Chapter IX.

When Charles arose in the morning, he found there had been a pleasant spring shower, which had beautified every thing on the island. There was a sweet smell from the herbage, a refreshing air fanned the budding trees, and the little birds were twittering on every bough. Charles felt the sweet influence of the season, and his heart ascended in praise to the bountiful Giver of all good: he then went to the stream, and finding some fish in his net, he proceeded to make a fire, and procure the meal he so much required. Whilst it was roasting, he opened the Bible, and began to read the Proverbs of Solomon, which he did not recollect reading before, as the historical parts of the Old Testament had naturally engaged his attention the most. He had not read far, when he found the words, "Hope deferred maketh the heart sick; but when the desire cometh, it is a tree of life." "Ah!" cried Charles, "I had a sad fit of that very sickness last night, and the effects are not gone off yet. It was not only very foolish in me to give way to my sense of sorrow so much, but very ungrateful also, for within a very short time I have been so mercifully delivered from many dangers, that I am sure I might sing that hymn which says— 'I'll praise thee, I'll praise thee, for all that's past, And trust thee for all that is to come.' Instead of which, the very first disappointment I had, completely unmanned me. I find I am only a child yet, though I am almost fourteen years old; and have had experience enough in the last six months, to give me a push in life." In consequence of these reflections, Charles came to a resolution, which it was very difficult to keep; he determined to carry a design of preparing for his return into execution, and at the same time, allowing himself only to watch three hours a-day; and at other times to keep himself as busy as if he were going to live on the island all his life. He thought that by watching at three different periods of the day, he should insure every advantage likely to occur, since, in so wide an horizon, the progress of any vessel might be traced many hours; and he was aware, from past experience, that the agitation he experienced when a ship was actually within sight, was such, that it took away the very strength which he would so greatly need, if any actual chance for escape presented itself.

The preparations for departure (on which he had set his heart) consisted of making a considerable selection of those beautiful sea-shells on the other side of the island, which we formerly mentioned, as a present for his sister Emily, and of keeping his boat clean, and in order for going out at a moment's warning, with a little stock of provisions. For this purpose, every morning at rising, he sought the shells, which in the evening he arranged; and to these he added a considerable stock of beautiful feathers, which he had gathered, and put into a corner of the hut; the shells he laid carefully in layers, at the bottom of the box, between the folds of the muslin; the feathers he stuck in lines upon his writing-paper, disposing them in different shades and forms, so as to make very pretty pictures; and in several he made the letter E, in green and scarlet feathers, upon a ground of dark brown, or brilliant white. This employment was so pleasant to him, that he regretted much that he had not begun it sooner, for many a lonely hour was beguiled by an amusement which exercised his taste, as well as his affections; and often would he look at the last piece he had finished, and think of the pleasure it would give his sister, without that too-natural conclusion that her eyes, in all probability, would never behold it.

Whenever Charles went to the shore, he took his gun with him, and now frequently, either with that or his bow and arrow, shot a rabbit, as the weather was become warm, and the creatures were again seen frisking in his path. He noticed in his walks also, abundance of a plant, which, on plucking up, had a root resembling a small carrot, and undoubtedly was a wild species, which eat very well, and he soon found to be very nutritious. He took it very sparingly at first, but on finding no bad effects from eating it, got it freely; and having boiled it in his tea-kettle, found it an excellent substitute for bread; and he even contrived, by crushing it into cakes, and drying it in the sun, to make it a substitute for the biscuits which he had finished. As soon as he had contrived to dry a few of these cakes very thoroughly, he put them by as a store into his boat, for which also he provided some slips of dried fish. Often did he wish for salt, thinking, that if he possessed the power of curing some fish, he might have ventured on a long voyage, for the sea was now so calm, and the weather so settled, that he again earnestly desired to set out; but he no longer wished to visit the neighbouring island, which, he was persuaded, was a much worse place than his present abode, and equally uninhabited.

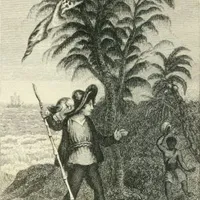

At length, one morning, with feelings of unspeakable delight, Charles again distinctly perceived a ship, tracing her progress over the liquid plain, in a much nearer direction than the last had done, as for some time he thought her bearing for Amsterdam. As he carried one of the shawls about his person, he lost not a moment in taking it, and streaming it out in the wind, by tying it to the highest part of the tree. He then descended, flew to the hut, took out all that he could carry, regretting exceedingly, that after all his pains, the box with the sea-shells must be left behind, and hastened down to his boat. It required great exertion at this moment to get out to sea, but the energies awakened by his present excitement conquered every obstacle; in a few minutes he had pushed into the sea, spread his sail, rejoiced in a rising breeze, and felt convinced that he should shortly attract the attention of some person on the deck of the ship, which was seldom a single moment out of his sight; for such was his dread of losing this precious object, that he had scarcely the power of attending to his own vessel.

In about half an hour he had the additional satisfaction of perceiving that one of her boats was out fishing, and therefore he had the greater reason to hope that he should be seen: in a little time he fired, and continued to do so at intervals, for more than an hour; but as no notice whatever was taken, he concluded either that he remained unheard and unseen, or else that the crew were persons of great inhumanity. When this idea struck him, he became extremely anxious on the subject of Captain Gordon's property, thinking that if he fell into bad hands, it was but too probable that he should be stripped and murdered, for the sake of securing it to the plunderers; and for a moment he conceived that the best thing he could do, would be to throw it into the sea. This however he would not do, till there appeared a positive necessity for it, as it was (next to seeing his parents again) the first wish of his heart to restore this fortune to the innocent orphans, who, perhaps, at this very moment were in want of it; and he even hoped, that in case he should be taken as a prisoner, rather than a friend, he might find the means of secreting it, since he wore it nearest his body, well secured by the best bandages it had been in his power to make.

Just as Charles had made this conclusion, he perceived the boat quit its late position, and he again fired. Alas! its motion was towards the ship; what would he not have given for more sails—for the power of making a louder report—for any means whereby to reach the senses, and touch the hearts of his fellow-creatures! "Oh that I had wings like a dove!" was on his lips, as, with outstretched hands and streaming eyes, he gazed towards the ship, which every moment receded more swiftly from his sight, and in another hour, left him alone in the wide ocean, out of the sight of every human eye, and far from all human help, every moment leaving still farther the desolate island, which he yet held to be his home.

"What a foolish boy I am to cry again!" ejaculated Charles, at length; "I may have a dozen failures, and yet be taken up at last; besides, that very ship may be going to China, for any thing I know; and in that case, I should be taken much further from my native land than I am here; and if my poor father should come to seek me, I should be completely lost." At the name of his father, his heart sunk; it was now nineteen weeks complete since he had so mysteriously disappeared from the island; and it seemed hardly likely, that in that time no means should have arisen for conveying intelligence. On the other hand, unless his father had the positive command of a vessel, how could he come or send for him, since it was too plain that no vessels were in the habit of touching either here or at Amsterdam? There had been no severe weather, likely to have proved an hindrance, for the last three months; but this might make no difference to Mr. Crusoe, for as he had gone from hence poor and shipwrecked, he, who once could command so much, might now be able to procure not even a paltry sloop, with which to rescue his only son.

Poor Charles was compelled to abandon this course of distressing reflections, to think of his own safety, and change the direction of his little vessel. For many hours he was obliged to tack, with little success; and although he was not exposed to severe weather as before, he was out a second night, finding it even more difficult than then to affect a landing. When he at length moored his boat, it was in a little bay, much more convenient than he had yet found, and also nearer to the hut: therefore he resolved that for the present it should remain there; and after covering it with branches, he returned, thoughtful, but not dejected, to his hut once more.

The first thing Charles saw, or indeed heard, was poor Poll. The bird had been asleep at the time when he set out, and in his hurry, for the first time, he had actually forgotten him; and such was the agitation of his spirits for the first hour or two, that even this, his dear and only companion, failed to be remembered. When, however, he did think of Poll, the recollection of having left him behind, grieved him so much, that it rendered his disappointment less afflictive to him, when he lost sight of the ships; and he determined, that for the future, he would take him on his shoulders wherever he went. He also emptied his box, to enable him to carry it down to the boat, and then carefully, and with much labour, replaced the contents, thus rendering himself ready to go at any moment; but being also aware, that he might yet be compelled to remain an indefinite time, he made himself a seat in the hut, by heaping up sand, and covering it with the skins of the animals he had killed, after sewing them together with the fibres of leaves.

There were times when he wished much to lay out a little garden, as he had now discovered several other vegetables, besides the carrots, which he thought would answer for food; but his want of a spade forbade his progress in preparing the ground; for although the shovel, which was his only instrument, managed to remove sand, it was quite inadequate to digging the earth. It was a great pleasure to see all the fruits promised to be abundant, and to remember that the season for finding dates, in particular, was coming on; for such was his dislike to killing any living thing, that nothing but positive necessity could induce him to shed blood; and he thought, that if he were compelled to remain another year, he would manage to do without any animal food, except turtle, which he flattered himself he could kill easily, and which he had found to be particularly nutritive food.

Again and again, he went to his usual points; but though he sometimes fancied he saw vessels in the extreme distance, yet day after day passed, and no more vessels came, as before, within his actual observation; and he almost repented, that when he was so far out, he had returned to the island; and as to his hopes of his father's arrival, they became every day more faint; so that he ceased to count the days upon his almanack, because they diminished hopes, which, from the first, had rather sprung from his affections than his reason. At this time, he planted many little shrubs around the grave of Captain Gordon, and inscribed his name in the bark of the trees near it, not unfrequently cutting his own likewise. His mind was in such a state of inquietude, that he could not read at all; but every active pursuit was of benefit to him; and often, while he wept his father's loss, would he recal his words, and with true wisdom and warm affection, resolved, as far as he could, to follow his advice in all things. Then would he rouse himself to action, by running to look at his boat, gathering sticks for his fire, or adding to his stock of shells, by which means he would attain sufficient composure to read, and think on the subject before him, and finally, to pray devoutly, and sleep comfortably.