14. Life of the Village and Town

Leben|||||

|||||Şəhər

14. حياة القرية والمدينة

14. Das Leben im Dorf und in der Stadt

14. Vida del pueblo y de la ciudad

14. Vie du village et de la ville

14. Vita del villaggio e della città

14.村と町の暮らし

14. Het leven in het dorp en de stad

14. Życie wsi i miasta

14. Vida da aldeia e da cidade

14. Жизнь деревни и города

14. Köy ve Kasaba Yaşamı

14. Життя села та міста

14.村镇生活

14. 村莊和城鎮的生活

One thing about the life of the knights and squires has not yet been explained; that is, how they were supported.

Eine|Ding|über|||||Ritter|und|Rittern|hat|nicht|noch|worden|erklärt||||||unterstützt

||||şövalyələrin||||||||||||||||

|||||||||пажі|||||||||||

هناك شيء واحد عن حياة الفرسان ورفاقه لم يتم شرحه بعد؛ أي كيف تم دعمهم.

Jedna věc o životě rytířů a zemanů dosud nebyla vysvětlena; to znamená, jak byly podporovány.

One thing about the life of the knights and squires has not yet been explained; that is, how they were supported.

Одна річ про життя лицарів і зброєносців досі не пояснена, а саме, як вони забезпечувалися.

They neither cultivated the fields, nor manufactured articles for sale, nor engaged in commerce.

|||||||||||||ticarət ilə məş

|weder|bewirtschafteten||Felder|noch|hergestellt|Artikel|||noch|betätigten sich||Handel

||farmed, tended, grew|||||items||||||trade

||обробляли|||||||||||

ولم يزرعوا الحقول، ولا يصنعوا أشياء للبيع، ولا يمارسون التجارة.

Neobdělávali pole, nevyráběli výrobky k prodeji ani se nezabývali obchodem.

They neither cultivated the fields, nor manufactured articles for sale, nor engaged in commerce.

How, then, were they fed and clothed, and furnished with their expensive armor and horses?

||||||||provided with||||||

||||||||||||||atlarla

فكيف تم إطعامهم وكسوتهم وتزويدهم بدروعهم وخيولهم باهظة الثمن؟

How, then, were they fed and clothed, and furnished with their expensive armor and horses?

How, in short, was all this life of the castle kept up,—with its great buildings, its constant wars, its costly festivals, and its idleness?

|||维持|||||||||||||||||||||

||||||||||||||||onun||||||||

||||||||||||||||||||||||бездіяльність

باختصار، كيف تمت المحافظة على كل هذه الحياة في القلعة، بمبانيها العظيمة، وحروبها المستمرة، ومهرجاناتها المكلفة، وكسلها؟

Jak zkrátka vydržel celý tento život hradu - s jeho velkými budovami, neustálými válkami, nákladnými festivaly a nečinností?

How, in short, was all this life of the castle kept up,—with its great buildings, its constant wars, its costly festivals, and its idleness?

We may find the explanation of this in the saying of a bishop who lived in the early part of the Middle Ages.

ولعلنا نجد تفسير ذلك في قول أحد الأساقفة الذي عاش في أوائل العصور الوسطى.

Vysvětlení toho můžeme najít v rčení biskupa, který žil na počátku středověku.

We may find the explanation of this in the saying of a bishop who lived in the early part of the Middle Ages.

"God," said he, "divided the human race from the beginning into three classes.

قال: "لقد قسم الله الجنس البشري منذ البداية إلى ثلاث فئات.

"God," said he, "divided the human race from the beginning into three classes.

There were, the priests, whose duty it was to pray and serve God; the knights, whose duty is was to defend society; and the peasants, whose duty it was to till the soil and support by their labor the other classes."

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||它|||||||||||||

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||work|||

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||праця|||

كان هناك كهنة، واجبهم الصلاة وخدمة الله؛ الفرسان، وواجبهم الدفاع عن المجتمع؛ والفلاحون، الذين كان من واجبهم حرث التربة ودعم الطبقات الأخرى بعملهم.

There were, the priests, whose duty it was to pray and serve God; the knights, whose duty is was to defend society; and the peasants, whose duty it was to till the soil and support by their labor the other classes.

This, indeed, was the arrangement as it existed during the whole of the Middle Ages.

|||||||||the|||||

|||||||existed|||||||

||||угода||||||||||

وكان هذا بالفعل هو الترتيب الذي كان موجودًا طوال العصور الوسطى.

Toto skutečně bylo uspořádání, jaké existovalo po celý středověk.

This, indeed, was the arrangement as it existed during the whole of the Middle Ages.

The "serfs" and "villains" who tilled the soil, together with the merchants and craftsmen of the towns, bore all the burden of supporting the more picturesque classes above them.

||||||||||||||||||||||||||阶层||

|||||||||||||||||bore|||burden|||||charming, attractive, colorful|||

|農奴||農奴|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|||негідники||||||||||||||||||||||живописний|||

وتحمل "الأقنان" و"الأشرار" الذين كانوا يحرثون الأرض، جنبًا إلى جنب مع التجار والحرفيين في المدن، كل عبء إعالة الطبقات الأكثر روعة فوقهم.

„Poddaní“ a „darebáci“, kteří obdělávali půdu, spolu s obchodníky a řemeslníky měst nesli veškeré břemeno podpory malebnějších tříd nad nimi.

The "serfs" and "villains" who tilled the soil, together with the merchants and craftsmen of the towns, bore all the burden of supporting the more picturesque classes above them.

The peasants were called "serfs" and "villains," and their position was very curious.

||||||||||||unusual

كان يُطلق على الفلاحين لقب "الأقنان" و"الأشرار"، وكان موقفهم مثيرًا للفضول للغاية.

Rolníkům se říkalo „nevolníci“ a „darebáci“ a jejich postavení bylo velmi zvědavé.

The peasants were called "serfs" and "villains," and their position was very curious.

For several miles about the castle, all the land belonged to its lord, and was called, in England, his "manor."

||||||||||||||||||他的|

|||||||||||||||||||estate

|||||||||||||||||||маєток

ولعدة أميال حول القلعة، كانت الأرض كلها مملوكة لسيدها، وكانت تسمى في إنجلترا "قصره".

Několik kilometrů od hradu celá země patřila jeho pánovi a v Anglii se jí říkalo „panství“.

For several miles about the castle, all the land belonged to its lord, and was called, in England, his "manor."

He did not own the land outright,—for, as you know, he did homage and fealty for it to his lord or "suzerain," and the latter in turn owed homage and fealty to his "suzerain," and so on up to the king.

||||||||||||||||||||||宗主|||||||||||||||||||

||||||completely and fully|||||||||loyalty or allegiance|||||||overlord|||the latter||||||loyalty, allegiance, fidelity|||overlord||therefore|||||

|||||||||||||||忠誠の誓い|||||||宗主権者|||||||||||||||||||

||||||||||||||||||||||сеньйор|||||||||||||||||||

لم يكن يمتلك الأرض بشكل كامل، لأنه، كما تعلم، قدم الولاء والولاء لسيده أو "سيده"، وهذا الأخير بدوره يدين بالولاء والولاء لـ"سيده"، وهكذا حتى الملك.

Nevlastnil půdu úplně - protože, jak víte, vzdal poctu a věrnost svému pánovi nebo „vrchnosti“ a ten zase svému „vrchnosti“ dlužil poctu a věrnost atd. Král.

He did not own the land outright,—for, as you know, he did homage and fealty for it to his lord or "suzerain," and the latter in turn owed homage and fealty to his "suzerain," and so on up to the king.

他并不完全拥有这片土地,因为,正如你所知,他对他的领主或"上级"进行了效忠和忠诚,而后者又对他的"上级"进行了效忠和忠诚,依此类推直到国王。

Neither did the lord of the castle keep all of the manor lands in his own hands.

ولم يحتفظ سيد القلعة بجميع أراضي القصر في يديه.

Ani pán hradu nedržel všechny panské pozemky ve svých rukou.

Neither did the lord of the castle keep all of the manor lands in his own hands.

城堡的领主也并不是将所有的庄园土地都掌握在自己手中。

He did not wish to till the land himself, so most of it was divided up and tilled by peasants, who kept their shares as long as they lived, and passed them on to their children after them.

|||||||||||||||||||||||portions||||||||||||||

ولم يكن يرغب في فلاحة الأرض بنفسه، فقسمها وفلحها معظمها الفلاحون، الذين احتفظوا بحصصهم طوال حياتهم، ونقلوها إلى أبنائهم من بعدهم.

Nechtěl sám obdělávat půdu, takže většinu z nich rozdělili a obdělávali rolníci, kteří si ponechali své podíly tak dlouho, jak žili, a předávali je svým dětem po nich.

He did not wish to till the land himself, so most of it was divided up and tilled by peasants, who kept their shares as long as they lived, and passed them on to their children after them.

他不想自己耕种土地,因此大部分土地被分给农民耕种,他们只要活着就可以保留自己的份额,并在之后把它们传给自己的孩子。

As long as the peasants performed the services and made the payments which they owed to the lord, the latter could not rightfully turn them out of their land.

||||||||||||||||||||||正当地||||||

|||||||||||financial obligations|||were obligated|||||lord|||legitimately||||||

وطالما أن الفلاحين يؤدون الخدمات ويسددون المبالغ المستحقة عليهم للسيد، فإن هذا الأخير لا يستطيع بشكل قانوني أن يخرجهم من أراضيهم.

Pokud rolníci vykonávali bohoslužby a prováděli platby, které dlužili pánovi, nemohl je právoplatně odvrátit od jejich země.

As long as the peasants performed the services and made the payments which they owed to the lord, the latter could not rightfully turn them out of their land.

The part of the manor which the lord kept in his own hands was called his "domain," and we shall see presently how this was used.

||||||||||||||||domain|||||soon||||

كان الجزء من القصر الذي احتفظ به السيد في يديه يسمى "مملكته"، وسنرى الآن كيف تم استخدام هذا.

Část panství, kterou pán držel ve svých rukou, se nazývala jeho „doménou“, a nyní uvidíme, jak se to používalo.

The part of the manor which the lord kept in his own hands was called his "domain," and we shall see presently how this was used.

In addition there were certain parts which were used by the peasants as common pastures for their cattle and sheep; that is, they all had joint rights in this.

||||||||||||||grazing land|||||||||||shared|||

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، كانت هناك أجزاء معينة يستخدمها الفلاحون كمراعي مشتركة لمواشيهم وأغنامهم؛ أي أن لهم جميعا حقوقا مشتركة في ذلك.

Kromě toho existovaly určité části, které rolníci používali jako běžné pastviny pro svůj dobytek a ovce; to znamená, že v tom měli všichni společná práva.

In addition there were certain parts which were used by the peasants as common pastures for their cattle and sheep; that is, they all had joint rights in this.

Then there was the woodland to which the peasants might each send a certain number of pigs to feed upon the beech nuts and acorns.

|||||||||||||||||||||山毛榉|||

||||forest area|||||||||||||||||beech trees|nuts||acorns

|||||||||||||||||||||буквиця|||жолуді

ثم كانت هناك الغابة التي يمكن لكل فلاح أن يرسل إليها عددًا معينًا من الخنازير لتتغذى على جوز الزان والجوز.

Pak tu byly lesy, do kterých mohli rolníci poslat každý určitý počet prasat, aby se živili bukovými ořechy a žaludy.

Then there was the woodland to which the peasants might each send a certain number of pigs to feed upon the beech nuts and acorns.

Finally there was the part of the manor which was given over to the peasants to till.

وأخيرًا كان هناك الجزء من القصر الذي تم تسليمه للفلاحين لحراثته.

Nakonec tu byla ta část panství, která byla předána rolníkům.

Finally there was the part of the manor which was given over to the peasants to till.

This was usually divided into three great fields, without any fences, walls, or hedges about them.

|||||||||||||bushes, shrubs||

تم تقسيم هذا عادة إلى ثلاثة حقول كبيرة، دون أي سياج أو جدران أو سياج حولها.

This was usually divided into three great fields, without any fences, walls, or hedges about them.

In one of these we should find wheat growing, or some other grain that is sown in the winter; in another we should find a crop of some grain, such as oats, which requires to be sown in the spring; while in the third we should find no crop at all.

|||||||wheat|||||cereal crop|||planted|||||different one|||||||||||oats|||||||||||||||||harvested plant||

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||вівсянка|||||посіяний||||||||||||||

في واحدة منها يجب أن نجد القمح ينمو، أو بعض الحبوب الأخرى التي تزرع في الشتاء؛ وفي مكان آخر يجب أن نجد محصولًا من بعض الحبوب، مثل الشوفان، الذي يجب زراعته في الربيع؛ بينما في الثالثة يجب ألا نجد أي محصول على الإطلاق.

In one of these we should find wheat growing, or some other grain that is sown in the winter; in another we should find a crop of some grain, such as oats, which requires to be sown in the spring; while in the third we should find no crop at all.

The next year the arrangement would be changed, and again the next year.

|||那个|||||||||

وفي العام التالي سيتم تغيير الترتيب، ومرة أخرى في العام التالي.

The next year the arrangement would be changed, and again the next year.

In this way, each field bore winter grain one year, spring grain the next, and the third year it was plowed several times and allowed to rest to recover its fertility.

|||||种植|||||||||||||||耕作||||||||||土壤肥力

|||||||||||crop|||||||||plowed||||||||||soil productivity

وبهذه الطريقة، كان كل حقل يحمل حبوب الشتاء في عام واحد، وحبوب الربيع في العام التالي، وفي السنة الثالثة يتم حرثه عدة مرات ويترك ليرتاح لاستعادة خصوبته.

Tímto způsobem každé pole neslo zimní obilí jeden rok, jarní obilí další a třetí rok bylo několikrát zoráno a necháno odpočívat, aby se obnovila jeho úrodnost.

In this way, each field bore winter grain one year, spring grain the next, and the third year it was plowed several times and allowed to rest to recover its fertility.

While resting it was said to "lie fallow."

|||||||inactive, unused

|||||||休閑地

|||||||пустувати

أثناء الراحة قيل أنه "يرقد".

While resting it was said to "lie fallow."

Then the round was repeated.

|的|||

ثم تكررت الجولة.

This whole arrangement was due to the fact that people in those days did not know as much about "fertilizers" and "rotation of crops" as we do now.

|||是||||||||||||||||||||||||

|||||||||||||||||||plant nutrients||crop rotation||||||

|||||||||||||||||||добрива||||||||

كان هذا الترتيب برمته يرجع إلى حقيقة أن الناس في تلك الأيام لم يكونوا يعرفون الكثير عن "الأسمدة" و"دورة المحاصيل" كما نعرفه الآن.

This whole arrangement was due to the fact that people in those days did not know as much about "fertilizers" and "rotation of crops" as we do now.

The most curious arrangement of all was the way the cultivated land was divided up.

وكان الترتيب الأكثر غرابة على الإطلاق هو الطريقة التي تم بها تقسيم الأراضي المزروعة.

Nejzvědavějším uspořádáním ze všech byl způsob rozdělení obdělávané půdy.

Each peasant had from ten to forty acres of land which he cultivated; and part of this lay in each of the three fields.

每个|||||||||||||||||||||||

|||||||acres|||||farmed|||||was||||||

كان لكل فلاح ما بين عشرة إلى أربعين فدانًا من الأراضي التي يزرعها؛ وجزء من هذا يقع في كل حقل من الحقول الثلاثة.

Každý rolník měl od deseti do čtyřiceti akrů půdy, kterou obdělával; a část toho spočívala v každém ze tří polí.

But instead of lying all together, it was scattered about in long narrow strips, each containing about an acre, with strips of unplowed sod separating the plowed strips from one another.

|||耕作||||||到处|||||||||||||未耕作|草皮|分隔的||||||

||||||||spread|||||sections||having|||||sections||untilled, uncultivated|grass|dividing||||||

||||||||||||||||||||||неораний|газон||||смуги|||

ولكن بدلاً من جمعها معًا، كانت متناثرة في شرائح طويلة وضيقة، تحتوي كل منها على حوالي فدان، مع شرائح من العشب غير المحروث تفصل الشرائح المحروثة عن بعضها البعض.

This was a very unsatisfactory arrangement, because each peasant had to waste so much time in going from one strip to his next; and nobody has ever been able to explain quite clearly how it ever came about.

||||不令人满意|||||||||||||||||||||||||到||||如何|||来|

||||not satisfactory|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

كان هذا ترتيبًا غير مُرضٍ على الإطلاق، لأنه كان على كل فلاح أن يضيع الكثير من الوقت في الانتقال من قطاع إلى آخر؛ ولم يتمكن أحد على الإطلاق من أن يشرح بوضوح تام كيف حدث ذلك.

Bylo to velmi neuspokojivé uspořádání, protože každý rolník musel ztrácet tolik času přechodem z jednoho pásu do druhého; a nikdo nikdy nedokázal zcela jasně vysvětlit, jak k tomu vůbec došlo.

This was a very unsatisfactory arrangement, because each peasant had to waste so much time in going from one strip to his next; and nobody has ever been able to explain quite clearly how it ever came about.

But this is the arrangement which prevailed in almost all civilized countries throughout the whole of the Middle Ages, and indeed in some places for long afterward.

|||||||||||||||||||||||||长时间|

||||||prevailed||||||||||||||||||||

لكن هذا هو الترتيب الذي ساد في جميع البلدان المتحضرة تقريبًا طوال العصور الوسطى بأكملها، بل وفي بعض الأماكن لفترة طويلة بعد ذلك.

Ale toto je uspořádání, které panovalo téměř ve všech civilizovaných zemích po celý středověk, ba na některých místech ještě dlouho poté.

In return for the land which the peasant held from his lord, he owed the latter many payments and many services.

||||||||owned|||||||the lord|||||

وفي مقابل الأرض التي حصل عليها الفلاح من سيده، كان مدينًا لسيده بالعديد من المدفوعات والعديد من الخدمات.

Na oplátku za půdu, kterou rolník vlastnil od svého pána, dlužil druhému mnoho plateb a mnoho služeb.

In return for the land which the peasant held from his lord, he owed the latter many payments and many services.

He paid fixed sums of money at different times during the year; and if his lord or his lord's suzerain knighted his eldest son, or married off his eldest daughter, or went on a crusade, or was taken captive and had to be ransomed,—then the peasant must pay an additional sum.

||||||||||||||||||||封爵|||||||||||||||||被俘||||||赎回||||||||

|||amounts|||||||||||||||||made a knight|||||||||||||||||||||||set free|||||||extra amount|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||викуплений||||||||

كان يدفع مبالغ ثابتة من المال في أوقات مختلفة خلال العام؛ وإذا منح سيده أو سيده ابنه الأكبر لقب فارس، أو تزوج ابنته الكبرى، أو ذهب في حملة صليبية، أو تم أسره وكان لا بد من فدية، فيجب على الفلاح أن يدفع مبلغًا إضافيًا.

Zaplatil pevné částky peněz v různých obdobích roku; a pokud jeho pán nebo vrchní velitel jeho pána pasoval na rytíře svého nejstaršího syna nebo se oženil se svou nejstarší dcerou, nebo šel na křížovou výpravu, nebo byl zajat a musel být vykoupen, - pak musí rolník zaplatit další částku.

At Easter and at other fixed times the peasant brought a gift of eggs or chickens to his lord; and he also gave the lord one or more of his lambs and pigs each year for the use of the pasture.

||||||时刻||||给||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|spring festival|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||пасовище

في عيد الفصح وفي أوقات محددة أخرى، يقدم الفلاح هدية من البيض أو الدجاج إلى سيده؛ وكان أيضًا يعطي للسيد واحدًا أو أكثر من حملانه وخنازيره كل عام لاستخدام المرعى.

Na Velikonoce a v jiné pevné době přinesl rolník svému pánovi dar vajec nebo kuřat; a dal také lordovi každý rok jedno nebo více jehňat a prasat na pastvu.

At harvest time the lord received a portion of the grain raised on the peasant's land.

||||||||||||||农民的|

||||||||||||||peasant|

||||||||||||||селянина|

في وقت الحصاد، كان السيد يتلقى جزءًا من الحبوب المزروعة في أرض الفلاح.

V době sklizně dostal pán část obilí vzneseného na zemi rolníka.

In addition the peasant must grind his grain at his lord's mill, and pay the charge for this; he must also bake his bread in the great oven which belonged to the lord, and use his lord's presses in making his cider and wine, paying for each.

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||压榨|||||||支付||

|||||mill||||||||||||||||make bread||||||||||||||||press||||apple beverage|||||

|||||||||||млин|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

وبالإضافة إلى ذلك، يجب على الفلاح أن يطحن حبوبه في مطحنة سيده، ويدفع رسوم ذلك؛ يجب عليه أيضًا أن يخبز خبزه في الفرن الكبير الذي يخص الرب، ويستخدم معاصر سيده في صنع عصير التفاح والنبيذ، ويدفع ثمن كل منهما.

Kromě toho musí rolník mlít své zrno na mlýně svého pána a zaplatit za to poplatek; musí také upéct svůj chléb ve velké peci, která patřila pánovi, a používat lisy svého pána při výrobě svého moštu a vína, platit za každý.

These payments were sometimes burdensome enough, but they were not nearly so burdensome as the services which the peasants owed their lord.

||||繁重||但是|||||||||||||||

||||heavy, onerous|||||||||||||||||

||||обтяжливими|||||||||||||||||

وكانت هذه المدفوعات في بعض الأحيان مرهقة بما فيه الكفاية، ولكنها لم تكن تقترب من عبئ الخدمات التي يدين بها الفلاحون لسيدهم.

Tyto platby byly někdy dost zatěžující, ale nebyly zdaleka tak zatěžující jako služby, které rolníci dlužili svému pánovi.

All the labor of cultivating the lord's "domain" land was performed by them.

||||farming||||||||

لقد قاموا بكل أعمال زراعة أرض "ملكية" الرب.

Veškerou práci s obděláváním „panské“ půdy pána prováděli oni.

They plowed it with their great clumsy plows and ox-teams; they harrowed it, and sowed it, and weeded it, and reaped it; and finally they carted the sheaves to the lord's barns and threshed them by beating with great jointed clubs or "flails."

||||||笨重的|||牛|牛队||耙平|||播种||||||收割|||||运送||麦束||||||脱粒||||||关节的|||打禾棒

||||||awkward|plowing tools|||||cultivated soil|||planted|||removed weeds|||harvested it|||||||bundles of grain||||storage buildings||separated grain|||striking, hitting|||articulated, segmented|clubs||flail tools

||||||不器用な||||||||||||||||||||||束|||||||||||||||脱穀棒

|||||||плугами||||||||посіяли||||||збирали||||||||||||||||||||||молоти

لقد حرثوها بمحاريثهم الكبيرة وفرق الثيران؛ جرفوه وزرعوه وأزالوا الأعشاب وحصدوا. وأخيرًا حملوا الحزم إلى حظائر اللورد ودرسوها بالضرب بهراوات كبيرة مفاصل أو "المدارس".

Orali to svými velkými neohrabanými pluhy a volskými týmy; zatracovali to a zaseli, vytrhli a vytrhli; a nakonec odvezli snopy do pánových stodol a mlátili je bitím s velkými kloubovými holemi nebo „cepy“.

And when the work was done, the grain belonged entirely to the lord.

|||||||crops|||||

وعندما تم العمل، كانت الحبوب مملوكة بالكامل للرب.

A když byla práce hotová, obilí patřilo výhradně pánovi.

About two days a week were spent this way in working on the lord's domain; and the peasants could only work on their own lands between times.

تم قضاء حوالي يومين في الأسبوع بهذه الطريقة في العمل في مجال السيد؛ ولم يتمكن الفلاحون من العمل إلا في أراضيهم بين الأوقات.

Asi dva dny v týdnu byly tímto způsobem stráveny prací na pánově panství; a rolníci mohli na svých vlastních pozemcích pracovat jen mezitím.

In addition, if the lord decided to build new towers, or a new gate, or to erect new buildings in the castle, the peasants had to carry stone and mortar for the building and help the paid masons in every way possible.

||||||||||||新的||||竖立|||||||||||||砂浆||||||||||||

||||||||||||||||construct|||||||||||||building material||||||||stoneworkers||||

||||||||||||||||звести|||||||||||||розчин||||||||будівельники||||

Kromě toho, pokud se pán rozhodl postavit nové věže nebo novou bránu nebo postavit nové budovy na zámku, rolníci museli nosit kámen a maltu pro stavbu a všemožně pomáhat placeným zedníkům.

And when the demands of their lord were satisfied, there were still other demands made upon them; for every tenth sheaf of grain, and every tenth egg, lamb and chicken, had to be given to the Church as "tithes. "

||||||||||||||征收||他们||||束||||||||||||||||||

|||||||||||||||||||tenth|bundle||||||||||||||||||tithes

||||||||||||||||||||сноп||||||||||||||||||десятини

وعندما تم تلبية طلبات سيدهم، كانت هناك مطالب أخرى مطلوبة منهم؛ لأن كل عشر حزمة من الحبوب، وكل عشر بيضة ولحم ضأن ودجاجة، كان يجب أن تُعطى للكنيسة "كعشور".

A když byly požadavky jejich pána uspokojeny, byly na ně kladeny ještě další požadavky; protože každý desátý svazek obilí a každé desáté vejce, jehněčí a kuřecí maso, muselo být dáno církvi jako „desátky“.

The peasants did not live scattered about the country as our farmers do, but dwelt all together in an open village.

||||居住|||||||||而|||||||

ولم يكن الفلاحون يعيشون مشتتين في أنحاء البلاد كما يفعل مزارعونا، بل كانوا يسكنون معًا في قرية مفتوحة.

Rolníci nežili roztroušeni po zemi tak, jak to dělají naši farmáři, ale přebývali všichni společně v otevřené vesnici.

The peasants did not live scattered about the country as our farmers do, but dwelt all together in an open village.

If we should take our stand there on a day in spring, we should see much to interest us.

|||站立||||||||||||很多|去||

|||||||||||||||||interest|

إذا اتخذنا موقفنا هناك في أحد أيام الربيع، فيجب أن نرى الكثير مما يثير اهتمامنا.

Pokud bychom se tam měli postavit v den jara, měli bychom vidět, co by nás mohlo zajímat.

On the hilltop above is the lord's castle; and near by is the parish church with the priest's house.

|||||||||||||教区||||牧师的|

|||||||||||||church community|||||

||вершина пагорба|||||||||||парафія||||священника|

على قمة التل أعلاه توجد قلعة اللورد. وبالقرب من كنيسة الرعية مع بيت الكاهن.

Na kopci výše je hrad pána; a nedaleko je farní kostel s knězovým domem.

In the distance are the green fields, cut into long narrow strips; and in them we see men plowing and harrowing with teams of slow-moving oxen, while women are busy with hooks and tongs weeding the growing grain.

|||||绿色||||长的|||||||||||耕耘||||缓慢||||||||||||||

||||||||||||||||||cultivating soil||cultivating soil||||||cattle||||||hooks||tongs for weeding|removing weeds|||grain

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||鎌||火ばさみ||||

||||||||||||||||||||боронування||||||воли||||||||щипці||||

في المسافة توجد الحقول الخضراء، مقطعة إلى شرائح ضيقة طويلة؛ وفيها نرى رجالًا يحرثون ويعذبون بمجموعات من الثيران البطيئة الحركة، بينما تنشغل النساء بالخطافات والملقط لإزالة الأعشاب الضارة من الحبوب النامية.

V dálce jsou zelená pole rozřezaná na dlouhé úzké pruhy; a v nich vidíme muže orat a trýznit se s týmy pomalu se pohybujících volů, zatímco ženy mají plné ruce práce s háčky a kleštěmi plující rostoucí obilí.

Close at hand in the village we hear the clang of the blacksmith's anvil, and the miller's song as he carries the sacks of grain and flour to and from the mill.

|||||||听到||锤击声|||铁匠的|铁砧||这个||||||||||||||||

|||||||||clang|||blacksmith's|blacksmith's tool|||miller's||||||bags||||flour|||||

|||||||||カンカン||||金床||||||||||||||||||

|||||||||дзвін|||ковальської|ковадло|||мельника|||||||||||||||

وعلى مقربة من القرية نسمع صوت سندان الحداد، وأغنية الطحان وهو يحمل أكياس الحبوب والدقيق من وإلى الطاحونة.

Po ruce ve vesnici uslyšíme řinčení kovářské kovadliny a mlynářovu píseň, když nese pytle s obilím a moukou do a ze mlýna.

Dogs are barking, donkeys are braying, cattle are lowing; and through it all we hear the sound of little children at play or women singing at their work.

||吠叫|||驴叫|||哞叫|||||||||||||||||||

||||||||mooing|||||||||||||||||||

|||||鳴いている||||||||||||||||||||||

|||||ревіння|||мукають|||||||||||||||||||

الكلاب تنبح، والحمير تناهق، والماشية تخور؛ ومن خلال كل ذلك نسمع صوت الأطفال الصغار وهم يلعبون أو النساء يغنين في عملهن.

Psi štěkají, osli hulákají, dobytek klesá; a přes to všechno slyšíme zvuk malých dětí při hře nebo žen zpívajících při jejich práci.

The houses themselves were often little better than wooden huts thatched with straw or rushes, though sometimes they were of stone.

||||||||||||||芦苇||||是||

||||||||||covered with straw||||reeds||||||

||||||||||з солом'я||соломою||осокою||||||

وكانت المنازل نفسها في كثير من الأحيان أفضل قليلًا من الأكواخ الخشبية المسقوفة بالقش أو نبات السلان، على الرغم من أنها كانت في بعض الأحيان مصنوعة من الحجر.

Samotné domy byly často o něco lepší než dřevěné chatrče s doškovou střechou nebo rákosím, i když někdy byly z kamene.

The houses themselves were often little better than wooden huts thatched with straw or rushes, though sometimes they were of stone.

Even at the best they were dark, dingy, and unhealthful.

即使|在||||||阴暗的||不健康的

|||||||gloomy and dirty||unhealthy

|||||||薄暗くて汚い||

|||||||похмурі||нездорові

حتى في أحسن الأحوال كانت مظلمة وقذرة وغير صحية.

I v tom nejlepším případě byli temní, špinaví a nezdraví.

Chimneys were just beginning to be used in the Middle Ages for the castles of the great lords; but in the peasants' houses the smoke was usually allowed to escape through the doorway.

烟囱||刚刚|开始|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

كانت المداخن قد بدأت للتو في استخدامها في العصور الوسطى لقلاع اللوردات العظماء. لكن في منازل الفلاحين كان يُسمح للدخان عادةً بالخروج عبر المدخل.

Ve středověku se na hradech velkých pánů začaly používat komíny. ale v rolnických domech byl kouř obvykle umožněn uniknout dveřmi.

The door was often made so that the upper half could be left open for this purpose, while the lower half was closed.

|||经常|制作||||||||||||||||||

وكثيراً ما كان الباب يُصنع بحيث يُترك النصف العلوي مفتوحاً لهذا الغرض، بينما يُغلق النصف السفلي.

Dveře byly často vyráběny tak, aby horní polovina mohla být pro tento účel ponechána otevřená, zatímco spodní polovina byla zavřená.

The cattle were usually housed under the same roof with the peasant's family; and in some parts of Europe this practice is still followed.

|livestock|||sheltered|||||||||||||||||||

وعادة ما يتم إيواء الماشية تحت سقف واحد مع أسرة الفلاح؛ ولا تزال هذه الممارسة متبعة في بعض أجزاء أوروبا.

Dobytek byl obvykle umístěn pod stejnou střechou s rolnickou rodinou; a v některých částech Evropy se tato praxe stále dodržuje.

Within the houses we should not find very much furniture.

داخل المنازل لا ينبغي أن نجد الكثير من الأثاث.

V domech bychom neměli najít příliš mnoho nábytku.

Here is a list of the things which one family owned in the year 1345: 2 feather beds, 15 linen sheets, and 4 striped yellow counterpanes.

||||||||||||||羽毛|||||条纹||床罩

||||||||||||||||fabric made from flax|||having stripes||bedspreads

|||||||||||||||||||||縞模様のカバー

||||||||||||||пір'я|||||||покривала

فيما يلي قائمة بالأشياء التي كانت تمتلكها إحدى العائلات في عام 1345: سريرين من الريش، و15 ملاءة من الكتان، و4 ألواح كونترتوب صفراء مخططة.

Zde je seznam věcí, které jedna rodina vlastnila v roce 1345: 2 péřové postele, 15 povlečení a 4 pruhované žluté pokrývky.

1 hand-mill for grinding meal, a pestle and mortar for pounding grain, 2 grain chests, a kneading trough, and 2 ovens over which coals could be heaped for baking.

|||||||||||||||和面槽||||||煤炭|||||

|||milling, crushing|||pestle||||pounding|cereal seeds||||dough preparation|kneading container||ovens|||burning embers|||piled up||baking

||||||乳棒||||||||||こね鉢||||||||||

||||||пестик|||||||||тісто замішування|||||||||||

1 مطحنة يدوية لطحن الدقيق، ومدقة ومدافع هاون لطحن الحبوب، و2 صندوق حبوب، وحوض عجن، و2 فرن يمكن تكديس الفحم فوقهما للخبز.

1 ruční mlýnek na mletí mouky, tlouček na tlučení obilí, 2 truhly na obilí, hnětací žlab a 2 pece, nad nimiž bylo možné ukládat uhlí na pečení.

2 iron tripods on which to hang kettles over the fire; 2 metal pots and 1 large kettle.

|三脚架|||||||||||||

|three-legged stands|||||kettles||||||||

|триноги|||||чайники||||||||

2 حوامل حديدية لتعليق الغلايات فوق النار؛ 2 وعاء معدني وغلاية كبيرة.

2 železné stativy, na které lze pověsit konvice nad oheň; 2 kovové hrnce a 1 velká konvice.

1 metal bowl, 2 brass water jugs, 4 bottles, a copper box, a tin washtub, a metal warming-pan, 2 large chests, a box, a cupboard, 4 tables on trestles, a large table, and a bench.

|||||||||||水槽|||||||||||||支架桌||||||长凳

||||water containers|||copper box||||tin tub||||||||||storage cabinet|||supports for tables||||||a bench

||||||||||||||||||||||||架台||||||

||||глечики|||||||металева праль|||||||||||||на розкладних ніж||||||

1 وعاء معدني، 2 إبريق ماء نحاس، 4 زجاجات، صندوق نحاس، مغسلة صفيح، مقلاة معدنية، 2 خزانة كبيرة، صندوق، خزانة، 4 ترابيزات على حوامل، طاولة كبيرة، ومقعد.

1 kovová mísa, 2 mosazné džbány na vodu, 4 lahve, měděná krabička, plechová vana, kovová ohřívací pánev, 2 velké truhly, krabička, skříň, 4 stoly na podstavcích, velký stůl a lavice.

2 axes, 4 lances, a crossbow, a scythe, and some other tools.

|||弩||镰刀||||

axes|spears||crossbow||sickle-like tool||||

|槍||||鎌||||

2 فأس، 4 رماح، قوس ونشاب، منجل، وبعض الأدوات الأخرى.

The food and clothing of the peasant were coarse and simple, but were usually sufficient for his needs.

||||||||rough and basic||||||adequate|||

وكان طعام الفلاح وملابسه خشنًا وبسيطًا، لكنه كان في العادة كافيًا لاحتياجاته.

At times, however, war or a succession of bad seasons would bring famine upon a district.

|||||一个||||||||||

||||||sequence of events||||||food shortage|||

||||||послідовність|||||||||

ومع ذلك، في بعض الأحيان، قد تؤدي الحرب أو سلسلة من المواسم السيئة إلى جلب المجاعة إلى المنطقة.

Then the suffering would be terrible; for there were no provisions saved up, and the roads were so bad and communication so difficult that it was hard to bring supplies from other regions where there was plenty.

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||areas||||

عندها ستكون المعاناة فظيعة. لأنه لم يكن هناك مخزون من المؤن، وكانت الطرق سيئة للغاية والاتصالات صعبة للغاية لدرجة أنه كان من الصعب جلب الإمدادات من مناطق أخرى حيث يوجد الكثير.

Then the suffering would be terrible; for there were no provisions saved up, and the roads were so bad and communication so difficult that it was hard to bring supplies from other regions where there was plenty.

At such times, the peasants suffered most.

|这样的|时候||||

في مثل هذه الأوقات، عانى الفلاحون أكثر من غيرهم.

At such times, the peasants suffered most.

They were forced to eat roots, herbs, and the bark of trees; and often they died by hundreds for want of even such food.

|||||||||树皮||||||||||缺乏||甚至这样的食物||

|||||roots|plants|||bark||||||||||||||

أُجبروا على أكل الجذور والأعشاب ولحاء الأشجار. وكثيرًا ما كانوا يموتون بالمئات بسبب عدم توفر مثل هذا الطعام.

They were forced to eat roots, herbs, and the bark of trees; and often they died by hundreds for want of even such food.

Thus you will see that the lot of the peasant was a hard one; and it was often made still harder by the cruel contempt which the nobles felt for those whom they looked upon as "base-born."

|||||的|||||||艰难|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Therefore||||||||||||||||||||||||disdain|||||||||||||

||||||||||||||||||||||||軽蔑|||||||||||||

وهكذا سترى أن مصير الفلاح كان صعبًا؛ وكان الأمر يزداد صعوبة في كثير من الأحيان بسبب الازدراء القاسي الذي شعر به النبلاء تجاه أولئك الذين كانوا ينظرون إليهم على أنهم "ولدوا وضيعين".

The name "villains" was given the peasants because they lived in villages; but the nobles have handed down the name as a term of reproach.

||恶棍||||||||||||||||||||||责备的词语

||||||||||||||||||||||||disapproval

||||||||||||||||||||||||非難の言葉

||||||||||||||||||||||||осуд

أطلق اسم "الأشرار" على الفلاحين لأنهم كانوا يعيشون في القرى. لكن النبلاء تناقلوا هذا الاسم كمصطلح عتاب.

In a poem, which was written to please the nobles no doubt, the writer scolds at the villain because he was too well fed, and, as he says, "made faces" at the clergy.

||||||||||||||责骂|||||||||||||||做鬼脸|||

||verse||||||||||||reprimands|||antagonist|||||||||||||||religious leaders

||||||||||||||лає||||||||||||||||||

في قصيدة كتبت لإرضاء النبلاء بلا شك، يوبخ الكاتب الشرير لأنه كان يتغذى جيدًا، وكما يقول، "صنع وجوهًا" لرجال الدين.

"Ought he to eat fish?"

"هل يجب عليه أن يأكل السمك؟"

the poet asks.

|poet|

يسأل الشاعر.

the poet asks.

"Let him eat thistles, briars, thorns, and straw, on Sunday, for fodder; and pea-husks during the week!

|||蓟草|荆棘|||||||饲料|||豌豆壳|||一周

|||thistles|thorny plants|||||||animal feed|||pea shells|||

|||アザミ|いばら|茨||||||飼料||||||

|||чортополохи|терняки|колючки||||||корм||||||

"فليأكل الحسك والشوك والشوك والتبن يوم الأحد علفًا، وقشور البازلاء في أيام الأسبوع!

Let him keep watch all his days, and have trouble.

||||||||有|

يسهر كل أيامه فيجد صعوبة.

Thus ought villains to live.

In this way|should live|||

||злодії||

هكذا يجب أن يعيش الأشرار.

Ought he to eat meats?

هل يجب عليه أن يأكل اللحوم؟

He ought to go naked on all fours, and crop herbs with the horned cattle in the fields! "

|||||||||||||有角的||||

|||||||hands and knees||gather herbs|herbs|||horned||||

|||||||||||||рогатими||||

ينبغي له أن يسير عاريًا على أربع، ويحصد الأعشاب مع الماشية ذات القرون في الحقول! "

He ought to go naked on all fours, and crop herbs with the horned cattle in the fields! "

Of course there were many lords who did not feel this way towards their peasants.

بالطبع كان هناك العديد من اللوردات الذين لم يشعروا بهذه الطريقة تجاه فلاحيهم.

Ordinarily the peasant was not nearly so badly off as the slave in the Greek and Roman days; and often, perhaps, he was as well off as many of the peasants of Europe to-day.

||||||||境况更糟||||||||||||||||好吧||||||||||

usually||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|||||||||||||||||||||||||境遇が悪い|||||||||

ولم تكن حالة الفلاح في العادة في نفس حال العبد في أيام اليونان والرومان؛ وربما كان في كثير من الأحيان في وضع جيد مثل كثير من فلاحي أوروبا اليوم.

But there was this difference between his position and that of the peasant now.

ولكن كان هناك هذا الاختلاف بين موقفه وموقف الفلاح الآن.

Many of them could not leave their lord's manors and move elsewhere without their lord's permission.

||||||||estates|||||||

لم يتمكن الكثير منهم من مغادرة قصور سيدهم والانتقال إلى مكان آخر دون إذن سيدهم.

If they did so, their lord could pursue them and bring them back; but if they succeeded in getting to a free town, and dwelt there for a year and a day without being re-captured, then they became freed from their lord, and might dwell where they wished.

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||居住|||

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||liberated||||||lived, resided|||

|||||||переслідувати|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

إذا فعلوا ذلك، فيمكن لسيدهم أن يلاحقهم ويعيدهم؛ ولكن إذا نجحوا في الوصول إلى مدينة حرة، وسكنوا هناك لمدة عام ويوم دون أن يتم القبض عليهم مرة أخرى، فقد تحرروا من سيدهم، ويمكنهم السكن حيث يريدون.

This brings us to consider now the Towns during the Middle Ages.

这|||||||||||

وهذا يقودنا إلى النظر الآن في المدن خلال العصور الوسطى.

The Germans had never lived in cities in their old homes; so when they came into the Roman Empire they preferred the free life of the country to settling within the town walls.

لم يسبق للألمان أن عاشوا في مدن في منازلهم القديمة؛ لذلك عندما جاءوا إلى الإمبراطورية الرومانية فضلوا الحياة الحرة في البلاد على الاستقرار داخل أسوار المدينة.

The old Roman cities which had sprung up all over the Empire had already lost much of their importance; and under these country-loving conquerors they soon lost what was left.

||||||||||||||||||||||乡村||||||||

||||||emerged||||||||||||||||||victorious rulers||||||

||||||з'явилися||||||||||||||||||||||||

لقد فقدت المدن الرومانية القديمة التي ظهرت في جميع أنحاء الإمبراطورية الكثير من أهميتها بالفعل؛ وسرعان ما فقدوا في ظل هؤلاء الغزاة المحبين للبلاد ما بقي لهم.

In many places the inhabitants entirely disappeared; other places decreased in size; and all lost the right which they had had of governing themselves.

|||||||||||||||||的权利||||||

|||||||||diminished in size||||||||||||||

وفي العديد من الأماكن اختفى السكان تمامًا؛ أماكن أخرى انخفضت في الحجم؛ وفقدوا جميعًا حقهم في حكم أنفسهم.

The inhabitants of the towns became no better off than the peasants who lived in the little villages.

||||||不再|更好||||||||||

ولم يصبح سكان المدن أفضل حالا من الفلاحين الذين يعيشون في القرى الصغيرة.

In both the people lived by tilling the soil.

||||生活||||

وفي كلا الشعبين كان يعيش على حراثة التربة.

In both the lord of the district made laws, appointed officers, and settled disputes in his own court.

|||||||||designated officials||||||||

في كلتا الحالتين، أصدر سيد المنطقة القوانين، وعيّن ضباطًا، وحل النزاعات في محكمته.

There was little difference indeed between the villages and towns, except a difference in size.

ولم يكن هناك فرق يذكر بين القرى والمدن، باستثناء الاختلاف في الحجم.

This was the condition of things during the early part of the Middle Ages, while feudalism was slowly arising, and the nobles were beating back the attacks of the Saracens, the Hungarians, and the Northmen.

这种情况||这个||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|||||||||||||||||||||||repelling|||||||||||

كانت هذه هي حالة الأمور خلال الجزء الأول من العصور الوسطى، بينما كان الإقطاع ينشأ ببطء، وكان النبلاء يصدون هجمات المسلمين والمجريين والشماليين.

At last, in the tenth and eleventh centuries, as we have seen, this danger was overcome.

وأخيراً، في القرنين العاشر والحادي عشر، كما رأينا، تم التغلب على هذا الخطر.

Now men might travel from place to place without constant danger of being robbed or slain.

|||旅行|||||||危险|||||

الآن يمكن للناس أن يسافروا من مكان إلى آخر دون التعرض لخطر السرقة أو القتل.

Commerce and manufacturers began to spring up again, and the people of the towns supported themselves by these as well as by agriculture.

Trade||producers||||||||||||||||||||farming activities

وبدأت التجارة والصناعة في الظهور من جديد، وكان سكان المدن يعولون أنفسهم من خلال هذه المنتجات وكذلك من الزراعة.

With commerce and manufactures, too, came riches.

|||manufacturing industries|||

ومع التجارة والمصنوعات جاءت الثروات أيضًا.

This was especially true in Italy and Southern France, where the townsmen were able by their position to take part in the trade with Constantinople and Egypt, and also to gain money by carrying pilgrims and Crusaders in their ships to the Holy Land.

||||||||||||能够|能够||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

كان هذا صحيحًا بشكل خاص في إيطاليا وجنوب فرنسا، حيث كان سكان المدن قادرين بحكم موقعهم على المشاركة في التجارة مع القسطنطينية ومصر، وكذلك كسب المال عن طريق نقل الحجاج والصليبيين في سفنهم إلى الأراضي المقدسة.

With riches, too, came power; and with power came the desire to free themselves from the rule of their lord.

ومع الثروات أيضاً جاءت السلطة؛ ومع القوة جاءت الرغبة في تحرير أنفسهم من حكم سيدهم.

So, all over civilized Europe, during the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries, we find new towns arising, and old ones getting the right to govern themselves.

وعلى هذا ففي كل أنحاء أوروبا المتحضرة، خلال القرون الحادي عشر والثاني عشر والثالث عشر، نجد مدناً جديدة تنشأ، وتحصل المدن القديمة على الحق في حكم نفسها بنفسها.

In Italy the towns gained power first; then in Southern France; then in Northern France; and then along the valley of the river Rhine, and the coasts of the Baltic Sea.

||||||||||||||||||||||||||shorelines||||

وفي إيطاليا اكتسبت المدن السلطة أولاً؛ ثم في جنوب فرنسا؛ ثم في شمال فرنسا؛ ثم على طول وادي نهر الراين وسواحل بحر البلطيق.

Sometimes the towns bought their freedom from their lords; sometimes they won it after long struggles and much fighting.

وكانت المدن في بعض الأحيان تشتري حريتها من أسيادها؛ في بعض الأحيان فازوا بها بعد صراع طويل وكثير من القتال.

Sometimes the nobles and clergy were wise enough to join with the townsmen, and share in the benefits which the town brought; sometimes they fought them foolishly and bitterly.

||||||||||||||||||||||||||愚蠢地||

||||clergy|||||||||||||advantages|||||||||||

وكان النبلاء ورجال الدين في بعض الأحيان يتمتعون بالحكمة الكافية للانضمام إلى سكان المدينة، والمشاركة في المنافع التي تجلبها المدينة؛ وفي بعض الأحيان كانوا يحاربونهم بحماقة ومرارة.

In Germany and in Italy the power of the kings was not great enough to make much difference one way or the other.

||||||||||是|||||使得|||一个||||

في ألمانيا وإيطاليا، لم تكن قوة الملوك كبيرة بما يكفي لإحداث فرق كبير بطريقة أو بأخرى.

In France the kings favored the towns against their lords, and used them to break down the power of the feudal nobles.

||||supported|||||||||||||||||

وفي فرنسا، فضل الملوك المدن على أسيادها، واستخدموها لكسر سلطة النبلاء الإقطاعيين.

Then, when the king's power had become so strong that they no longer feared the nobles, they checked the power of the towns lest they in turn might become powerful and independent.

ثم، عندما أصبحت قوة الملك قوية جدًا لدرجة أنهم لم يعودوا يخافون النبلاء، قاموا بكبح قوة المدن خشية أن تصبح بدورها قوية ومستقلة.

Thus, in different ways and at different times, there grew up the cities of medieval Europe.

Therefore|||||||||||||||

وهكذا، وبطرق مختلفة وفي أوقات مختلفة، نشأت مدن أوروبا في العصور الوسطى.

In Italy there sprang up the free cities of Venice, Florence, Pisa, Genoa, and others, where scholars and artists were to arise and bring a new birth to learning and art; where, also, daring seamen were to be trained, like Columbus, Cabot, and Vespucius, to discover, in later times, the New World.

|||||||||||比萨|热那亚|||||||将要||||带来|||||学习|||||||||||||卡博特||维斯普奇|||||时代|||

|||emerged|||||||Florence|Pisa|||||intellectuals||creators||||||||||||||||sailors|||||||John Cabot||Vespucci||||||||

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||мореплавці|||||||||||||||||

ونشأت في إيطاليا المدن الحرة مثل البندقية، وفلورنس، وبيزا، وجنوة، وغيرها، حيث نشأ العلماء والفنانون وأنتجوا ميلاداً جديداً للعلم والفن؛ حيث كان من المقرر أيضًا تدريب البحارة الجريئين، مثل كولومبوس، وكابوت، وفيسبوسيوس، لاكتشاف العالم الجديد في أوقات لاحقة.

In France the citizens showed their skill by building those beautiful Gothic cathedrals which are still so much admired.

|||||||||||||||||非常|

||||||||||||cathedrals||||||appreciated

وفي فرنسا، أظهر المواطنون مهارتهم من خلال بناء تلك الكاتدرائيات القوطية الجميلة التي لا تزال تحظى بإعجاب كبير.

In the towns of Germany and Holland clever workmen invented and developed the art of printing, and so made possible the learning and education of to-day.

||||||||craftsmen|created||||||printing press|||||||||||

وفي مدن ألمانيا وهولندا، اخترع العمال الأذكياء فن الطباعة وطوروه، ومن ثم جعلوا التعلم والتعليم في يومنا هذا ممكنين.

The civilization of modern times, indeed, owes a great debt to these old towns and their sturdy inhabitants.

||||||欠|||||||||||

||||||is indebted to||||||||||strong and resilient|

إن حضارة العصر الحديث تدين في الواقع بدين كبير لهذه المدن القديمة وسكانها الأقوياء.

Let us see now what those privileges were which the townsmen got, and which enabled them to help on the world's progress so much.

|||现在|什么||特权|是||||||||||帮助||||||

||||||benefits, rights|||||||||||||||||

دعونا نرى الآن ما هي تلك الامتيازات التي حصل عليها سكان المدينة، والتي مكنتهم من المساعدة في تقدم العالم كثيرًا.

To us these privileges would not seem so very great.

بالنسبة لنا، لا تبدو هذه الامتيازات عظيمة جدًا.

In hundreds of towns in France the lords granted only such rights as the following:

في مئات المدن في فرنسا، منح اللوردات الحقوق التالية فقط:

1\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\.

1\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\ \\\\\\\\\\\\\\.

The townsmen shall pay only small fixed sums for the rent of their lands, and as a tax when they sell goods, etc.

||||||||||||||||||||||and so on

|мешканці міст|||||||||||||||||||||

يجب على سكان المدن أن يدفعوا فقط مبالغ صغيرة ثابتة مقابل إيجار أراضيهم، وكضريبة عند بيع البضائع، وما إلى ذلك.

2\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\.

They shall not be obliged to go to war for their lord, unless they can return the same day if they choose.

ولن يضطروا إلى خوض الحرب من أجل سيدهم، إلا إذا تمكنوا من العودة في نفس اليوم إذا اختاروا ذلك.

3\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\.

3\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\ \\\\\\\\\\\\\\.

When they have law-suits, the townsmen shall not be obliged to go outside the town to have them tried.

||||诉讼|||||||||||||进行||审理

|||||||||||||||||||resolved in court

وعندما تكون لديهم دعاوى قضائية، لا يجوز إلزام سكان المدينة بالخروج إلى خارج المدينة لمحاكمتهم.

4\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\.

4\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\ \\\\\\\\\\\\\\.

No charge shall be made for the use of the town oven; and the townsmen may gather the dead wood in the lord's forest for fuel.

|||||||||||||||||||||||||fuel

لا يجوز فرض أي رسوم مقابل استخدام فرن المدينة؛ ويمكن لسكان المدينة جمع الأخشاب الميتة في غابة اللورد للحصول على الوقود.

5\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\.

The townsmen shall be allowed to sell their property when they wish, and leave the town without hindrance from the lord.

|||||||||||||||||obstruction or interference|||

يُسمح لسكان المدينة ببيع ممتلكاتهم عندما يرغبون في ذلك، ومغادرة المدينة دون عائق من الرب.

6\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\.

Any peasant who remains a year and a day in the town, without being claimed by his lord, shall be free.

||||||||||||||asserted ownership of||||||

أي فلاح يبقى سنة ويومًا في المدينة، دون أن يطالبه سيده، يكون حرًا.

In other places the townsmen got in addition the right to elect their own judges; and in still others they got the right to elect all their officers.

|||||获得了|||||||||||||其他地方|||||||||

||||||||||||||judges|||||||||||||

وفي أماكن أخرى، حصل سكان المدن أيضًا على حق انتخاب قضاتهم؛ وفي حالات أخرى كان لهم الحق في انتخاب جميع ضباطهم.

Towns of this latter class were sometimes called "communes."

||||||||公社

||||||||communes

|||остання|||||комуни

كانت مدن هذه الفئة الأخيرة تسمى أحيانًا "البلديات".

Over them the lord had very little right, except to receive such sums of money as it was agreed should be paid to him.

لم يكن للسيد عليهم سوى القليل من الحقوق، باستثناء الحصول على المبالغ المالية التي تم الاتفاق على دفعها له.

In some places, as in Italy, these communes became practically independent, and had as much power as the lords themselves.

||地方|||||||||||||||||

وفي بعض الأماكن، كما هو الحال في إيطاليا، أصبحت هذه البلديات مستقلة عمليا، وكان لها من السلطة ما يعادل نفوذ اللوردات أنفسهم.

They made laws, and coined money, and had their vassals, and waged war just as the lords did.

||||minted|||||||conducted war||||||

لقد وضعوا القوانين، وسكوا النقود، وكان لهم أتباعهم، وشنوا الحرب كما فعل اللوردات.

But there was this important difference: in the communes the rights belonged to the citizens as a whole, and not to one person.

ولكن كان هناك هذا الاختلاف المهم: في الكوميونات كانت الحقوق تعود إلى المواطنين ككل، وليس إلى شخص واحد.

This made all the citizens feel an interest in the town affairs, and produced an enterprising, determined spirit among them.

|||||||||||||||adventurous|resolute, steadfast, driven|||

وقد جعل هذا الأمر يشعر جميع المواطنين باهتمامهم بشؤون المدينة، وأنتج روح المبادرة والعزم بينهم.

At the same time, the citizens were trained in the art of self-government in using these rights.

|||||||||这个||||||||

|||||||educated||||||||||

وفي الوقت نفسه تم تدريب المواطنين على فن الحكم الذاتي في استخدام هذه الحقوق.

In this way the world was being prepared for a time when governments like ours, "of the people, for the people, and by the people," should be possible.

وبهذه الطريقة كان العالم يستعد لوقت حيث من الممكن أن تكون هناك حكومات مثل حكومتنا، "من الشعب، ومن أجل الشعب، ومن الشعب".

But this was to come only after many, many years.

||将|要|来|||||

ولكن هذا لن يأتي إلا بعد سنوات عديدة.

The townsmen often used their power selfishly, and in the interest of their families and their own class.

||||||自私地|||||||||||

||||||for their own benefit|||||||||||

||||||егоїстично|||||||||||

غالبًا ما استخدم سكان المدينة قوتهم بأنانية ولصالح أسرهم وطبقتهم.

Often the rich and powerful townsmen were as cruel and harsh toward the poorer and weaker classes as the feudal lords themselves.

||||||||||cruel and severe|||||||||||

|||||||||||по відношенню||||||||||

في كثير من الأحيان كان سكان المدن الأغنياء والأقوياء قاسيين وقساة تجاه الطبقات الفقيرة والضعيفة مثل اللوردات الإقطاعيين أنفسهم.

Fierce and bitter struggles often broke out in the towns, between the citizens who had power, and those who had none.

وكثيرًا ما كانت تندلع صراعات عنيفة ومريرة في المدن، بين المواطنين الذين يملكون السلطة، وأولئك الذين لا يملكون أي سلطة.

Often, too, there were great family quarrels, continued from generation to generation, like the one which is told of in Shakespeare's play, "Romeo and Juliet."

经常||||||||||到||||||||||莎士比亚的||罗密欧||朱丽叶

وفي كثير من الأحيان، كانت هناك أيضًا مشاجرات عائلية كبيرة، تستمر من جيل إلى جيل، مثل تلك التي رويت في مسرحية شكسبير "روميو وجولييت".

In Italy there came in time to be two great parties called the "Guelfs" and the "Ghibellines."

|||出现||||||||||教皇派|||吉贝林党

|||||||||||||Guelfs|||Ghibellines

وفي إيطاليا جاء في الوقت المناسب أن يكون هناك حزبان عظيمان يطلق عليهما "الجيلفيون" و"الغيبلينيون".

At first there was a real difference in views between them; but by and by they became merely two rival factions.

||||||||||||||||||||groups

||||||||||||||||||||фракції

في البداية كان هناك اختلاف حقيقي في وجهات النظر بينهما؛ ولكن بمرور الوقت أصبحوا مجرد فصيلين متنافسين.

At first there was a real difference in views between them; but by and by they became merely two rival factions.

Then Guelfs were known from Ghibellines by the way they cut their fruit at table; by the color of roses they wore; by the way they yawned, and spoke, and were clad.

||是||||||||切|||||||||||||||||||||

||||||||||||||||||||||||||opened their mouths|||||dressed, attired

ثم عرف الجلفيون من الغيبلينيين بالطريقة التي يقطعون بها فواكههم على المائدة؛ بلون الورد الذي كانوا يرتدونه؛ من الطريق تثاءبوا وتكلموا وارتدوا ملابس.

Often the struggles and brawls became so fierce in a city that to get a little peace the townsmen would call in an outsider to rule over them for a while.

||||斗殴||||||||以获得||||||||请召唤||||||||||

||||fights or riots||||||||||||tranquility|||||||foreigner|||||||

||||乱闘||||||||||||||||||||||||||

||||бійки||||||||||||||||||||||||||

في كثير من الأحيان، أصبحت الصراعات والمشاجرات شرسة للغاية في المدينة، لدرجة أنه للحصول على القليل من السلام، كان سكان المدينة يستعينون بشخص غريب ليحكمهم لفترة من الوقت.

With the citizens so divided among themselves, it will not surprise you to learn that the communes everywhere at last lost their independence.

|||如此|||||||||||||||||||

مع انقسام المواطنين فيما بينهم، لن يفاجئك أن تعلم أن البلديات في كل مكان فقدت استقلالها أخيرًا.

They passed under the rule of the king, as in France; or else, as happened in Italy, they fell into the power of some "tyrant" or local lord.

||||||||||||||||||||||||暴君|||

لقد مروا تحت حكم الملك كما في فرنسا. وإلا، كما حدث في إيطاليا، فقد وقعوا في قبضة "طاغية" أو سيد محلي.

But let us think, not of the weaknesses and mistakes of these old townsmen, but of their earnest, busy life, and its quaint surroundings.

|||||||vulnerabilities||||||||||serious and sincere|||||charmingly unusual|environment, setting

||||||||||||||||||||||風変わりな|

||||||||||||||||||||||колоритні|

ولكن دعونا نفكر، ليس في نقاط ضعف وأخطاء هؤلاء السكان القدامى، ولكن في حياتهم الجادة والمزدحمة، والمناطق المحيطة بها الغريبة.

但让我们思考这些老城镇人的脆弱和错误,而是他们认真忙碌的生活及其独特的环境。

Imagine yourself a peasant lad, fleeing from your lord or coming for the first time to the market in the city.

||||||||||来到||||||||||

|||||running away|||||||||||||||

تخيل نفسك فلاحًا يهرب من سيدك أو يأتي لأول مرة إلى سوق المدينة.

Imagine yourself a peasant lad, fleeing from your lord or coming for the first time to the market in the city.

想象一下你是一个农民少年,逃离你的领主或第一次来到城里的市场。

As we approach the city gates we see that the walls are strong and crowned with turrets; and the gate is defended with drawbridge and portcullis like the entrance to a castle.

||||||||||||||||塔楼|||||||||||||||

||approach||||||||||||||turrets|||||||||||||||

|||||||||||||||||||||||||落とし格子||||||

||||||||||||||||башточки|||||||||||||||

عندما نقترب من أبواب المدينة نرى أن الأسوار قوية ومتوجة بالأبراج. ويتم الدفاع عن البوابة بجسر متحرك وبوابة مثل مدخل القلعة.

当我们接近城门时,我们看到城墙坚固并 adorned with turrets; 而大门则用吊桥和落屑防御,就像一座城堡的入口。

Within, are narrow, winding streets, with rows of tall-roofed houses, each with its garden attached.

||||||lines|||tall-roofed||||||connected

|||звивисті|||||||будинки|||||

وفي الداخل، توجد شوارع ضيقة ومتعرجة، بها صفوف من المنازل ذات الأسطح العالية، ولكل منها حديقته الملحقة.

The houses themselves are more like our houses to-day than like the Greek and Roman ones; for they have no courtyard in the interior and are several stories high.

||||||||||||||||||||||||inside space|||||

والبيوت نفسها تشبه بيوتنا اليوم أكثر من بيوتنا اليونانية والرومانية؛ لأنه ليس لديهم فناء في الداخل وهم بارتفاع عدة طوابق.

The roadway is unpaved, and full of mud; and there are no sewers.

|道路||未铺砌|||||||||下水道

|road surface||not paved|||||||||drainage systems

|||грунтовий|||||||||каналізаційні

الطريق غير معبد ومليء بالطين. ولا توجد مجاري.

If you walk the streets after nightfall, you must carry a torch to light your footsteps, for there are no street-lamps.

||||||夜幕降临|||||||||||||||

||||||nighttime|||||flashlight or lantern||||||||||

إذا كنت تسير في الشوارع بعد حلول الظلام، فيجب عليك أن تحمل شعلة لإضاءة خطواتك، لأنه لا توجد مصابيح في الشوارع.

There are no policemen; but if you are out after dark, you must beware the "city watch," who take turns in guarding the city, for they will make you give a strict account of yourself.

||||||||||||||||城卫||巡逻|||||||||||给|||||

|||||||||||||be cautious||||||||||||||||||strict|||

لا يوجد رجال شرطة. ولكن إذا خرجت بعد حلول الظلام، فيجب عليك الحذر من "حرس المدينة"، الذين يتناوبون في حراسة المدينة، لأنهم سيجعلونك تقدم حسابًا صارمًا لنفسك.

Now, however, it is day, and we need have no fear.

||||白天|||需要|||

ومع ذلك، فقد حان اليوم، ولا داعي للخوف.

Presently we come into the business parts of the city, and there we find the different trades grouped together in different streets.

||||||||||||||||trades|clustered together||||

نأتي حاليًا إلى الأجزاء التجارية من المدينة، وهناك نجد الحرف المختلفة مجمعة معًا في شوارع مختلفة.

Presently we come into the business parts of the city, and there we find the different trades grouped together in different streets.

Here are the goldsmiths, and there are the tanners; here the cloth merchants, and there the butchers; here the armor-smiths, and there the money-changers.

||||||||制革匠||||||||屠夫们||||金匠||||钱币兑换商|兑换商

|||gold workers|||||tanners||||||||meat sellers|||||||||money-changers

||||||||皮なめし職人|||||||||||||||||

|||золотарі|||||кравці|||||||||||||||||міняльники гро

هنا الصاغة وهناك الدباغون. هنا تجار القماش وهناك الجزارين. هنا الحدادون، وهناك الصيارفة.

The little shops are all on the ground floor, with their wares exposed for sale in the open windows.

|||||||||||goods|displayed||||||

|||||||||||товари|||||||

تقع جميع المتاجر الصغيرة في الطابق الأرضي، وتُعرض بضائعها للبيع في النوافذ المفتوحة.

Let us look in at one of the goldsmiths' shops.

||看一下|||||||

The shop-keeper and his wife are busily engaged waiting on customers and inviting passers-by to stop and examine their goods.

||店主||||||||||||路人|||||||

|||||||||||||beckoning|people walking by|||||inspect||

وصاحب المتجر وزوجته منشغلان بانتظار الزبائن ودعوة المارة للتوقف وتفقد بضائعهم.

Within we see several men and boys at work, making the goods which their master sells.

|||||||||||||||sells

في الداخل نرى العديد من الرجال والفتيان يعملون، ويصنعون البضائع التي يبيعها سيدهم.

There the gold is melted and refined; the right amount of alloy is mixed with it; then it is cast, beaten, and filed into the proper shape.

|||||||||||合金||||||||铸造|||锉磨||||

||||liquefied||purified|||||metal mixture||||||||molded|||shaped|||correct|

|||||||||||||||||||鋳造|||||||

||||||очищений|||||сплав|||||||||||||||

هناك يتم صهر الذهب وتنقيته؛ ويتم خلط كمية مناسبة من السبائك معه؛ ثم يتم صبها وضربها وحفظها بالشكل المناسب.

Then perhaps the article is enameled and jewels are set in it.

|||||上釉||||||

|||||coated with enamel||gems||||

|||стаття||емальований||||||

فربما يكون المقال مطلياً والجواهر مرصعة فيه.

All of these things are done in this one little shop; and so it is for each trade.

||||||||||||因此|||||

كل هذه الأشياء تتم في هذا المتجر الصغير. وهكذا هو الحال في كل تجارة.

The workmen must all begin at the beginning, and start with the rough material; and the "apprentices," as the boys are called, must learn each of the processes by which the raw material is turned into the finished article.

||必须|所有人|开始|||||||||||||||||||学习|||||||||||||||

|workers|||||||||||||||trainees|||||||||||||||||is|||||

||||||||||||||||учні||||||||||||||||||||||виробом

يجب أن يبدأ جميع العمال من البداية، وأن يبدأوا بالمادة الخام؛ ويجب على "المتدربين"، كما يطلق على الأولاد، أن يتعلموا كل عملية من العمليات التي يتم من خلالها تحويل المادة الخام إلى المادة النهائية.

Thus a long term of apprenticeship is necessary for each trade, lasting sometimes for ten years.

|||||apprenticeship|||||profession|||||

ومن ثم فإن التدريب المهني طويل الأمد ضروري لكل حرفة، وقد يستمر أحيانًا لمدة عشر سنوات.

During this time the boys are fed, clothed and lodged with their master's family above the shop, and receive no pay.

|||||||||住宿|||||||||接受||

|||||||||housed|||||||store||||

|||||||||проживають|||||||||||

خلال هذا الوقت يتم إطعام الأولاد وإلباسهم وإقامتهم مع عائلة سيدهم فوق المتجر، ولا يتلقون أي أجر.

If they misbehave, he has the right to punish them; and if they run away, he can pursue them and bring them back.

||不乖||||||||||||||||||带回||

||misbehave||||||||||||||||||||

||погано поводяться||||||||||||||||||||

وإذا أساءوا التصرف، فله الحق في معاقبتهم؛ وإذا هربوا، يمكنه ملاحقتهم وإعادتهم.

Their life, however, is not so hard as that of the peasant boys; and through it all they look forward to the time when their apprenticeship shall be completed.

|||||那么|||||||||||||||||||||||

لكن حياتهم ليست صعبة مثل حياة الأولاد الفلاحين؛ ومن خلال ذلك يتطلعون جميعًا إلى الوقت الذي سيكتمل فيه تدريبهم المهني.

Then they will become full members of the "guild" of their trade, and may work for whatever master they please.

||||||||trade association||||||||any master they choose|||

||||||||цех|||||||||||

وبعد ذلك سوف يصبحون أعضاء كاملي العضوية في "نقابة" تجارتهم، ويمكنهم العمل لدى أي معلم يريدونه.

For a while they may wander from city to city, working now for this master and now for that.

|||||||||||现在|||||现在||

قد يتجولون لفترة من الوقت من مدينة إلى أخرى، ويعملون الآن لهذا السيد، وتارة من أجل ذلك.

In each city they will find the workers at their trade all united together into a guild, with a charter from the king or other lord which permits them to make rules for carrying on of that business and to shut out all persons from it who have not served a regular apprenticeship.

|||||||||||||||||||章程||||||||||||||||的||||||||||||拥有|||||

||||||||||||||||association|||document, agreement, license||||||||allows them|||||||||||||||||||||||||training program

|||||||||||||||||||статут|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

في كل مدينة، سيجدون العمال في تجارتهم متحدين معًا في نقابة، مع ميثاق من الملك أو أي سيد آخر يسمح لهم بوضع قواعد لممارسة هذا العمل وإبعاد جميع الأشخاص عنه الذين لم يفعلوا ذلك. خدم التلمذة الصناعية العادية.

In each city they will find the workers at their trade all united together into a guild, with a charter from the king or other lord which permits them to make rules for carrying on of that business and to shut out all persons from it who have not served a regular apprenticeship.

But the more ambitious boys will not be content with a mere workman's life.

||||||||||||工人的|

||||||||satisfied with|||mere|laborer's|

لكن الأولاد الأكثر طموحًا لن يكتفوا بحياة العمال فقط.

They will look forward still further to a time when they shall have saved up money enough to start in business for themselves.

||期待||||||||||拥有||||||开始||||

وسوف يتطلعون أيضًا إلى الوقت الذي يكونون فيه قد وفروا ما يكفي من المال لبدء العمل التجاري لأنفسهم.

Then they too will become masters, with workmen and apprentices under them; and perhaps, in course of time, if they grow in wealth and wisdom, they may be elected rulers over the city.

||also||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

عندئذ يصبحون هم أيضًا سادة، وتحتهم العمال والمتدربين؛ وربما، مع مرور الوقت، إذا نمت الثروة والحكمة، يمكن انتخابهم حكامًا على المدينة.

So we find the apprentices of the different trades working and dreaming.

ولذلك نجد تلاميذ المهن المختلفة يعملون ويحلمون.

We leave them to their dreams and pass on.

نتركهم لأحلامهم ونمضي.

As we wander about we find many churches and chapels; and perhaps we come after a while to a great "cathedral" or bishop's church, rearing its lofty roof to the sky.

|||||||||小教堂||||来到|||||||||主教的||||||||

|||||||||small churches|||||||||||||belonging to the bishop||rising||tall, elevated||||

||||||||||||||||||||||||そびえ立つ||||||

||||||||||||||||||||||єпископа||||||||

أثناء تجولنا نجد العديد من الكنائس والمصليات. وربما نأتي بعد فترة إلى "كاتدرائية" عظيمة أو كنيسة أسقفية ترتفع سقفها الشامخ إلى السماء.

当我们漫步时,我们发现许多教堂和礼拜堂;或许过了一段时间,我们来到了一个宏伟的“教堂”或主教教堂,耸立的屋顶直入云霄。

No pains have been spared to make this as grand and imposing as possible; and we gaze upon its great height with awe, and wonder at the marvelously quaint and clever patterns in which the stone is carved.

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||奇妙地||||||||||

||||saved|||||large, impressive|||||||look||||||awe|||||extraordinarily clever|charmingly unusual|||designs or motifs||||||sculpted or shaped

||||не пошкодували||||||||||||||||||захоплення|||||чудернаць||||||||||виконано різ

ولم ندخر أي جهد لجعل هذا الأمر عظيمًا ومهيبًا قدر الإمكان؛ ونحن ننظر إلى ارتفاعه الكبير برهبة، ونتعجب من الأنماط الرائعة والغريبة التي تم نحت الحجر بها.

No pains have been spared to make this as grand and imposing as possible; and we gaze upon its great height with awe, and wonder at the marvelously quaint and clever patterns in which the stone is carved.

为了使这个建筑尽可能宏伟和震撼,毫不吝惜任何努力;我们怀着敬畏的心情注视着它的高大,同时对石雕上奇妙而巧妙的图案感到惊奇。

We leave this also after a time; and then we come to the "belfrey" or town-hall.

|||||||||||||钟楼|||

|||||||||||||belfry|||

|||||||||||||鐘楼|||

|||||||||||||дзвіниця|||

ونترك هذا أيضًا بعد حين؛ وبعد ذلك نأتي إلى "برج الجرس" أو دار البلدية.

经过一段时间,我们也离开了这里;然后我们来到“钟楼”或市政厅。

This is the real center of the life of the city.

هذا هو المركز الحقيقي لحياة المدينة.

Here is the strong square tower, like the "donjon" of a castle, where the townsmen may make their last stand in case an enemy succeeds in entering their walls, and they cannot beat him back in their narrow streets.

|||||塔楼|||||||||||||||||||成功||||||||||||||

||||||||||||||||||||||||enters successfully||||||||||||||

||||||||донжон||||||||||||||||вдасться||||||||||||||

هنا هو البرج المربع القوي، مثل "دونجون" القلعة، حيث يمكن لسكان المدينة أن يتخذوا موقفهم الأخير في حالة نجاح العدو في دخول أسوارهم، ولم يتمكنوا من هزيمته في شوارعهم الضيقة.

On top of the tower is the bell, with watchmen always on the lookout to give the signal in case of fire or danger.

|||||||||守望者||||||发出||||||||

|||||||||guards||||watchfulness||||||||||

|||||||||сторожі||||||||||||||

يوجد الجرس أعلى البرج، حيث يراقب الحراس دائمًا لإعطاء الإشارة في حالة نشوب حريق أو خطر.

The bell is also used for more peaceful purposes, as it gives the signal each morning and evening for the workmen all over the city to begin and to quit work; and it also summons the citizens from time to time, to public meetings.

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||工作|||||||||||||

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||stop|||||calls together|||||||||

يُستخدم الجرس أيضًا لأغراض أكثر سلمية، فهو يعطي الإشارة كل صباح ومساء للعمال في جميع أنحاء المدينة لبدء العمل والتوقف عنه؛ كما يدعو المواطنين من وقت لآخر إلى الاجتماعات العامة.

The bell is also used for more peaceful purposes, as it gives the signal each morning and evening for the workmen all over the city to begin and to quit work; and it also summons the citizens from time to time, to public meetings.

Within the tower are dungeons for prisoners, and meeting rooms for the rulers of the city.

||||dungeons|||||||||||

ويوجد داخل البرج زنزانات للسجناء، وقاعات اجتماعات لحكام المدينة.

There also are strong rooms where the city money is kept, together with the city seal.

|||安全的||||||||||||

|||||||||||||||official emblem

هناك أيضًا غرف قوية يتم فيها حفظ أموال المدينة مع ختم المدينة.

Lastly there is the charter which gives the city its liberties; this is the most precious of all the city possessions.

finally||||charter||grants to||||freedoms||||||||||assets

Останнє||||||||||||||||||||

وأخيرًا، هناك الميثاق الذي يمنح المدينة حرياتها؛ هذا هو أثمن ممتلكات المدينة.

Even in ordinary times the city presents a bustling, busy appearance.

||||||shows||lively and busy||

||||||||жвава||

حتى في الأوقات العادية تقدم المدينة مظهرًا صاخبًا ومزدحمًا.

If it is a city which holds a fair once or twice a year, what shall we say of it then?

||||||||||||||那么我们该说什么|||说|关于它||

||||||||fair event||||||||||||

فإذا كانت مدينة تقام فيها المعارض مرة أو مرتين في السنة فماذا نقول عنها إذن؟

For several weeks at such times the city is one vast store.

||||||||||immense expanse|

ولعدة أسابيع في مثل هذه الأوقات، تظل المدينة متجرًا كبيرًا.

Strange merchants come from all parts of the land and set up their booths and stalls along the streets, and the city shops are crowded with goods.

|||||||||||||booths||booths, market stands|throughout||||||||||

|||||||||||||屋台|||||||||||||

ويأتي التجار الغرباء من كل أصقاع الأرض ويقيمون أكشاكهم وأكشاكهم على طول الشوارع، وتزدحم دكاكين المدينة بالبضائع.

Strange merchants come from all parts of the land and set up their booths and stalls along the streets, and the city shops are crowded with goods.

For miles about the people throng in to buy the things they need.

|||||涌入|||||||

|||||crowd|||||||

|||||群衆|||||||

لأميال حول الناس المحتشدين لشراء الأشياء التي يحتاجون إليها.

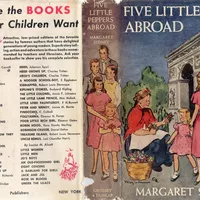

Take a look at the picture of the streets of a city during fair-time in the thirteenth century.

ألقِ نظرة على صورة شوارع إحدى المدن خلال فترة المعرض في القرن الثالث عشر.

In the middle of the picture we see a townsman and his wife returning home after making their purchases.

|||||||||镇民|||||||||

|||||||||local resident|||||||||purchases

|||||||||мешканець мі|||||||||

في منتصف الصورة نرى أحد سكان المدينة وزوجته يعودان إلى المنزل بعد إجراء مشترياتهما.

Behind them are a knight and his attendant, on horseback, picking their way through the crowd.

|||||||随从|||小心行走|||||

|||||||servant|||picking|||||

وخلفهم يوجد فارس ومرافقه، على ظهور الخيل، يشقان طريقهما بين الحشد.

On the right hand side of the street is the shop of a cloth merchant; and we see the merchant and his wife showing goods to customers, while workmen are unpacking a box in the street.

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||拆包|||||

|||||||||||||fabric|trader||||||||||||||||unpacking|||||

على الجانب الأيمن من الشارع يوجد محل تاجر أقمشة. ونرى التاجر وزوجته يعرضان البضائع على الزبائن، بينما يقوم العمال بتفريغ صندوق في الشارع.

Next door is a tavern, with its sign hung out; and near this we see a cross which some pious person has erected at the street corner.

|||||||||||||||||||devout|||set up||||

في البيت المجاور توجد حانة معلقة عليها لافتة؛ وبالقرب من هذا نرى صليبًا أقامه أحد الأشخاص التقيين في زاوية الشارع.

On the left-hand side of the street we see a cripple begging for alms.

|||||||||||残疾人|乞讨||

|||||||||||disabled person|requesting charity||charity donations

||||||||||||||施し

|||||||||||інвалід|||

على الجانب الأيسر من الشارع نرى مقعدًا يتسول الصدقات.

Back of him is another cloth-merchant's shop; and next to this is a money-changer's table, where a group of people are having money weighed to see that there is no cheating in the payment.

后面||||||商人的||||||||钱|换钱商||||||||||||||||||||

||||||merchant|||||||||money changer's||||||||||measured||||||||||

|||||||||||||||міняльника||||||||||||||||||||

خلفه محل آخر لتاجر الأقمشة. وبجانب ذلك طاولة الصراف، حيث يقوم مجموعة من الأشخاص بوزن الأموال للتأكد من عدم وجود غش في الدفع.

Beyond this is an elevated stage, on which a company of tumblers and jugglers are performing, with a crowd of people about them.

||||||||一个|||杂技演员||杂技演员||||一个|||||

||||raised platform|platform||||||acrobats||performers|||||||||

|||||||||||акробати|||||||||||

وخلف ذلك يوجد مسرح مرتفع، حيث تؤدي مجموعة من البهلوانات والمشعوذين، مع حشد من الناس حولهم.

In the background we see some tall-roofed houses, topped with turrets, and beyond these we can just make out the spire of a church rising to the sky.

||||||||||||||||||看出||||||||||

|||||||||adorned with||small towers||||||||||steeple|||||||

|||||||||||||||||||||вежа|||||||

في الخلفية نرى بعض المنازل ذات الأسطح العالية، التي تعلوها الأبراج، ومن خلفها يمكننا فقط رؤية برج الكنيسة يرتفع إلى السماء.

This is indeed a busy scene; and it is a picture which we may carry away with us.

هذا بالفعل مشهد مزدحم. وهي الصورة التي قد نحملها معنا.

This is indeed a busy scene; and it is a picture which we may carry away with us.

It well shows the energy and the activity which, during the later Middle Ages, made the towns the starting place for so many important movements.

||显示|||||||||||||||the|||||||

إنه يُظهر جيدًا الطاقة والنشاط اللذين جعلا المدن، خلال أواخر العصور الوسطى، نقطة انطلاق للعديد من الحركات المهمة.