44. The Roman Fleet

"Over the seas our galleys went, With cleaving prows in order brave, To a speeding wind and a bounding wave— A gallant armament." —R. BROWNING.

Hardly had Pyrrhus turned his back for the last time on Italy, when the first note of war, sounded between the Romans, and the men of Carthage. It came from that fair island—the foot of Italy, the Cyclops of the old Argonauts—Sicily. As Pyrrhus disappeared from the Western world he had cried, with his last breath, half in pity, half in envy, "How fair a battlefield are we leaving to the Romans and Carthaginians!" The battlefield for the next hundred years was to be Sicily. Sooner or later, all knew that the struggle must come—the struggle for power between these two great nations. It was not a struggle for Sicily only, it was a contest for the sea—for possession of the blue Mediterranean, that washed the shores of Italy, that carried the ships of Carthage into every known port in Europe and North Africa.

Theirs was the greatest of all islands, the island of Sardinia; theirs the tiny Elba, with its wondrous supply of metals; theirs Malta, the outpost. From the Altar of the Philenæ on the one side to the Pillars of Hercules, on the other, stretched the country of the Carthaginians, the richest land of the ancient world. No wonder, then, they viewed the growing power of Rome with distrust; no wonder they prepared for the struggle, which they knew must come.

The Romans were not so well prepared. Up to this time all their fighting had been by land, they knew nothing of the sea. Great as soldiers, they had not the enterprise, that had prompted the sailors of Tyre and of Carthage, to enlarge the bounds of the world, and to guide their home-made ships into unknown seas.

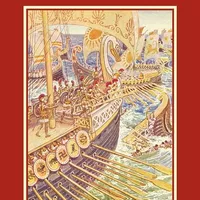

To the Romans, as to the Egyptians, the great salt ocean, was an object of terror. But now the time had come, when the Romans must have a navy. They had some of the old triremes, such as the Greeks used; but they knew that the Carthaginians had newer and better ships at sea, than these old triremes, with their three banks of oars. One day, says an old story, a large ship from Carthage was washed ashore on the coast of Italy. It was a war vessel with sails and five banks of oars. The Romans set to work to copy it. Within sixty days, a growing wood was cut down and built into a fleet of a hundred ships on the new model. While the hundred ships were building, it is said, a large number of Roman landsmen were trained to row on dry land, and in two months the new fleet put to sea.

Never did ships sail under greater difficulties. But with admirable pluck, the sea-sick landsmen pulled their oars, heedless of the starting timbers, of the new unseasoned wood of their vessels. And forth into the Mediterranean, went the Romans against their new foes.

But the skill in naval warfare, which had taken the Carthaginians years and years to learn, could not be mastered by the men of Rome in a day. They devised a new method of naval fighting, by which they could board the enemy's ships and fight hand to hand. It was a clumsy idea, but they won their first sea-fight with the foe. They put up a strong mast, on the front of each ship, to which they lashed a kind of drawbridge, with a sharp spike of strong iron at the end, not unlike the long bill of a raven. When the enemy's ship drew near, they would let this heavy drawbridge fall with a crash, on to the deck of the attacking ship. The iron beak would pierce the planking, and in a few moments the Roman sailors would be on board the Carthaginian ships locked in a hand-to-hand battle.

Off the coast of Sicily the Carthaginians met the clumsy Roman fleet. They bore down upon it, laughing at the strange appearance of the vessels with uncouth masts, and wondering what was hanging on to those masts. Confidently thirty ships of Carthage advanced their decks cleared for action.

What was their surprise then, to find themselves suddenly imprisoned, by the iron beaks, which had excited their contempt, but a short time before. Round swung the fatal raven, pinning the ships together, while the Romans were leaping on to their decks, and fighting them hand to hand. After fifty of their ships of war had been destroyed in this way, the remainder refused to fight any more, and the Romans returned home, having won their first naval victory over the greatest naval Power, the world had yet seen.

A pillar was put up in the Forum, at Rome, adorned with the brazen beaks of the Carthaginian ships, which the clumsy skill of the Romans had enabled them to capture.