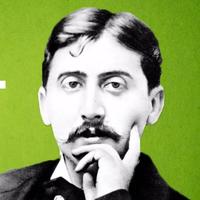

Marcel Proust. LITERATURE. Part 2/2.

||EDEBİYAT|

Marcel Proust. LITERATUR. Teil 2/2.

Marcel Proust. LITERATURA. Parte 2/2.

Marcel Proust. LITTÉRATURE. Partie 2/2.

Marcel Proust. LETTERATURA. Parte 2/2.

マルセル・プルーストLITERATUREパート2/2

마르셀 프루스트. 문학. 파트 2/2.

Marcel Proust. LITERATUUR. Deel 2/2.

Marcel Proust. LITERATURA. Część 2/2.

Marcel Proust. LITERATURA. Parte 2/2.

Марсель Пруст. ЛИТЕРАТУРА. Часть 2/2.

Marcel Proust. EDEBİYAT. Bölüm 2/2.

Марсель Пруст. ЛІТЕРАТУРА. Частина 2/2.

马塞尔·普鲁斯特。文学。第 2/2 部分。

馬塞爾·普魯斯特。文學。第 2/2 部分。

This brings us to the third and only successful candidate for the meaning of life: ART.

|もたらす||||||||候補者||||||

Damit sind wir bei dem dritten und einzigen erfolgreichen Kandidaten für den Sinn des Lebens: KUNST.

Cela nous amène au troisième et unique candidat au sens de la vie : L'ART.

For Proust, the great artists deserve acclaim because they show us the world in a way that is fresh, appreciative, and alive.

|||||受ける|称賛|||||||||||||感謝する||

||||||beröm|||||||||||||||

Für Proust verdienen die großen Künstler Anerkennung, weil sie uns die Welt auf eine frische, wertschätzende und lebendige Weise zeigen.

Now the opposite of art for Proust is something he calls habit.

||反対|||||||||

Das Gegenteil von Kunst ist für Proust nun etwas, das er Gewohnheit nennt.

For Proust, much of life is ruined for us by a blanket or shroud of familiarity that descends between us and everything that matters.

|||||||||||||遮蔽||||||||||

||||||台無し|||||毛布||覆い||親しみ||降りかかる||||||大切な

|||||||||||||slöja||||sänker sig||||||

Für Proust wird ein Großteil des Lebens durch eine Decke oder einen Mantel der Vertrautheit ruiniert, der sich zwischen uns und alles, was wichtig ist, legt.

Pour Proust, une grande partie de la vie est gâchée par une couverture ou un linceul de familiarité qui s'interpose entre nous et tout ce qui compte.

Habits dull our senses and stops us appreciating everything, from the beauty of a sunset to our work and our friends.

|鈍くする||感覚||||感謝する|||||||夕日||||||

Gewohnheiten stumpfen unsere Sinne ab und hindern uns daran, alles zu schätzen, von der Schönheit eines Sonnenuntergangs bis zu unserer Arbeit und unseren Freunden.

Children don’t suffer from habit, which is why they get excited by some very key but simple things like puddles, jumping on the bed, sand and fresh bread.

||苦しむ||||||||興奮する|||||||||水たまり|||||砂||新しい|

|||||||||||||||||||pölar||||||||

Kinder haben keine Gewohnheit, und deshalb begeistern sie sich für so wichtige, aber einfache Dinge wie Pfützen, das Springen auf dem Bett, Sand und frisches Brot.

Les enfants ne souffrent pas de l'habitude, c'est pourquoi ils sont excités par des choses essentielles mais simples comme les flaques d'eau, les sauts sur le lit, le sable et le pain frais.

But we adults get spoilt about everything; which is why we seek ever more powerful stimulants like the aforementioned fame and love.

||||甘やかされ|||||||求める||||刺激物|||前述の|名声||

||||||||||||||||||den nämnda|||

Aber wir Erwachsenen werden von allem verwöhnt; deshalb suchen wir nach immer stärkeren Stimulanzien wie dem bereits erwähnten Ruhm und der Liebe.

Mais nous, les adultes, nous sommes gâtés pour tout ; c'est pourquoi nous recherchons des stimulants toujours plus puissants, comme la célébrité et l'amour.

The trick – in Proust’s eyes – is to recover the powers of appreciation of a child in adulthood, to strip the veil of habit and therefore to start to appreciate (to look upon) daily life with a new (and more grateful) sensitivity.

|技||||||取り戻す||||感謝|||||大人の時期||剥がす||ヴェール||||したがって||||評価する|||||||||||感謝する|感受性

Die Kunst besteht in Prousts Augen darin, als Erwachsener die Wahrnehmungsfähigkeit eines Kindes wiederzuerlangen, den Schleier der Gewohnheit abzulegen und so das tägliche Leben mit einer neuen (und dankbareren) Sensibilität zu schätzen (zu betrachten).

L'astuce - aux yeux de Proust - consiste à retrouver les capacités d'appréciation d'un enfant à l'âge adulte, à ôter le voile de l'habitude et donc à commencer à apprécier (à regarder) la vie quotidienne avec une sensibilité nouvelle (et plus reconnaissante).

This for Proust is what one group in the population does all the time: artists.

|||||||||人口|||||

Pour Proust, c'est ce que fait en permanence un groupe de la population : les artistes.

Artists are people who know how strip habit away and return life to its true deserved glory, for example, when they show us water lilies or service stations, or buildings in a new light.

||||||ta bort||||||||||||||||||vattenspeglar|||||||||

||||||strip(1)|||||||||真の価値|栄光||||||||睡蓮|||||||||

Künstler sind Menschen, die es verstehen, Gewohnheiten abzustreifen und dem Leben seine wahre, verdiente Pracht zurückzugeben, wenn sie uns beispielsweise Seerosen, Tankstellen oder Gebäude in einem neuen Licht zeigen.

Les artistes sont des personnes qui savent dépouiller l'habit et rendre à la vie sa vraie gloire méritée, par exemple lorsqu'ils nous montrent des nénuphars ou des stations-service, ou des bâtiments sous un nouveau jour.

Proust’s goal isn’t that we should necessarily make art or be someone who hangs out in museums all the time.

||||||必ずしも||||||||||美術館|||

Prousts Ziel ist es nicht, dass wir unbedingt Kunst machen oder uns ständig in Museen aufhalten sollten.

L'objectif de Proust n'est pas de faire de l'art ou d'être quelqu'un qui passe son temps dans les musées.

The idea is to get us to look at the world, our world, with some of the same generosity as an artist, which would mean taking pleasure in simple things – like water, the sky or a shaft of light on a piece of paper.

||||||||||||||||||寛容さ||||||||喜び||||||||||光線|||||||

Die Idee ist, uns dazu zu bringen, die Welt, unsere Welt, mit der gleichen Großzügigkeit wie ein Künstler zu betrachten, was bedeuten würde, sich an einfachen Dingen zu erfreuen - wie Wasser, dem Himmel oder einem Lichtstrahl auf einem Blatt Papier.

L'idée est de nous amener à regarder le monde, notre monde, avec un peu de la même générosité qu'un artiste, c'est-à-dire en prenant plaisir à des choses simples, comme l'eau, le ciel ou un trait de lumière sur une feuille de papier.

It’s no coincidence that Proust’s favourite painter was Vermeer: a painter who knew how to bring out the charm and the value of the everyday.

||偶然||||画家||フェルメール||||||||||魅力||||||

The spirit of Vermeer hangs over his novel: it too is committed to the project of reconciling us to the ordinary circumstances of life – and some of Proust’s most compelling pieces of writing describe the charm of the everyday: like reading in a train, driving at night, smelling the flowers in spring time and looking at the changing light of the sun on the sea.

|||||||||||コミットしている|||||和解させる||||普通の|状況||||||||魅力的な|作品|||描写する||魅力|||||||||運転する|||匂いを嗅ぐ||||||||||変化する|||||||

||||||||||||||||att förena|||||||||||||fängslande|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Der Geist Vermeers schwebt über seinem Roman: auch er hat sich dem Projekt verschrieben, uns mit den gewöhnlichen Umständen des Lebens zu versöhnen - und einige von Prousts fesselndsten Texten beschreiben den Charme des Alltäglichen: wie das Lesen in einem Zug, das Autofahren bei Nacht, der Geruch der Blumen im Frühling und der Blick auf das wechselnde Licht der Sonne auf dem Meer.

L'esprit de Vermeer plane sur son roman : lui aussi s'est engagé dans le projet de nous réconcilier avec les circonstances ordinaires de la vie - et certains des écrits les plus convaincants de Proust décrivent le charme du quotidien : lire dans un train, conduire la nuit, sentir les fleurs au printemps et regarder la lumière changeante du soleil sur la mer.

Proust is famous for having written about the dainty little cakes the French call ‘madeleines'.

||||||||||||||玛德琳蛋糕

||||||||delikata||||||

||||||||可愛い||ケーキ||||マドレーヌ

Proust est célèbre pour avoir écrit sur les délicats petits gâteaux que les Français appellent "madeleines".

[4]

[4]

The reason has to do with his thesis about art and habit.

|||||||論文||||

Der Grund dafür liegt in seiner These über Kunst und Gewohnheit.

La raison en est sa thèse sur l'art et l'habitude.

Early on in the novel, the narrator tells us that he had been feeling depressed and sad for a while when one day he had a cup of herbal tea and a madeleine – and suddenly the taste carried him powerfully back (in the way that flavours sometimes can) to years in his childhood when as a small boy he spent his summers in his aunt’s house in the French countryside.

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||草本|||||||||||||||||味道||||||||||||||||||||||||

||||||語り手||||||||落ち込んで||悲しい||||||||||||ハーブの||||マドレーヌ||||味|||強く||||||味|||||||子供時代|||||||||夏|||叔母の|||||田舎

Zu Beginn des Romans erzählt der Erzähler, dass er sich seit einiger Zeit deprimiert und traurig fühlte, als er eines Tages eine Tasse Kräutertee und eine Madeleine zu sich nahm - und plötzlich versetzte ihn der Geschmack mit Macht in die Jahre seiner Kindheit zurück, als er als kleiner Junge die Sommer im Haus seiner Tante in der französischen Provinz verbrachte.

Au début du roman, le narrateur nous raconte qu'il se sentait déprimé et triste depuis un certain temps lorsqu'un jour il a bu une tasse de tisane et mangé une madeleine - et soudain le goût l'a ramené puissamment (comme les saveurs peuvent parfois le faire) aux années de son enfance où, petit garçon, il passait ses étés dans la maison de sa tante, dans la campagne française.

A stream of memories comes back to him, and fills him with hope and gratitude.

|流れ||思い出||||||彼を|||||感謝

Ein Strom von Erinnerungen kehrt in ihm zurück und erfüllt ihn mit Hoffnung und Dankbarkeit.

Un flot de souvenirs lui revient et le remplit d'espoir et de gratitude.

Thanks to the madeleine, Proust’s narrator has what has since become known as “A PROUSTIAN MOMENT”: a moment of sudden involuntary and intense remembering, when the past promptly emerges unbidden from a smell, a taste or a texture.

|||マドレーヌ||語り手|||||なった||||プルースト的||||||無意識の||強烈な|記憶|||||現れる|自発的に|||匂い||味|||テクスチャ

||||||||||||||||||||oförmådd|||||||||utan att bjudas in||||||||

Dank der Madeleine erlebt Prousts Erzähler das, was seither als PROUST'scher MOMENT" bekannt geworden ist: einen Moment plötzlicher, unwillkürlicher und intensiver Erinnerung, in dem die Vergangenheit prompt und unaufgefordert aus einem Geruch, einem Geschmack oder einer Textur auftaucht.

Grâce à la madeleine, le narrateur de Proust connaît ce que l'on a appelé depuis "UN MOMENT PROUSTIEN" : un moment de souvenir soudain, involontaire et intense, où le passé surgit promptement et sans crier gare d'une odeur, d'un goût ou d'une texture.

Through its rich evocative power, what the Proustian moment teaches us is that life isn’t necessarily dull and without excitement – it’s just one forgets to look at it in the right way: we forget what being alive, fully alive, actually feels like.

|||framkallande||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|||呼び起こす||||プルースト的||||||||必ずしも|退屈|||興奮||||忘れる||||||||||||||完全に||||

Der Proust'sche Moment lehrt uns durch seine suggestive Kraft, dass das Leben nicht unbedingt langweilig und unaufregend ist - man vergisst nur, es auf die richtige Weise zu betrachten: Wir vergessen, wie es sich anfühlt, lebendig zu sein, voll und ganz lebendig.

Par sa richesse évocatrice, le moment proustien nous apprend que la vie n'est pas nécessairement terne et sans excitation - c'est juste qu'on oublie de la regarder de la bonne manière : on oublie ce que c'est que d'être en vie, pleinement en vie.

The moment with the tea is pivotal in the novel because it demonstrates everything Proust wants to teach us about appreciating life with greater intensity.

||||||重要な||||||示している|||||教える|||感謝する||||強度

Der Moment mit dem Tee ist ein Schlüsselmoment des Romans, denn er zeigt alles, was Proust uns lehren will, das Leben intensiver zu schätzen.

Le moment du thé est essentiel dans le roman car il démontre tout ce que Proust veut nous apprendre sur la manière d'apprécier la vie avec plus d'intensité.

It helps his narrator to realise that it isn’t his life which has been mediocre, so much as the image of it he possessed in normal that is voluntary memory.

|||語り手||気づく|||||||||平凡な|||||||||持っていた|||||自発的な|

|||||||||||||||||||||||hade||||||

Il aide son narrateur à comprendre que ce n'est pas sa vie qui a été médiocre, mais plutôt l'image qu'il en a eue en temps normal et qui est une mémoire volontaire.

Proust writes:

|書く

“The reason why life may be judged to be trivial although at certain moments it seems to us so beautiful is that we form our judgement, ordinarily, not on the evidence of life itself but of those quite different images which preserve nothing of life – and therefore we judge it disparagingly.”

||||||判断される|||些細な||||||||||||||下す|||普通は|||||||||||かなり||画像||保存する|||||したがって||||軽蔑して

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||bevara|||||||||nedlåtande

"Der Grund, warum das Leben als trivial beurteilt werden kann, obwohl es uns in bestimmten Momenten so schön erscheint, liegt darin, dass wir unser Urteil gewöhnlich nicht auf der Grundlage des Lebens selbst bilden, sondern auf der Grundlage ganz anderer Bilder, die nichts vom Leben bewahren - und deshalb urteilen wir abschätzig darüber."

"La raison pour laquelle la vie peut être jugée insignifiante alors qu'à certains moments elle nous semble si belle est que nous formons notre jugement, d'ordinaire, non pas sur la base de la vie elle-même, mais de ces images tout à fait différentes qui ne conservent rien de la vie - et donc nous la jugeons de manière désobligeante".

That’s why artists are so important.

Their works are like long Proustian moments.

|||||プルースト的な|

Leurs œuvres sont comme de longs moments proustiens.

They remind us that life truly is beautiful, fascinating and complex, and thereby they dispel our boredom and our ingratitude.

|思い出させて|||||||魅力的な||複雑な||それによって||払拭する||退屈|||不満

||||||||||||||skingra|||||otacksamhet

Ils nous rappellent que la vie est vraiment belle, fascinante et complexe, et ils dissipent ainsi notre ennui et notre ingratitude.

Proust’s philosophy of art is delivered in a book which is itself exemplary of what he’s saying.

|哲学|||||||||||模範的||||

Prousts Kunstphilosophie wird in einem Buch dargelegt, das selbst beispielhaft ist für das, was er sagt.

La philosophie de l'art de Proust est livrée dans un livre qui est lui-même exemplaire de ce qu'il dit.

It is a work of art that brings the beauty and interest of the world back to life.

|||||||もたらす||||||||||

C'est une œuvre d'art qui redonne vie à la beauté et à l'intérêt du monde.

Reading it, your senses are reawakened, a thousand things you normally forget to notice are brought to your attention, he makes you for a time, as clever and as sensitive as he was – and for this reason alone, we should be sure to read him and the 1.2 million words he assembled for us.

|||感覚||再び目覚める|||||普段|||気づく|||||注意||||||||賢い|||敏感|||||||||||||||||||||再び目覚めさせる||

Bei der Lektüre werden die Sinne neu geweckt, tausend Dinge, die man sonst vergisst, werden einem vor Augen geführt, er macht einen für eine Weile so klug und sensibel, wie er es war - und schon deshalb sollte man ihn und die 1,2 Millionen Worte, die er für uns zusammengetragen hat, unbedingt lesen.

En le lisant, vos sens sont en éveil, mille choses que vous oubliez normalement de remarquer sont portées à votre attention, il vous rend, pour un temps, aussi intelligent et sensible qu'il l'était - et pour cette seule raison, nous devrions être sûrs de le lire, lui et les 1,2 million de mots qu'il a rassemblés pour nous.

And thereby, learn to appreciate existence before it is too late.

|それによって|||感謝する|存在|||||