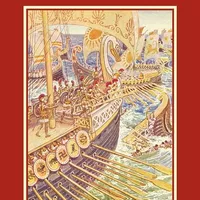

13. King Solomon's Fleet

"And King Solomon made a navy of ships . on the shore of the Red Sea." —1 KINGS ix. 26.

Now when Solomon had finished building the wonderful temple at Jerusalem, he turned his attention to other parts of his dominions. He had learned much from the Phœnicians; he saw the wealth that poured yearly into Tyre, and he felt that a navy for his own people, would greatly tend to improve foreign trade and commerce.

True he had, by his marriage with the daughter of Pharaoh, King of Egypt, improved the trade-routes between the two countries of Egypt and Canaan. But the power of the sea was beginning to make itself felt through the Eastern world, and Solomon appealed to Hiram for help.

Now, the Phœnicians had no port on the shores of the Red Sea, and very gladly Hiram seems to have thrown himself into the scheme for building a new navy for Solomon. To the chosen port, King Solomon travelled himself, to arrange about the making of the fleet. "The Giant's Backbone," as the port was called, was soon teeming with life and activity, shipbuilders from Tyre, and sailors from the land of Phœnicia, were hard at work preparing the new ships, until at last the great fleet was ready to sail forth. Guided by Phœnician pilots, manned by Phœnician sailors, Phœnicians and Israelites sailed forth together on their mysterious voyages, into the southern seas. They sailed to India, to Arabia and Somaliland, and they returned with their ships laden with gold and silver, with ivory and precious stones, with apes and peacocks.

The amount of gold brought to Solomon by his navy was enormous. Silver was so abundant, as to be thought nothing of in those days, and all the king's drinking-cups and vessels were of wrought gold, and every three years his fleet returned with yet more and more gold and silver. For the first time, too, we can see the beginning of contact between the West and East.

"The kings of Tarshish and of the isles shall bring presents," sang the Psalmist. This was from the West, from the Tarshish in Spain, already discovered by the Phœnician sailors, the Tarshish from whence pure silver flowed in glowing streams.

"The kings of Sheba and Seba shall offer gifts," sang the Psalmist again. This was from the East, from the shores of Arabia, from the yet more distant coasts of India, now opened up for the first time in history. "Yea, all kings shall fall down before him; all nations shall serve him." So it was the Phœnicians that taught the Israelites, how to attain all this splendour and riches, insomuch as they taught them the value of the sea.

Now, though the Phœnicians were the first pioneers of the sea, yet they did not neglect their homework. They excelled in bronze work and ivory carving. There are two bronze gates now to be seen in England, carved by these old Phœnicians; they are covered with groups of figures busy with all the occupations of a seaport.

Tyrian dyes, too, were renowned throughout the ancient world. Here is the old story of how they discovered the purple dye.

It was in the old, old days,—so they said,—that one day the nymph Tyros was walking by the sea-shore with Hercules, her beloved. Suddenly her dog broke a small shell with his teeth, and his mouth immediately became dyed with a brilliant red colour. Tyros declared that unless Hercules would procure for her a robe of the same tint, he should see her face no more. Hercules gathered a number of the shells, and having dipped a garment in the blood of the shellfish, he presented it to Tyros, who was henceforth adorned with the royal purple, which throughout all ages has remained the royal colour for British kings and princes.

In mining, too, the Phœnicians were experts. They dug mines in Lebanon—their own mountains—then in the country now known as Rhodesia in South Africa.

While Phœnicia was still at the height of her fame, Hiram, King of Tyre, died. And still to-day, in far-away Syria, a grey weather-beaten tomb of unknown age, raised aloft on three rocky pillars, looks down from the hills above Tyre—looks over the city and over the sea beyond. It is pointed out by the natives, to those who visit the once famous land of Phœnicia, as the "tomb of Hiram."