءة من الكتب المقدسة وترتيل المزامير.

Latin was the only language used in the church services of the West in the Middle Ages; so the Bible was read, the psalms sung, and the prayers recited in this tongue.

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||spoken aloud|||

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||промовляли|||

كانت اللاتينية هي اللغة الوحيدة المستخدمة في خدمات الكنيسة في الغرب في العصور الوسطى. فكان يُقرأ الكتاب المقدس، وتُرتَّل المزامير، وتُتلى الصلوات بهذا اللسان.

The services are so arranged that in the course of every week the entire Psalter or psalm book is gone through; then, at the Sunday night service, they begin again.

|||||||the|||||||psalm book||psalm|||||||||||||

||||||||||||||psalm book||psalm book|||||||||||||

||||||||||||||詩篇|||||||||||||||

||||||||||||||Псалтир|||||||||||||||

يتم ترتيب الخدمات بحيث تتم مراجعة سفر المزامير أو كتاب المزمور بالكامل خلال كل أسبوع؛ ثم، في خدمة ليلة الأحد، يبدأون مرة أخرى.

Besides these services, there are many other things which the monks must do.

وإلى جانب هذه الخدمات، هناك أمور أخرى كثيرة يجب على الرهبان القيام بها.

"Idleness," wrote St.

idleness||

Лінь||

"الكسل"، كتب القديس.

Benedict, "is the enemy of the soul."

بنديكتوس "هو عدو الروح".

So it was arranged that at fixed hours during the day the monks should labor with their hands.

|||||at||||||||||||

||||||||||||||працювати|||

لذلك تم الترتيب أن يعمل الرهبان بأيديهم في ساعات محددة من النهار.

Some plowed the fields, harrowed them, and planted and harvested the grain.

||||harrowed|||||||

|tilled|||broken up|||sowed||||

||||耕された|||||||

||||культивували|||||||

وكان البعض يحرثون الحقول ويتعبونها ويزرعون ويحصدون الحبوب.

Others worked at various trades in the workshops of the monasteries.

|||||||workshops|||

وعمل آخرون في مهن مختلفة في ورش الأديرة.

If any brother showed too much pride in his work, and put himself above the others because of his skill, he was made to work at something else.

|||||||||||||||||||||was|||work|||

فإذا أظهر أي أخ اعتزازًا كبيرًا بعمله، ووضع نفسه فوق الآخرين بسبب مهارته، كان يُجبر على العمل في شيء آخر.

The monks must be humble at all times.

||||modest|||

يجب على الرهبان أن يكونوا متواضعين في كل الأوقات.

"A monk," said Benedict, "must always show humility,—not only in his heart, but with his body also.

||||must|||||||||||||

|||||||humility|||||soul|||||

|||||||скромність||||||||||

قال بنديكتوس السادس عشر: "يجب على الراهب أن يظهر التواضع دائمًا، ليس فقط في قلبه، بل في جسده أيضًا.

This is so whether he is at work, or at prayer; whether he is in the monastery, in the garden, in the road, or in the fields.

This||so||||||||||||||||||||||||

وذلك سواء كان في العمل، أو في الصلاة؛ سواء كان في الدير، أو في البستان، أو في الطريق، أو في الحقول.

Everywhere,—sitting, walking, or standing,—let him always be with head bowed, his looks fixed upon the ground; and let him remember every hour that he is guilty of his sins. "

||||||||to be|||bowed|possessive pronoun indicating ownership by him|looks|||||||||||||||||

|||||||||||bent|||||||||||||||||||

|||||||||||схилено|||||||||||||||||||

في كل مكان، جالسًا أو يمشي أو واقفًا، فليكن دائمًا منحني الرأس ونظراته مثبتة على الأرض؛ وليتذكر كل ساعة أنه مذنب بخطاياه. "

One of the most useful labors which the monks performed was the copying and writing of books.

|||||labors|||||||||||

|||||works|||||||copying||||

|||||праці|||||||||||

وكان من أنفع الأعمال التي كان يقوم بها الرهبان نسخ الكتب وتأليفها.

At certain hours of the day, especially on Sundays, the brothers were required by Benedict's rule to read and to study.

At||||||||||||||Benedict's||||||

في ساعات معينة من اليوم، وخاصة أيام الأحد، كان الإخوة يطلبون، بموجب قاعدة بنديكتوس، القراءة والدراسة.

In the Middle Ages, of course, there were no printing presses, and all books were "manuscript," that is, they were copied a letter at a time by hand.

|||||||||||||||||||||a||||||

|||||||||||||||manuscript|||||duplicated|||||||

في العصور الوسطى، بالطبع، لم تكن هناك مطابع، وكانت جميع الكتب "مخطوطة"، أي أنها كانت تُنسخ حرفًا تلو الآخر يدويًا.

So in each well-regulated monastery there was a writing-room, or "scriptorium," where some of the monks worked copying manuscripts.

|||||||||writing|||scriptorium||||||||

||||well-organized|monastery|||||||writing room||||||||manuscripts

||||||||||||скрипторій||||||||

لذلك كان في كل دير منظم جيدًا غرفة للكتابة، أو "غرفة النسخ"، حيث كان بعض الرهبان يعملون في نسخ المخطوطات.

The writing was usually done on skins of parchment.

||||done||||

||||||||animal skin

وكانت الكتابة تتم عادة على جلود من الرق.

These the monks cut to the size of the page, rubbing the surface smooth with pumice stone.

|||cut = to cut||||||||||||pumice|

||||||||||making|||||pumice stone|

|||||||||||||||軽石|

|||||||||||||||пемза|

يقطع الرهبان هذه القطع بحجم الصفحة، ويفركون السطح ناعمًا بحجر الخفاف.

Then the margins were marked and the lines ruled with sharp awls.

|||||||||||awls

||edges|||||||||pointed tools

|||||||||||尖鋭器

|||||||||||шпильки

ثم تم تحديد الهوامش وتسوية الخطوط بمخارم حادة.

The writing was done with pens made of quills or of reeds, and with ink made of soot mixed with gum and acid.

||||||||penne di uccello||||||||||||||

||||||||feathers|||reeds||||||carbon black|||adhesive substance||acidic substance

||||||||перо|||очеретів||||||сажею|||||кислота

وكانت الكتابة تتم باستخدام الأقلام المصنوعة من الريشات أو القصب، وبحبر مصنوع من السخام الممزوج بالصمغ والحامض.

The greatest care was used in forming each letter, and at the beginning of the chapters a large initial was made.

The|greatest|||||||||||||||||||

||||||||||||||||||initial||

وقد تم بذل أقصى قدر من العناية في تشكيل كل حرف، وفي بداية الفصول تم وضع حرف استهلالي كبير.

Sometimes these initials were really pictures, beautifully "illuminated" in blue, gold, and crimson.

||initials||||||||||crimson

|||||||decorated|||||crimson

||||||||||||багряний

في بعض الأحيان كانت هذه الأحرف الأولى عبارة عن صور، "مضيئة" بشكل جميل باللون الأزرق والذهبي والقرمزي.

All this required skill and much pains.

|||||a lot of|

كل هذا يتطلب مهارة وآلامًا كثيرة.

"He who does not know how to write," wrote one monk at the end of a manuscript, "imagines that it is no labor; but though only three fingers hold the pen, the whole body grows weary."

|||||||||||||||||||it||||||||||||||||疲惫

|||||||||||||||||thinks||||||||||||||||||tired or fatigued

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||疲れる

كتب أحد الرهبان في نهاية إحدى المخطوطات: "إن من لا يعرف الكتابة، يتخيل أن الكتابة ليست عملاً؛ ولكن إذا كانت ثلاثة أصابع فقط تمسك بالقلم، فإن الجسم كله يتعب".

"He who does not know how to write," wrote one monk at the end of a manuscript, "imagines that it is no labor; but though only three fingers hold the pen, the whole body grows weary."

And another one wrote: "I pray you, good readers who may use this book, do not forget him who copied it.

||||||you||||||||||||||

وكتب آخر: "أدعوكم أيها القراء الطيبون الذين يمكنهم استخدام هذا الكتاب، ألا تنسوا من نسخه.

It was a poor brother named Louis, who while he copied the volume (which was brought from a foreign country) endured the cold, and was obliged to finish in the night what he could not write by day. "

||||||||||||||||||||||||was|||||||||||to write||

||||||||||||||||||||suffered through|||||forced to||||||||||||

لقد كان أخًا فقيرًا اسمه لويس، وهو ينسخ المجلد (الذي تم إحضاره من بلد أجنبي) يعاني من البرد، ويضطر إلى إنهاء ما لا يستطيع كتابته في الليل في الليل. "

The monks, by copying books, did a great service to the world, for it was in this way that many valuable works were preserved during the Dark Ages, when violence and ignorance spread, and the love of learning had almost died out.

|||||||||||||it||||||||works||||||||||||||||||||

|||||||||||||||||||||||saved for future||||||forceful conflict||||||||||||

لقد قدم الرهبان، من خلال نسخ الكتب، خدمة جليلة للعالم، لأنه بهذه الطريقة تم الحفاظ على العديد من الأعمال القيمة خلال العصور المظلمة، عندما انتشر العنف والجهل، وكاد حب التعلم أن ينقرض.

In other ways, also, the monks helped the cause of learning.

وبطرق أخرى أيضًا، ساعد الرهبان في قضية التعلم.

In other ways, also, the monks helped the cause of learning.

At a time when no one else took the trouble, or knew how, to write a history of the things that were going on, the monks in most of the great monasteries wrote "annals" or "chronicles" in which events were each year set down.

at||||no|||||||sapevano|||||||the|||were||||||||||||annals|||||||each|||

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||chronicles||chronicles||||||||

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||анали||||||||||

في الوقت الذي لم يتعب فيه أحد أو يعرف كيف يكتب تاريخًا للأشياء التي كانت تحدث، كتب الرهبان في معظم الأديرة الكبرى "حوليات" أو "سجلات" يتم فيها تحديد الأحداث كل عام. تحت.

And at a time when there were no schools except those provided by the Church, the monks taught boys to read and to write, so that there might always be learned men to carry on the work of religion.

|in||time|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||work||

وفي الوقت الذي لم تكن هناك مدارس إلا تلك التي توفرها الكنيسة، كان الرهبان يعلمون الأولاد القراءة والكتابة، ليكون هناك دائمًا رجال متعلمون يقومون بأعمال الدين.

The education which they gave, and the books which they wrote, were, of course, in Latin, like the services of the Church; for this was the only language of educated men.

إن التعليم الذي قدموه، والكتب التي ألفوها، كانت بالطبع باللغة اللاتينية، مثل خدمات الكنيسة؛ لأن هذه كانت اللغة الوحيدة للرجال المتعلمين.

The histories which the monks wrote were, no doubt, very poor ones, and the schools were not very good; but they were ever so much better than none at all.

|||||||||very|||||||||||they|erano||so|much|migliori||||

|accounts||||||||||||||||||||||||||none||

Here is what a monk wrote in the "annals" of his monastery, as the history of the year 807; it will show us something about both the histories and the schools:

وهذا ما كتبه راهب في "حوليات" ديره، كتاريخ سنة 807؛ سيُظهر لنا شيئًا عن التاريخ والمدارس:

"807.

"807.

Grimoald, duke of Beneventum, died; and there was great sickness in the monastery of St.

Grimoald|||Benevento|||||||||||

Grimoald|||Benevento|||||||||||

توفي جريموالد، دوق بينيفينتوم؛ وكان مرض عظيم في دير القديس.

Boniface, so that many of the younger brothers died.

Boniface||||||||

بونيفاس، حتى أن العديد من الإخوة الأصغر سنا ماتوا.

The boys of the monastery school beat their teacher and ran away. "

أولاد مدرسة الدير ضربوا معلمهم وهربوا. "

That is all we are told.

|||||dicono

هذا هو كل ما قيل لنا.

Were the boys just unruly and naughty?

||||||naughty

||||disorderly||

||||||непокірні

هل كان الأولاد مجرد جامحين ومشاغبين؟

Did they rebel at the tasks of school at a time when Charlemagne was waging his mighty wars; and did they long to become knights and warriors instead of priests and monks?

||rebel||||||||||||waging|||||||long||||||||||

||revolt||||||||||||conducting|||||||long||||||||||

||||||||||||||戦争を行っていた|||||||||||||||||

||||||||||||||вів|||||||||||||||||

هل تمردوا على المهام المدرسية في الوقت الذي كان شارلمان يشن فيه حروبه الجبارة؛ وهل اشتاقوا لأن يصبحوا فرسانًا ومحاربين بدلًا من الكهنة والرهبان؟

Or was it on account of the sickness that they ran away?

or|was||a causa de||||||||

||||account|||||||

أم بسبب المرض هربوا؟

We cannot tell.

We||

لا يمكننا أن نقول.

That is the way it is with many things in the Middle Ages.

||||it||||||||

وهذا هو الحال مع أشياء كثيرة في العصور الوسطى.

Most of what we know about the history of that time we learn from the "chronicles" kept by the monks, and these do not tell us nearly all that we should like to know.

إن معظم ما نعرفه عن تاريخ ذلك الوقت نتعلمه من "السجلات" التي يحتفظ بها الرهبان، وهي لا تخبرنا تقريبًا بكل ما نود أن نعرفه.

The three most important things which were required of the monks were that they should have no property of their own, that they should not marry, and that they should obey those who were placed over them.

||||||||||||||should||||||||||||||||||||||

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||підкорятися||||||

وأهم ثلاثة أشياء مطلوبة من الرهبان هي ألا تكون لهم ممتلكات خاصة بهم، وألا يتزوجوا، وأن يطيعوا من هم فوقهم.

The three most important things which were required of the monks were that they should have no property of their own, that they should not marry, and that they should obey those who were placed over them.

"A monk," said Benedict, "should have absolutely nothing, neither a book, nor a tablet, nor a pen."

|||||||||||||writing tablet|||

قال بنديكتوس السادس عشر: "لا ينبغي أن يكون لدى الراهب أي شيء على الإطلاق، لا كتاب ولا لوح ولا قلم".

"A monk," said Benedict, "should have absolutely nothing, neither a book, nor a tablet, nor a pen."

Even the clothes which they wore were the property of the monastery.

||garments|||||||||

وحتى الملابس التي كانوا يرتدونها كانت ملكًا للدير.

If any gifts were sent them by their friends or relatives, they must turn them over to the abbot for the use of the monastery as a whole.

||||||||||||||||||head of the monastery|||||||||the entire monastery

إذا تم إرسال أي هدايا من أصدقائهم أو أقاربهم، فيجب عليهم تسليمها إلى رئيس الدير لاستخدام الدير ككل.

The rule of obedience required that a monk, when ordered to do a thing, should do it without delay; and if impossible things were commanded, he must at least make the attempt.

The|||||||||||||||||||||||||||at||fare||

وقاعدة الطاعة تقضي بأن الراهب، عندما يؤمر بشيء، يجب أن يفعله دون تأخير؛ وإذا أمر بأشياء مستحيلة، فعليه على الأقل أن يقوم بالمحاولة.

The rule about marrying was equally strict; and in some monasteries it was counted a sin even to look upon a woman.

||||||||||||||||||look|||

||||||rigid|||||||||sin||||||

وكانت القاعدة المتعلقة بالزواج صارمة بنفس القدر؛ وفي بعض الأديرة كان حتى النظر إلى امرأة يعتبر خطيئة.

Other rules forbade the monks to talk at certain times of the day and in their sleeping halls.

||prohibited|||||||||||||||sleeping areas

وهناك قواعد أخرى تمنع الرهبان من التحدث في أوقات معينة من اليوم وفي قاعات نومهم.

For fear they might forget themselves at the table, St.

||||forget||a|||it

خوفًا من أن ينسوا أنفسهم على المائدة، قال القديس.

Benedict ordered that one of the brethren should always read aloud at meals from some holy book.

||||||brothers||||||||||

أمر بنديكتوس السادس عشر بأن يقرأ أحد الإخوة دائمًا بصوت عالٍ أثناء تناول الطعام من بعض الكتب المقدسة.

All were required to live on the simplest and plainest food.

|||||||||plainest|

|||||||||most basic|

|||||||||найпростіша|

كان مطلوبًا من الجميع أن يعيشوا على أبسط وأبسط الأطعمة.

The rules, indeed, were so strict, that it was often difficult to enforce them, especially after the monasteries became rich and powerful.

|||||rigid|||||||implement|||||||||

في الواقع، كانت القواعد صارمة للغاية، لدرجة أنه كان من الصعب في كثير من الأحيان تطبيقها، خاصة بعد أن أصبحت الأديرة غنية وقوية.

Then, although the monks might not have any property of their own, they enjoyed vast riches belonging to the monastery as a whole, and often lived in luxury and idleness.

ثم، على الرغم من أن الرهبان ربما لم يكن لديهم أي ممتلكات خاصة بهم، إلا أنهم كانوا يتمتعون بثروات هائلة تخص الدير ككل، وكثيرًا ما عاشوا في ترف وبطالة.

When this happened there was usually a reaction, and new orders arose with stricter and stricter rules.

|||||||||||||more stringent|||

عندما حدث هذا كان هناك عادةً رد فعل، وظهرت أوامر جديدة بقواعد أكثر صرامة.

So we have times of zeal and strict enforcement of the rules, followed by periods of decay; and these, in turn, followed by new periods of strictness.

|we||times|||||||||||||||||||||||rigor

||||||||strict application||||||stages of decline||decline||||||||||rigor

||||||||виконання правил||||||||згасання||||||||||строгості

لذلك، لدينا أوقات من الحماسة والتطبيق الصارم للقواعد، تليها فترات من الانحلال؛ وهذه بدورها تليها فترات جديدة من الصرامة.

This went on to the close of the Middle Ages, when most of the monasteries were done away with.

|went = passed|||||||||||||||done||

واستمر هذا حتى نهاية العصور الوسطى، عندما تم إلغاء معظم الأديرة.

When any one wished to become a monk, he had first to go through a trial.

عندما يرغب أي شخص في أن يصبح راهبًا، عليه أولاً أن يمر بالمحاكمة.

He must become a "novice" and live in a monastery, under its rules, for a year; then if he was still of the same mind, he took the vows of Poverty, Chastity, and Obedience.

||||novizio|||||||||||||||||of||||||||||||

||||beginner||||||||||||||||||||||||vows||Poverty|Purity||

يجب أن يصبح "مبتدئا" ويعيش في الدير، وفقا لقواعده، لمدة عام؛ فإذا كان لا يزال على نفس رأيه، أخذ نذور الفقر والعفة والطاعة.

"From that day forth," says the rule of St.

||day||||||

|||forward in time|||||

"من ذلك اليوم فصاعدا" تقول قاعدة القديس.

Benedict, "he shall not be allowed to depart from the monastery, nor to shake from his neck the yoke of the Rule; for, after so long delay, he was at liberty either to receive it or to refuse it. "

|||||||||||||||||the|yoke||||||||||||||||||||

||||||||||||||||||yoke||||||||delay||was||freedom|||accept it|||||

||||||||||||||||||束縛||||||||||||||||||||

||||||||||||||||||ярмо||||||||||||||||||||

قال بندكتس: "لا يجوز له أن يغادر الدير، ولا أن ينزع نير القانون عن رقبته؛ لأنه، بعد تأخير طويل، أصبح حرًا في قبوله أو رفضه".

ベネディクトは、「彼は修道院を離れることも、規則のくびきを首から振ることも許されない。長い間遅れた後、彼はそれを受け取るか拒否するかのどちらかを自由にしたからである。」

When the monasteries had become corrupt, some men no doubt became monks in order that they might live in idleness and luxury.

|||||debased||||||||||||||||

ولما فسدت الأديرة، لا شك أن بعض الناس أصبحوا رهبانًا لكي يعيشوا في الخمول والترف.

But let us think rather of the many men who became monks because they believed that this was the best way to serve God.

|||think||||||||||||||||||||

ولكن دعونا نفكر بالأحرى في العديد من الرجال الذين أصبحوا رهبانًا لأنهم آمنوا أن هذه هي أفضل طريقة لخدمة الله.

Let us think, in closing, of one of the best of the monasteries of the Middle Ages, and let us look at its life through the eyes of a noble young novice.

دعونا نفكر، في الختام، في واحد من أفضل أديرة العصور الوسطى، ودعونا ننظر إلى حياته من خلال عيون شاب مبتدئ نبيل.

The monastery was in France, and its abbot, St.

وكان الدير في فرنسا ورئيسه القديس.

Bernard, was famous throughout the Christian world, in the twelfth century, for his piety and zeal.

Bernard|||||||||||||piety||

Bernard|||across||||||||||devotion to God||enthusiasm

||||||||||дванадцят|||благочестя||

اشتهر برنارد في العالم المسيحي كله في القرن الثاني عشر بتقواه وغيرته.

Of this monastery the novice writes.

عن هذا الدير يكتب المبتدئ.

"I watch the monks at their daily services, and at their nightly vigils from midnight to the dawn; and as I hear them singing so holily and unwearyingly, they seem to me more like angels than men.

||||||||||||vigils = night watches|||||||||||||holily||without tiring|||||||||

|||||||||||of the night|vigils|||||||||||||sacredly||tirelessly|||||||||

||||||||||||постування|||||||||||||святою||невтомно|||||||||

"أراقب الرهبان في خدماتهم اليومية، وفي سهراتهم الليلية من منتصف الليل إلى الفجر، وعندما أسمعهم يغنون بقداسة ودون كلل، يبدو لي أنهم أشبه بالملائكة أكثر من البشر.

Some of them have been bishops or rulers, or else have been famous for their rank and knowledge; now all are equal, and no one is higher or lower than any other.

|||||||||||||||||||tutti||||||||||||

|||||||||||||||status||||||||||||||||

ومنهم من كان أساقفة أو ولاة، أو اشتهر بمرتبته وعلمه؛ الآن الجميع متساوون، ولا أحد أعلى أو أقل من أي شخص آخر.

I see them in the gardens with the hoe, in the meadows with fork and rake, in the forests with the ax.

||||||||hoe|||||||rake||||||

||||||||garden tool|||meadowlands||fork||rake||||||axe

||||||||лопата|||||||граблі||||||

أراهم في الحدائق مع المعزقة، في المروج بالشوكة والمشعل، في الغابات بالفأس.

When I remember what they have been, and consider their present condition and work, their poor and ill-made clothes, my heart tells me that they are not the dull and speechless beings they seem, but that their life is hid with Christ in the heavens.

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||uninteresting|||||||||||he|||||

عندما أتذكر ما كانوا عليه، وأفكر في حالتهم الحالية وعملهم، وملابسهم الرديئة وسيئة الصنع، يخبرني قلبي أنهم ليسوا كائنات بليدة وصامتة كما يبدون، ولكن حياتهم مستترة مع المسيح في المسيح. السماوات.

"Farewell!

"وداع!

God willing, on the next Sunday after Ascension Day, I too, shall put on the armor of my profession as a monk! "

|||||||Ascensione|||||shall put|||||||||

|||||||Ascension Day||||||||||||||

|||||||Вознесіння||||||||||||||

إن شاء الله، في يوم الأحد التالي بعد عيد الصعود، سأرتدي أنا أيضًا درع مهنتي كراهب! "