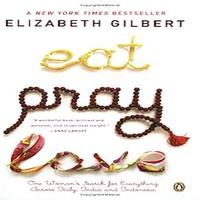

Eat Pray Love ch 30-1

I am so surprised sometimes to notice that my sister is a wife and a mother, and I am not.

Somehow I always thought it would be the opposite. I thought it would be me who would end up with a houseful of muddy boots and hollering kids, while Catherine would be living by herself, a solo act, reading alone at night in her bed. We grew up into different adults than anyone might have foretold when we were children. It's better this way, though, I think. Against all predictions, we've each created lives that tally with us. Her solitary nature means she needs a family to keep her from loneliness; my gregarious nature means I will never have to worry about being alone, even when I am single. I'm happy that she's going back home to her family and also happy that I have another nine months of traveling ahead of me, where all I have to do is eat and read and pray and write. I still can't say whether I will ever want children. I was so astonished to find that I did not want them at thirty; the remembrance of that surprise cautions me against placing any bets on how I will feel at forty. I can only say how I feel now—grateful to be on my own. I also know that I won't go forth and have children just in case I might regret missing it later in life; I don't think this is a strong enough motivation to bring more babies onto the earth. Though I suppose people do reproduce sometimes for that reason—for insurance against later regret. I think people have children for all manner of reasons—sometimes out of a pure desire to nurture and witness life, sometimes out of an absence of choice, sometimes in order to hold on to a partner or create an heir, sometimes without thinking about it in any particular way. Not all the reasons to have children are the same, and not all of them are necessarily unselfish. Not all the reasons not to have children are the same, either, though. Nor are all those reasons necessarily selfish. I say this because I'm still working out that accusation, which was leveled against me many times by my husband as our marriage was collapsing—selfishness. Every time he said it, I agreed completely, accepted the guilt, bought everything in the store. My God, I hadn't even had the babies yet, and I was already neglecting them, already choosing myself over them. I was already a bad mother. These babies—these phantom babies—came up a lot in our arguments. Who would take care of the babies? Who would stay home with the babies? Who would financially support the babies?

Who would feed the babies in the middle of the night? I remember saying once to my friend Susan, when my marriage was becoming intolerable, “I don't want my children growing up in a household like this.” Susan said, “Why don't you leave those so-called children out of the discussion? They don't even exist yet, Liz. Why can't you just admit that you don't want to live in unhappiness anymore? That neither of you does. And it's better to realize it now, by the way, than in the delivery room when you're at five centimeters.” I remember going to a party in New York around that time. A couple, a pair of successful artists, had just had a baby, and the mother was celebrating a gallery opening of her new paintings. I remember watching this woman, the new mother, my friend, the artist, as she tried to be hostess to this party (which was in her loft) at the same time as taking care of her infant and trying to discuss her work professionally. I never saw somebody look so sleep-deprived in my life. I can never forget the image of her standing in her kitchen after midnight, elbows-deep in a sink full of dishes, trying to clean up after this event. Her husband (I am sorry to report it, and I fully realize this is not at all representational of every husband) was in the other room, feet literally on the coffee table, watching TV. She finally asked him if he would help clean the kitchen, and he said, “Leave it, hon—we'll clean up in the morning.” The baby started crying again. My friend was leaking breast milk through her cocktail dress. Almost certainly, other people who attended this party came away with different images than I did. Any number of the other guests could have felt great envy for this beautiful woman with her healthy new baby, for her successful artistic career, for her marriage to a nice man, for her lovely apartment, for her cocktail dress. There were people at this party who would probably have traded lives with her in an instant, given the chance. This woman herself probably looks back on that evening—if she ever thinks of it at all—as one tiring but totally worth-it night in her overall satisfying life of motherhood and marriage and career. All I can say for myself, though, is that I spent that whole party trembling in panic, thinking, If you don't recognize that this is your future, Liz, then you are out of your mind. Do not let it happen. But did I have a responsibility to have a family? Oh, Lord—responsibility. That word worked on me until I worked on it, until I looked at it carefully and broke it down into the two words that make its true definition: the ability to respond. And what I ultimately had to respond to was the reality that every speck of my being was telling me to get out of my marriage. Somewhere inside me an early-warning system was forecasting that if I kept trying to whiteknuckle my way through this storm, I would end up getting cancer. And that if I brought children into the world anyway, just because I didn't want to deal with the hassle or shame of revealing some impractical facts about myself—this would be an act of grievous irresponsibility.