Chapter IV.

Charles found the labour of walking much less than it had been on the preceding day, because the wet high grass was considerably dried; and when he had proceeded about half a mile, he became sensible that the hurricane which had swept so furiously over one part of the little island, had scarcely touched the other. He had seen many trees blown down, several scathed by the lightning in the beginning of his walk; but as he proceeded, these appearances ceased, and every thing looked the same as it did on the evening when he walked round the island with his father.

It was still very difficult for him to proceed, in his weak state, through the brushwood and grass, without his dear father's arm, and he could not help entertaining many terrible surmises. Though the wind and rain had confined their ravages to one end of the island, the lightning had probably fallen at the other, and his poor father might be, at that moment, a corpse.

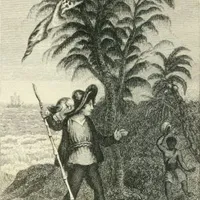

When he emerged from the wood, which completely occupied the middle part of the island (and, as he hoped, approached the spot where his father kept watch), he fired his pistol, and listened with intense anxiety, for some answer. He was too weak to raise a loud halloo, therefore he could only practise this mode of challenge; but his repeated firings gained no attention; and he pushed on in extreme agitation, sometimes running a few yards, at others trembling to such a degree, that he sunk down on the ground, as if he could rather die than proceed any further, lest he should find his father a corpse, and Sambo weeping over him.

At length poor Charles reached the point where his father had proposed to watch. It was evident he had done so, for the sheet was waving from the tree at the farthest end, and a little nearer there was a large stone, which appeared to have been rolled thither, for the sake of forming a seat. Near it lay his father's silk pocket-handkerchief, which he seized with eagerness, crying aloud—"Papa, papa, where are you? speak to me, pray speak to me!" But, alas! no answer was made; this part (though there were some trees) was sufficiently open to shew him that no human being was near.

He now perceived that the soft sand seemed as if it had been trodden by many feet, near the place where he stood; but yet it might be only those of his father, as he walked up and down the beach, looking out for a vessel. This place was so evidently the best in the island for such a purpose, that it was utterly unlikely his father should have removed to any other. It was possible—barely possible—that, worn out with watching, he had returned to the hut, to procure provisions, by one coast of the island, whilst Charles came by the other—"But then, where was Sambo?" At all events, weary and faint as he was, he determined to go round that way; but just as he was leaving the little promontory for that purpose, he perceived a cloak, which Sambo wore in rainy weather (and which it was very probable he had put on, when he went to his father), lying amongst some bushes. What could he think? Had either one, or both of those he had lost, been killed by the lightning, he should have found their remains. There were no wild beasts on the island, so that they could not have been destroyed.—"No! no! in a little time he should see them! He must not allow himself to despair." But it was not a little time, in his present enfeebled and agitated state, that would take the poor boy the circuit he had prescribed himself, though the way was less difficult from impediments than that which he had traversed. He loaded his pistol, took up his staff, and walked forward carefully, as if he feared the creatures which he yet knew the place to be free from. But it was in vain that he looked either towards the beach and the wide expanse of ocean, on the one hand, or among the foliage and high grass on the other! He reached the hut at length, and, alas! it too was empty, and exactly as he had left it.

The sorrow, the very agony of Charles, now knew no bounds. He had lost his father, who was to him his whole world: his desolation and misery was beyond any thing that we can conceive a child to suffer—there is not one of my young readers that could have forborne to cry, if they had seen him thrown on the ground, weeping and wailing for very anguish: he was weak and ill, and had no one to nurse and comfort him; he loved his father with the tenderest affection, and he was torn from him he knew not how; no human being was left on this desolate island, save him now perishing in the cold grave: his situation was desperate and hopeless, beyond all other situations of misfortune and wretchedness.

Last night had been one of wakefulness and sorrow, not unmixed with anger, for he felt that he ought to have been attended to, as being sick; but now no anger blended with his deep, deep affliction. Once it crossed his mind, that perhaps his father had seen a vessel, hailed it, and been taken away by it; but this idea he repelled with scorn and indignation—"No! no!" he cried, "never would my dear good father have forsaken me. He would have died a thousand times first! Besides, where is poor Sambo? why was his cloak left on the shore? Perhaps they ventured to bathe in the sea, or they swam out together to get the boat and they are both lost. Oh that I had died with them!" So extreme was the weakness and exhaustion that the poor child now suffered, from his past illness, long exertion, and violent fits of crying, that he believed he was really going to die; and that God in mercy would remove him, before another day of misery arose upon him. Under this idea, he rose from the ground, to open the cage of the poor parrot, that he might go out and seek for subsistence on the island, when the stock of food be had given him was exhausted. Poll was very sleepy, but Charles, considering it the only living thing that had any interest in him, could not forbear taking it out, and laid down with it in his bosom, commending himself to God, and begging that he might die without pain.

He fell into a profound sleep, the consequence of crying so long, and of the extraordinary exertion he had used. When he awoke, he was sensible of intolerable hunger; and although his miserable situation came by degrees forcibly to his mind, yet nature impelled him to seek eagerly for provision, before he had, as it were, time to reflect on his misery. That source from which he had hitherto been supplied, was now much reduced. The biscuit was nearly finished, and constituted his present meal, with a cup of spring water, into which he put a small portion of the liquor from that flask which he had, the preceding day, taken to support his father, and which they had found in the captain's pocket. It appeared to be of a very strong, but an unpleasant taste, and was most probably a medicine of a restorative quality. Whilst Charles was taking it out of the paper in which it was wrapt, the parrot jumped about him, saying—"Don't be a child," "Don't be a child," and then stalked back into his own cage, and settled himself comfortably, repeating a few Latin words, in a melancholy tone; but from time to time he screamed out—"Don't be a child," vehemently. Charles recollected that these words had often been used by his tutor, when he had shewn an indisposition to his lessons; and he had no doubt but the sight and rustling of the paper had brought them into the bird's memory; nevertheless, they were words which, in his present forlorn state, seemed very applicable. He found, to use his own term, that "he could not die." He remembered that he had once even wished to be placed, like Robinson Crusoe, on a desert island, and find the means of existence solely from his own exertion—"Ah!" cried he, as this thought came into his mind, "I was then a very silly boy: I did not know my obligations to my dear parents, nor our servants, nor even the people amongst whom I lived, since every creature I knew, more or less, contributed to my safety and happiness. I am now punished for my ingratitude and folly. I am left to pine away my life in solitude, to die at least of hunger, without one kind voice to cheer me." "Don't be a child," "Don't be a child," cried the parrot. Poor Charles, who was again weeping bitterly, wiped his eyes, and once more betook him to searching for any vestiges of his father. As before, he obtained no trace of him whatever; but in surveying the coast, he found the boat of which they had been in search, now actually upon the sands, where it had been left by the receding waves. "Had his father and Sambo lost their lives in a vain endeavour to regain this boat?" Again he searched anxiously for their bodies, which, in that case, would, by the same direction of the waves, have been washed on the shore. No vestiges of them were ever found, besides Sambo's cloak, which, it was certain, he would throw off, when he went into the water to assist his master. "Was it not possible that they had recovered the boat, and put to sea, with an intention of fetching him, seeing the boat was considerably nearer to the hut than the little promontory; and that in this situation they had been picked up by some vessel from the neighbouring island: or perhaps they had been driven very far out to sea, in the violence of the storm, and were then taken up by some vessel that could not come for him?" In this thought the poor boy took great comfort; for he was certain that his father would leave no means untried to bring him from the island, when he once reached a port, and had the means of hiring a vessel; and till that time arrived, he thought he could have patience to wait, and courage to endure, the evils of his situation.

He remembered that his papa had repeatedly told him "Never to despair;" that Captain Gordon had said—"It was a chance of a thousand that a single ship should be seen in those seas, for the following three months; but that after that time, many might be expected to navigate within such a distance, as that their signals might be seen; so that if they could make shift to live that time, relief might be confidently expected, especially if they could construct a boat with which to venture out a few leagues:" to which Mr. Crusoe had replied—"With so many birds and hares about us, and the sea into the bargain, we shall surely not want food; and I think we shall manage to make a raft of some kind." "Now I have got a boat!" cried Charles, as these words rose to his mind; and he instantly returned to the hut, where he had still some cordage, though his father had taken a coil of the best with him, when he left him for the last time. It was not without great labour that he at length succeeded in securing the vessel, which he effected, partly by tying her to the strongest tree in the neighbourhood, and partly by filling her with stones and sand from the beach. When this was done, he returned to the hut, lighted a fire, and boiled the last piece of pork he had, in the tea-kettle, which was the only vessel he possessed, capable of such a service.