Chapter II.

When Charles Crusoe left England, he was such a very young child, that his memory could not furnish him with any recollections beyond a faint idea of his grandpapa, whom he had loved very dearly; but as this affection had been tenderly nursed by his parents, who had in every respect sought to impress him with general love to his country, and particular regard for his family, he was delighted with the thoughts of his voyage. It may, indeed, be supposed, that if England had contained only his beloved mother and sister, he would have rejoiced in the idea of going to them, but to this was added extreme anxiety to see that country, about which all the persons he knew were continually talking, in language which bespoke sorrow for having left it, or desire to return to it. He had been told, that Bombay was more beautiful, that the country was more rich, the fruits finer, the style of living more splendid, and that no people in England were carried about in palanquins, or served by menials, with the profound respect, and implicit obedience, of the natives who attended on him here; but this information had no other effect than to quicken his desire of living there. He remembered that all the little books came from England—that the kind tutor, to whose instruction he was so much indebted for higher knowledge than they had communicated, was English also; so that both early and late recollections pointed to this country, as the source of his highest pleasures. To this might be added, the fixed belief that his own countrymen were the most heroic, learned, and good people in the world; and he naturally desired to behold the land in which they were nurtured, and to become one in a land of which he had been reading and thinking so much.

As Charles had made several short voyages with his parents, during their residence at Bombay, he did not experience much inconvenience from sea-sickness; and he was delighted with the manoeuvring of the ship, which was a noble vessel, called the Alexander, commanded by Captain Gordon, who was a sensible, amiable, and pious man, with whom Mr. Crusoe had been long acquainted. There were not many passengers on board, and several were in a state of bad health, so that the captain's society, when it could be obtained, was more than usually valuable to Mr. Crusoe; but Charles (as might be supposed) found company and amusement more easily, and was soon known and liked by every seaman on board. He had also brought with him his parrot, and a little dog, which had been lately a substitute for his monkey; and a native orphan boy, who had been some years the attendant and playfellow of Charles, accompanied them, as he declared "him heart will break if him no go;" therefore his voyage in every respect promised to be agreeable. As Captain Gordon had some business at Calicut, on the same coast with Bombay, they put in there for a few days, by which means Charles got an opportunity of seeing this city, the capital of a kingdom of the same name, which was at one time so extensive and powerful, that the sovereign took the title of "King of Kings." It was exceedingly reduced by Hyder Ali, who caused the cocoa-nut trees and sandal-wood with which it abounded to be cut down, and the pepper-roots to be pulled up, thereby destroying the natural riches of the land. After his time, Tippoo Saib committed horrid cruelties here, many of which were related to Charles, by persons who had been eyewitnesses of them; and they told him that the city of Calicut, once so flourishing, had now little to support it, except the wood of the teak trees, which is cut down in the neighbouring mountains. These accounts only made him more desirous to reach his native country, and he renewed his voyage with pleasure, hoping that they should stop at the Cape of Good Hope even a shorter time than they had done at Calicut.

On leaving Calicut, they soon came within view of the Laccadive Islands, and the weather being clear and fine, they appeared beautifully spotting the bosom of the ocean, like emeralds on a robe of azure. Mr. Crusoe told Charles that there were no less than thirty of them, that they were covered with trees, and for the most part surrounded with rocks; and that the inhabitants went in flat-bottomed boats to the nearest coast, where they disposed of dried fish and ambergris, and in return got dates and coffee.

"Then," exclaimed Charles, "there is no such thing, it seems, as an uninhabited island? I should like to see one, of all things." "I believe there are several in these seas; but as we are not going on a voyage of discovery, it is not likely we should touch at any of them, unless it is Ascension Isle, which is little better than a barren rock, and would, I fear, not satisfy your curiosity." "No, papa; I should like something to explore; I would have curious plants, and canes, and trickling springs, and beautiful birds, on my islands, and a round hill in the middle, that I might see the extent of my dominions." "I wish I had you at home, my boy; I would find one in the Thames, just to your taste, or perhaps on one of the lakes in Cumberland." Charles thought his papa was laughing at him, and he felt inclined to be angry; but he knew himself to be a little romantic in his notions, and fond of that which was wild and marvellous, so he turned it off with a laugh, saying—"He should not like to be lord of an island no bigger than a compound," which is the name in India for what we call a homestead; on which his father said, with serious approbation in his look—"My dear boy, I perceive you are lord of yourself, which is better than any other power; always pursue this command, and whether you are thrown on a desert island, or a busy world, you will be wise and happy." They now left the Laccadives far behind, and saw around them only the vast ocean, bounded by the skies. Charles thought it a lonely and almost appalling prospect, and sought with more avidity than he had ever done before, that little world within the vessel, which might be called all that remained to its inhabitants. He never failed, however, to watch the sunset, which, under their present situation, for several successive evenings, presented a glorious spectacle. The most gorgeous colours of the rainbow mingled with a flood of golden light, which overspread skies and seas with glory, and even in its departure seemed to give a promise of return.

This magnificent sight never failed to give Charles not only sensations of innocent, but holy delight; he would frequently repeat parts of Thomson's hymn, or the invocation to the sun in the Paradise Lost; and he frequently declared "that it was worth while to endure the monotony of the voyage twice over, for the sake of seeing the sun set so grandly." On the fifth night that they witnessed it, there were symptoms of a wind coming on, by no means of a favourable description, and the pleasure all the passengers had enjoyed in watching it, was exceedingly damped.

The next day proved that their fears were but too well founded; the wind whistling in the cordage, compelled the sailors to reef the sails, and finally agitated the waves, and, apparently, drove the vessel in a clean contrary direction to that in which they sought to steer her. The skies were at this time clear; nevertheless the sun went down unnoticed, save by those who sought, from their observations, to foretell the length of the gale; and so far as Charles could judge, from their looks, the prospect was not favourable. When the waves first began to swell, and the wind to lift up its voice, as it were, in a threatening strain, the boy felt rather pleased than otherwise; for as he had an insatiable curiosity on all points connected with nautical pursuits, he wished to see a storm, and in the wild commotion of the elements, he rather enjoyed the sublimity of the scene than feared its power. The sight of the captain's anxious countenance first drew him from the contemplation of the billows; and when, like the other passengers, he was ordered to leave the deck, he began to question his papa, with much solicitude, as to the probable duration of the storm, and its effects. "I hope, my dear, it will not last long, for we have already been driven considerably out of our track; we are, however, happy in being at a distance from the Maldives, or any other islands; and as we are about crossing the line, I hope we shall soon fall in with another wind, and regain what we have lost." These hopes a few hours afterwards appeared in a likely way to be fulfilled, as there was an evident abatement of the storm; but before another day and night had passed, it was renewed with more fury than before. The ship was now so violently tossed, that every thing on board was in confusion; rain descended in torrents, and there were such frequent storms of thunder and lightning, that they expected destruction every moment. To add to their distress, the captain (who was advanced in years) became so ill, that it was with the utmost difficulty that he did his duty; but his consciousness of the inability of the second in command, induced him to persist in giving orders, and inspecting every thing on board with unceasing vigilance.

In the course of three or four days, their once-beautiful vessel was stripped of sails, masts, and cordage, and reduced to a mere hull, which rolled and plunged, like a huge porpoise, as if it was going to sink, and be no more seen.

When the sun was going down on the sixth night in which they had been thus suffering, one of the sailors espied land, and the captain exerted himself to the utmost to discover where they might be. He concluded, at length, that the island now visible was that of Amsterdam on which he had been many years before, when he went out in the suite of Lord Macartney to China. He said—"The island was formerly a volcano, and was still exceedingly hot, and had no good water upon it; and that there was only one harbour where it was possible to land, therefore he was glad that the wind drove them from it." He owned, however, "that when he had been there, some American seamen were living on the island, for the purpose of collecting seals' skins, as the shores abound with these creatures." On learning this, the crew and passengers became impatient to effect a landing on this island, thinking that any situation must be better than that which they were in; and seeing the ship was utterly unmanageable, they determined on putting to sea in the long-boat, and, if possible, reaching the island by that harbour the captain described. He had said it was only six miles long; and as they had now seen it by an uncertain light for some hours, and were conscious they were drifting from it every moment, they concluded it was possible that they had a chance for life from this effort, which was evidently the only one which remained to them.

The captain, worn out alike with sickness and fatigue, could only declare—"That he would die in his vessel;" and so fully persuaded was Mr. Crusoe that death was inevitable on either hand, that he said—"Himself and son would take their chance with him;" but he gave Sambo, his servant, full liberty to go; and earnestly recommended him to the kindness of those around him. When, however, the poor boy understood what they were about, he protested, that—"Him live with him sahib (master)—him die with him sahib;" and sitting down at his master's feet, he seemed ready to meet the death which threatened him. "You are willing to remain, my dear Charles?" said Mr. Crusoe, questioningly, as he drew his son to his bosom.

"Certainly, certainly!" said the poor boy, as he eagerly embraced his father; "you know what is best, papa: besides, I would not leave you for the world." There was no power of reply to any purpose, for the noise of the wind and sea, the hasty removal of persons into the boat, the shrieks for assistance from some who met a watery grave in their descent, the cries of others for friends or property completed the confusion.

In a short time all were gone, save the four persons we have mentioned, who were now huddled together in the dark, and appeared drifting fast from the land they had seen, towards some other coast; and the captain now recollected the little island of St. Paul, and said—"He apprehended they were near it." Scarcely had he made the remark, when a loud and terrible cry rose on the gale, and they were thus rendered aware of the destruction of their late companions, who had already been swallowed by the raging sea.

Still the billows raged, and every motion of the vessel seemed likely to be her last. Not a word was spoken; but undoubtedly every heart was engaged in prayer, when one sea, more tremendous than the rest, drove them (as it appeared from the shock they received) upon a rock, from which it was evident they were not moved by several succeeding waves.

The captain now suggested the necessity of preserving presence of mind, and gave various directions for their conduct, under the persuasion, that in a few minutes the ship would break in pieces, and, as it were, vanish from under them. This effect did not, however, immediately take place, and in a short time they became sensible that the storm was abating, which left them hope that they might retain their present position till morning.

At length the long-looked-for day rose, and discovered to our shipwrecked friends the situation in which they were placed. The ship was not upon a rock, for there are none round this island, which was indeed that of St. Paul, as the captain had surmised: it was driven, by the violence of the wind, into the deep sandy soil, with such force, that it could never be afterwards moved by the waves, which had made numerous breaches in the sides, into which the water was pouring at the end nearest to the sea. On perceiving this, Mr. Crusoe made haste to procure a plank, to use as a bridge, for them to pass to the land, and proposed immediately that they should take as many things as they could out of the vessel, before they were rendered useless by the encroaching water.

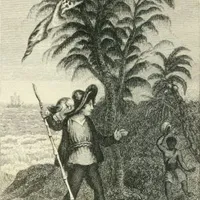

Sambo and Charles lost not a moment in obeying these orders; but the captain was so ill, as to be unable to lend a helping hand; and it was with the utmost difficulty that they could enable him to land, for he was not only worn out with anxiety and fatigue, but under the influence of a consuming fever. Mr. Crusoe's first care was to look for a shady place, on which to spread his bedding, that he might lie down, and, if possible, obtain some repose. At a little distance they found a grassy spot, which formed a glade in a beautiful grove, through which a little limpid stream of pure water ran gurgling towards the ocean. Several birds were already beginning to sing their welcome to the morning, and a cool refreshing breeze ran quivering through the leaves. Every thing around was calm and beautiful, offering a striking contrast with the tremendous storm they had so lately witnessed; and poor Mr. Crusoe observed, with a melancholy smile, to his son—"My dear boy, you have now got a desolate island, and a very pretty one it is, so far as I can see." "It is not desolate, papa, if you are here," said poor Charles, as tears sprung to his eyes. Mr. Crusoe clasped his son in his arms; he thanked God that he was preserved to him, at least for the present; but he thought on his dear wife and daughter, now far distant, and his tears flowed also. Remembering soon, that it was not by thus indulging his feelings that he could assist his friend, and that to him alone must they all look for guidance and protection, he checked his emotion; and when he had seen his sick friend laid down in comparative comfort, he readily assisted the boys in getting all out of the vessel which the late storm had left, which was likely to be of use to them in their present distress.