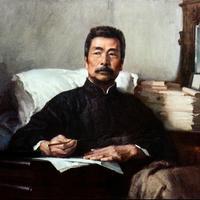

#41:鲁迅 和 他 笔下 的 人

Lu Xun|and|his|pen|attributive marker|characters

#Nr. 41: Lu Xun und die Menschen, über die er geschrieben hat

#41: Ο Lu Xun και οι άνθρωποι για τους οποίους έγραψε

#41: Lu Xun y la gente sobre la que escribió

#41 : Lu Xun et les personnes sur lesquelles il a écrit

#41: Lu Xun e le persone di cui scriveva

#41: Lu Xun e as pessoas sobre quem escreveu

#41: Lỗ Tấn và những nhân vật trong tác phẩm của ông

#41: 魯迅と彼の筆の下の人々

#41: Lu Xun and the Characters He Created

英国 的 读者 GavinBanks 让 我 介绍 中国 文学 ,我 首先 想到 的 就 是 鲁迅 。

UK|attributive marker|reader|Gavin Banks|let|I|introduce|China|literature|I|first|think of|attributive marker|just|is|Lu Xun

Der britische Leser GavinBanks bat mich, chinesische Literatur vorzustellen. Das erste, woran ich dachte, war Lu Xun.

Gavin Banks, un lector del Reino Unido, me pidió que presentara la literatura china y lo primero en lo que pensé fue en Lu Xun.

Lorsque Gavin Banks, un lecteur du Royaume-Uni, m'a demandé de présenter la littérature chinoise, la première chose qui m'est venue à l'esprit a été Lu Xun.

Il lettore britannico GavinBanks mi ha fatto conoscere la letteratura cinese, e il primo a cui ho pensato è stato Lu Xun.

Gavin Banks, um leitor do Reino Unido, pediu-me que apresentasse a literatura chinesa e a primeira coisa em que pensei foi em Lu Xun.

Читач із Великої Британії Гевін Бенкс попросив мене познайомити з китайською літературою, і першою людиною, про яку я згадаю, є Лу Сюн.

Người đọc người Anh Gavin Banks đã khiến tôi giới thiệu về văn học Trung Quốc, tôi đầu tiên nghĩ đến Lỗ Tấn.

イギリスの読者ギャビン・バンクスが私に中国文学を紹介させてくれたので、まず思い浮かんだのは魯迅です。

A British reader, Gavin Banks, asked me to introduce Chinese literature, and the first person that came to my mind was Lu Xun.

很多 年 来 ,鲁迅 的 作品 一直 出现 在 中国 学生 的 教科书 上 。

many|years|since|Lu Xun|attributive marker|works|always|appear|in|China|students|attributive marker|textbooks|on

Seit vielen Jahren erscheinen Lu Xuns Werke in Lehrbüchern chinesischer Studenten.

Durante muchos años, las obras de Lu Xun han aparecido en los libros de texto de los estudiantes chinos.

Depuis de nombreuses années, les œuvres de Lu Xun figurent dans les manuels scolaires des étudiants chinois.

Da molti anni, le opere di Lu Xun compaiono nei libri di testo degli studenti cinesi.

Протягом багатьох років твори Лу Сюня постійно з'являються в підручниках для китайських студентів.

Trong nhiều năm qua, tác phẩm của Lỗ Tấn luôn xuất hiện trong sách giáo khoa của sinh viên Trung Quốc.

何年もの間、魯迅の作品は中国の学生の教科書に常に掲載されています。

For many years, Lu Xun's works have appeared in the textbooks of Chinese students.

鲁迅 在 中国 几乎 无人 不 知 、无人 不 晓 。

Lu Xun|in|China|almost|no one|not|know|no one|not|understand

Lu Xun ist in China so gut wie jedem bekannt.

Lu Xun es conocido por casi todo el mundo en China.

Lu Xun est connu de presque tous les Chinois.

Lu Xun è praticamente conosciuto da tutti in Cina.

Lu Xun é conhecido por quase toda a gente na China.

Лу Сюн у Китаї майже ніким не забутий і його твори відомі всім.

魯迅は中国ではほとんど誰もが知っている存在です。

Lu Xun is known by almost everyone in China.

鲁迅 的 真名 叫 周树人 ,鲁迅 是 他 的 笔名 。

Lu Xun|attributive marker|real name|is called|Zhou Shuren|Lu Xun|is|he|attributive marker|pen name

Der richtige Name von Lu Xun ist Zhou Shuren, Lu Xun ist sein Pseudonym.

El verdadero nombre de Lu Xun era Zhou Shuren, y Lu Xun era su seudónimo.

Il vero nome di Lu Xun è Zhou Shuren, Lu Xun è il suo nome d'arte.

O nome verdadeiro de Lu Xun era Zhou Shuren, e Lu Xun era o seu pseudónimo.

魯迅の本名は周樹人で、魯迅は彼のペンネームです。

Lu Xun's real name is Zhou Shuren, and Lu Xun is his pen name.

鲁迅 生于 1881 年 的 浙江 绍兴 。

|est né|||Zhejiang|Shaoxing

Lu Xun|born in|year|attributive marker|Zhejiang|Shaoxing

Lỗ Tấn|sinh ra|||Chiết Giang|Thượng Hải

|nacque||||

|народився|||Чжэцзян|Шаосін

ルーシュン|生まれた|1881年|の|浙江省|绍兴市

Lu Xun wurde 1881 in Shaoxing, Zhejiang, geboren.

Lu Xun nació en 1881 en Shaoxing, provincia de Zhejiang.

Lu Xun nacque nel 1881 a Shaoxing, Zhejiang.

Lu Xun nasceu em 1881 em Shaoxing, província de Zhejiang.

Лу Сюн народився в 1881 році в китайському місті Шаосін, провінція Чжецзян.

魯迅は1881年に浙江省紹興で生まれました。

Lu Xun was born in 1881 in Shaoxing, Zhejiang.

十九 世纪 末 ,中国 社会 非常 混乱 :西方 帝国 入侵 ,清 政府 渐渐 走向 灭亡 ,人们 希望 实现 民主 。

nineteen|century|end|China|society|very|chaotic|Western|empire|invasion|Qing|government|gradually|move towards|extinction|people|hope|achieve|democracy

Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts war die chinesische Gesellschaft sehr chaotisch: Westliche Reiche fielen ein, die Qing-Regierung starb allmählich aus und die Menschen wollten Demokratie erreichen.

A finales del siglo XIX, la sociedad china estaba sumida en la confusión: los imperios occidentales invadían el país, el gobierno Qing se arruinaba y la gente quería democracia.

À la fin du XIXe siècle, la société chinoise est en plein bouleversement : l'empire occidental a envahi le pays, le gouvernement des Qing est en voie d'extinction et la population aspire à la démocratie.

Alla fine del XIX secolo, la società cinese era molto confusa: le potenze imperiali occidentali invadevano, il governo Qing stava gradualmente andando verso la sua rovina e la gente sperava di realizzare la democrazia.

No final do século XIX, a sociedade chinesa estava a viver um período conturbado: os impérios ocidentais estavam a invadir, o governo Qing estava a cair em ruínas e as pessoas queriam democracia.

В кінці дев'ятнадцятого століття китайське суспільство було дуже хаотичним: західні імперії вторгалися, династія Цін поступово йшла до занепаду, а люди сподівалися на реалізацію демократії.

19世紀末、中国社会は非常に混乱していました:西洋の帝国が侵入し、清政府は徐々に滅亡に向かい、人々は民主主義の実現を望んでいました。

In the late 19th century, Chinese society was very chaotic: Western empires invaded, the Qing government gradually moved towards extinction, and people hoped to achieve democracy.

年轻 的 鲁迅 喜欢 新 事物 ,充满 了 怀疑 精神 。

young|attributive marker|Lu Xun|liked|new|things|full of|past tense marker|doubt|spirit

Der junge Lu Xun mag neue Dinge und ist voller Skepsis.

Al joven Lu Xun le gustaban las cosas nuevas y estaba lleno de escepticismo.

Le jeune Lu Xun aimait la nouveauté et était plein de scepticisme.

Il giovane Lu Xun amava le nuove cose ed era pieno di spirito di dubbio.

Молодий Лу Сюн любив нові речі і був сповнений сумнівів.

若い魯迅は新しい事物を好み、疑いの精神に満ちていました。

Young Lu Xun liked new things and was full of skepticism.

他 父亲 去世 的 时候 ,鲁迅 对 中医 产生 了 严重 的 怀疑 。

he|father|passed away|attributive marker|time|Lu Xun|towards|traditional Chinese medicine|produce|past tense marker|serious|attributive marker|doubt

Als sein Vater starb, hatte Lu Xun ernsthafte Zweifel an der chinesischen Medizin.

A la muerte de su padre, Lu Xun tenía serias dudas sobre la medicina china.

À la mort de son père, Lu Xun a eu de sérieux doutes sur la médecine chinoise.

Quando suo padre morì, Lu Xun sviluppò gravi dubbi sulla medicina tradizionale cinese.

Na altura da morte do seu pai, Lu Xun tinha sérias dúvidas sobre a medicina chinesa.

彼の父親が亡くなったとき、魯迅は中医学に対して深刻な疑念を抱きました。

When his father passed away, Lu Xun developed serious doubts about traditional Chinese medicine.

于是 ,他 去 日本 学习 现代 医学 ,希望 用 自己 的 双手 治病 救人 。

so|he|go|Japan|study|modern|medicine|hope|use|own|attributive marker|hands|treat illness|save people

Also ging er nach Japan, um moderne Medizin zu studieren, in der Hoffnung, mit seinen Händen Krankheiten zu behandeln und Menschen zu retten.

Así que se fue a Japón a estudiar medicina moderna, con la esperanza de utilizar sus manos para curar a los enfermos y salvar vidas.

Il s'est donc rendu au Japon pour étudier la médecine moderne, dans l'espoir d'utiliser ses mains pour soigner les malades et sauver des vies.

Così, andò in Giappone a studiare la medicina moderna, sperando di curare e salvare le persone con le proprie mani.

そこで、彼は日本に行き、現代医学を学び、自分の手で病気を治し人を救うことを望みました。

Therefore, he went to Japan to study modern medicine, hoping to use his own hands to heal and save people.

有 一次 ,他 观看 一部 关于 日 俄 战争 的 纪录片 。

there is|one time|he|watch|one|about|sun|Russia|war|attributive marker|documentary

Einmal sah er einen Dokumentarfilm über den russisch-japanischen Krieg.

Un jour, il a regardé un documentaire sur la guerre russo-japonaise.

C'era una volta che lui guardava un documentario sulla guerra russo-giapponese.

Одного разу він переглядав документальний фільм про Російсько-японську війну.

ある時、彼は日露戦争に関するドキュメンタリーを観ました。

Once, he watched a documentary about the Russo-Japanese War.

中国 人 给 俄国人 做 侦探 ,要 被 日军 枪毙 ,却 有 一群 中国人 在 旁边 观看 。

China|person|to|Russian|to be|detective|to be|by|Japanese army|shot|yet|there are|a group of|Chinese|at|side|watch

Die Chinesen arbeiteten als Späher für die Russen und sollten von den Japanern erschossen werden, aber eine Gruppe von Chinesen beobachtete sie.

Los chinos trabajaban como detectives para los rusos y fueron fusilados por los japoneses mientras un grupo de chinos observaba.

Les Chinois travaillaient comme éclaireurs pour les Russes et allaient être abattus par les Japonais, mais un groupe de Chinois les observait.

Cinesi facevano i detective per i russi, e dovevano essere fucilati dalle truppe giapponesi, ma c'era un gruppo di cinesi a guardare vicino.

Китайці розслідували справу про росіян і мали бути розстріляні японськими військами, але була група китайців, які спостерігали з боку.

中国人がロシア人のためにスパイをして、日軍に銃殺されることになったが、そこには一群の中国人が横で見ていました。

Chinese people were being made detectives for the Russians and were to be executed by the Japanese army, yet there was a group of Chinese people watching nearby.

当时 ,在场 的 日本人 都 欢呼 “万岁 ”。

at that time|present|attributive marker|Japanese people|all|cheer|long live

Zu diesem Zeitpunkt jubelten alle anwesenden Japaner "Hurra!

En ese momento, los japoneses del público gritaron "hurra".

À ce moment-là, tous les Japonais présents ont applaudi "Hourra !

All'epoca, tutte le persone giapponesi presenti applaudivano "Viva!".

Nessa altura, os japoneses na plateia aplaudiram "Hurra".

Тоді японці, які були на місці, радісно кричали «Ура!».

その時、場にいた日本人は皆「万歳」と叫びました。

At that time, the Japanese present were all cheering 'Long live!'

就 在 这个 时候 ,鲁迅 改变 了 自己的 想法 ,决定 用 文学 改变 中国 人的 思想 。

at that time|at|this|time|Lu Xun|change|past tense marker|own|ideas|decide|use|literature|change|China|people's|thoughts

Zu diesem Zeitpunkt änderte Lu Xun seine Meinung und beschloss, die Literatur zu nutzen, um die Chinesen umzustimmen.

Proprio in quel momento, Lu Xun cambiò idea e decise di usare la letteratura per cambiare il pensiero del popolo cinese.

Foi nessa altura que Lu Xun mudou de ideias e decidiu utilizar a literatura para mudar o pensamento do povo chinês.

その瞬間、魯迅は自分の考えを変え、中国人の思想を文学で変えることを決意しました。

It was at this moment that Lu Xun changed his mind and decided to use literature to change the thoughts of the Chinese people.

1918 年 , 鲁迅 发表 了 小说 《 狂人 日记 》 。

Im Jahr 1918 veröffentlichte Lu Xun den Roman Tagebuch eines Verrückten.

En 1918, Lu Xun a publié le roman Journal d'un fou.

Nel 1918, Lu Xun pubblicò il romanzo "Diario di un pazzo".

Em 1918, Lu Xun publicou o seu romance Diário de um Louco.

1918年、魯迅は小説『狂人日記』を発表しました。

In 1918, Lu Xun published the novel 'A Madman's Diary'.

小说 很 短 ,是 十三 篇 日记 。

novel|very|short|is|thirteen|pieces|diary

Der Roman ist sehr kurz und besteht aus dreizehn Tagebucheinträgen.

Le roman est très court et se compose de treize entrées de journal.

Il romanzo è molto breve, composto da tredici diari.

O romance é muito curto, treze entradas de diário.

小説はとても短く、十三篇の日記です。

The novel is very short, consisting of thirteen diary entries.

小说 主角 发现 身边 的 人 都 在 “吃人 ”,他 很 害怕 ,结果 被 人 当成 了 疯子 。

novel|protagonist|discover|around him|attributive marker|people|all|are|eating people|he|very|scared|as a result|by|people|regarded as|past tense marker|madman

Der Protagonist des Romans entdeckt, dass alle um ihn herum "kannibalisch" sind, und ist so verängstigt, dass er für einen Verrückten gehalten wird.

El protagonista de la novela descubre que todo el mundo a su alrededor está "comiendo gente" y se asusta tanto que le tachan de loco.

Le protagoniste du roman découvre que tout le monde autour de lui est "cannibale" et il est tellement effrayé qu'on le prend pour un fou.

Nel romanzo, il protagonista scopre che le persone intorno a lui stanno 'mangiando' gli altri; lui ha molta paura e alla fine è considerato un pazzo.

O protagonista do romance descobre que toda a gente à sua volta está a "comer pessoas" e fica tão assustado que é considerado um louco.

Роман, головний герой виявляє, що люди навколо нього всі "їдять людей", він дуже боїться, в результаті його вважають божевільним.

小説の主人公は、周りの人々が「人を食べている」ことに気づき、彼はとても恐れて、結果的に人々に狂人扱いされます。

The protagonist of the novel discovers that the people around him are all 'eating people', and he is very scared, ultimately being regarded as a madman.

实际 上 ,“吃人 ”的 是 腐朽 的 封建主义 和 人们 的 愚昧 和 无知 ,而 那个 狂人 则 是 一个 善良 的 人 。

actually|on|eat people|attributive marker|is|decayed|attributive marker|feudalism|and|people|attributive marker|ignorance|and|ignorance|but|that|madman|however|is|a|kind|attributive marker|person

In Wirklichkeit sind es der verrottete Feudalismus und die Unwissenheit und Dummheit der Menschen, die "Menschen fressen", während der Wahnsinnige ein guter Mensch ist.

De hecho, fue el feudalismo decadente y la ignorancia y la incultura del pueblo lo que "se comió al hombre".

En fait, c'est le féodalisme pourri, l'ignorance et la stupidité des gens qui "mangent les gens", alors que le fou est un homme bon.

In realtà, 'mangiare' è il feudalesimo decadente e l'ignoranza e la stoltezza delle persone, mentre quel pazzo è una persona gentile.

De facto, foi o feudalismo decadente e a ignorância e desconhecimento do povo que "comeram o homem", mas o louco era um homem bom.

Насправді "їдять людей" це гнилі феодалізм та неосвіченість і невігластво людей, а той божевільний насправді є доброю людиною.

実際には、「人を食べている」のは腐敗した封建主義と人々の愚かさと無知であり、その狂人は善良な人です。

In fact, what is 'eating people' is the decayed feudalism and people's ignorance and foolishness, while that madman is a kind-hearted person.

《 狂人 日记 》 使用 容易 理解 的 白话文 , 而 不是 文言文 , 也 就是 古代 的 书面语 。

Das Tagebuch eines Verrückten ist in leicht verständlicher Volkssprache geschrieben, nicht in der Literatursprache, der alten Schriftsprache.

El Diario de un loco está escrito en lengua vernácula de fácil comprensión, no en lengua literaria, que es la antigua lengua escrita.

Le Journal d'un fou est écrit en langue vernaculaire facilement compréhensible, et non en langue littéraire, qui est la langue écrite ancienne.

'Diario di un pazzo' usa un linguaggio colloquiale facile da comprendere, piuttosto che il linguaggio classico, che è la lingua scritta dell'antichità.

O Diário de um Louco é escrito em vernáculo de fácil compreensão, não em linguagem literária, que é a linguagem escrita antiga.

«Деньник богевільного» написаний зрозумілою розмовною мовою, а не класичною, тобто давньою письмовою мовою.

『狂人日記』は理解しやすい口語体で書かれており、文語体、つまり古代の書き言葉ではありません。

'A Madman's Diary' uses easily understandable vernacular instead of classical Chinese, which is the written language of ancient times.

紧接着 ,鲁迅 又 写 了 小说 《 孔乙己 》 。

immediately after|Lu Xun|again|wrote|past tense marker|novel|Kong Yiji

Unmittelbar danach schrieb LU Xun den Roman Kong Yi Ji.

Lu Xun escribió entonces su novela Kong Yiji.

Immédiatement après, LU Xun écrit le roman Kong Yi Ji.

Subito dopo, Lu Xun scrisse il romanzo "Kong Yiji".

Lu Xun escreveu então o seu romance Kong Yiji.

その後、魯迅は小説『孔乙己』を書きました。

Immediately after, Lu Xun wrote the novel 'Kong Yiji'.

孔乙己 是 一个 只 知道 读书 的 人 ,他 的 目标 就是 通过 考试 当官 ,但 他 失败 了 。

Kong Yiji|is|a|only|know|reading|attributive marker|person|he|attributive marker|goal|is|through|exams|become an official|but|he|failed|past tense marker

Kong Yiji ist eine Person, die nur Bücher lesen kann. Sein Ziel ist es, die Prüfung zu bestehen und Beamter zu werden, aber er hat versagt.

Confucio era un hombre que sólo sabía estudiar y su objetivo era aprobar un examen para convertirse en funcionario, pero fracasó.

Kong Yijie est un homme qui ne sait que lire, et son objectif est de devenir fonctionnaire en passant l'examen, mais il échoue.

Kong Yiji è una persona che sa solo leggere, il suo obiettivo è passare gli esami per diventare un funzionario, ma fallisce.

Confúcio era um homem que só sabia estudar e o seu objetivo era passar num exame para se tornar funcionário, mas falhou.

孔乙己は、ただ本を読むことしか知らない人です。彼の目標は、試験に合格して官僚になることですが、彼は失敗しました。

Kong Yiji is a person who only knows how to read books. His goal is to pass the exams and become an official, but he failed.

他 读 的 书 只能 用来 考试 ,却 无法 给 他 带来 食物 。

he|read|attributive marker|book|can only|be used for|exam|but|cannot|give|him|bring|food

Die Bücher, die er liest, können nur für Prüfungen verwendet werden, aber sie können ihm kein Essen bringen.

Los libros que leía sólo le servían para los exámenes, pero no le daban de comer.

Les livres qu'il lit ne peuvent être utilisés que pour les examens, mais ils ne peuvent pas lui apporter de nourriture.

I libri che legge può usarli solo per gli esami, ma non possono dargli da mangiare.

Os livros que lia só podiam ser utilizados para os exames, mas não lhe davam comida.

彼が読んでいる本は試験のためだけに使われ、彼に食べ物をもたらすことはできません。

The books he reads can only be used for exams, but they cannot provide him with food.

他 没有 了 尊严 ,人们 嘲笑 他 。

he|does not have|emphasis marker|dignity|people|mock|him

Er verlor seine Würde und die Leute lachten über ihn.

Il n'a aucune dignité et les gens se moquent de lui.

Lui non ha più dignità, le persone lo deridono.

彼は尊厳を失い、人々は彼を嘲笑します。

He has lost his dignity, and people mock him.

他 还 去 偷 书 ,结果 被 人 打 断 了 腿 。

he|still|go|steal|books|as a result|by|people|hit|break|past tense marker|leg

Er wollte das Buch stehlen, war aber kaputt.

También fue a robar un libro y le rompieron una pierna.

Il est également allé voler des livres, a été battu et a eu les jambes cassées.

Lui andò a rubare un libro, e alla fine gli romptero una gamba.

Também foi roubar um livro e partiu uma perna.

彼は本を盗みに行き、その結果、足を折られました。

He even went to steal books, and as a result, he had his leg broken by someone.

鲁迅 通过 这个 可怜 的人 讽刺 了 当时 的 社会 。

Lu Xun|through|this|pitiful|person|satirize|past tense marker|at that time|attributive marker|society

Lu Xun verspottete die damalige Gesellschaft durch diesen armen Mann.

A través de este pobre hombre, Lu Xun satiriza la sociedad de su tiempo.

Lu Xun a fait la satire de la société de l'époque à travers ce pauvre homme.

Lu Xun ha usato questa povera persona per fare satira della società dell'epoca.

Através deste pobre homem, Lu Xun satiriza a sociedade do seu tempo.

魯迅はこの可哀想な人を通じて、当時の社会を皮肉っています。

Lu Xun satirizes the society of that time through this pitiful person.

几年 后 ,鲁迅 又 发表 了 小说 《 阿Q 正传 》 。

how many years|later|Lu Xun|again|publish|past tense marker|novel|Ah Q|The True Story

Einige Jahre später veröffentlichte Lu Xun den Roman Die wahre Geschichte von Ah Q.

Unos años más tarde, Lu Xun publicó otra novela, A Q Zhengzhuan.

Dopo alcuni anni, Lu Xun pubblicò nuovamente il romanzo 'La vera storia di Ah Q'.

Alguns anos mais tarde, Lu Xun publicou outro romance, A Q Zhengzhuan.

数年後、魯迅は小説『阿Q正伝』を発表しました。

A few years later, Lu Xun published the novel "The True Story of Ah Q."

阿Q 很 穷 ,也 不 知道 自己 的 名字 怎么 写 。

Ah Q|very|poor|also|not|know|oneself|attributive marker|name|how|write

Ah Q ist sehr arm und weiß nicht, wie er seinen Namen schreiben soll.

Q era muy pobre y no sabía escribir su nombre.

Ah Q était très pauvre et ne savait pas écrire son nom.

Ah Q è molto povero e non sa nemmeno come si scrive il suo nome.

Q era muito pobre e não sabia escrever o seu nome.

阿Qはとても貧しく、自分の名前の書き方も知りません。

Ah Q is very poor and doesn't even know how to write his own name.

他 很 可怜 ,却 不 努力 。

he|very|pitiful|but|not|work hard

Er ist sehr erbärmlich, aber er arbeitet nicht hart.

Es pobre, pero no lo intenta.

Il est pathétique, mais il n'essaie pas.

È molto miserabile, ma non si impegna.

Ele é pobre, mas não se esforça.

彼はとても可哀想ですが、努力しません。

He is very pitiful, yet he does not make an effort.

为了 求生 ,他 发明 了 “精神 胜利 法 ”:当 他 遭到 不幸 的时候 ,就 在 精神 上 麻痹 自己 ,什么 都 不 去 想 。

in order to|survive|he|invented|past tense marker|mental|victory|method|when|he|encountered|misfortune|time|then|at|mental|on|numb|oneself|anything|at all|not|go to|think

Um zu überleben, erfand er die "Spiritual Victory Method": Als er unglücklich war, lähmte er sich mental und dachte nichts.

Para sobrevivir, inventó el "método del triunfo espiritual": cuando era golpeado por la desgracia, se paralizaba mentalmente y no pensaba en otra cosa.

Pour survivre, il invente la "méthode de la victoire spirituelle" : lorsqu'il est frappé par un malheur, il se paralyse mentalement et ne pense à rien d'autre.

Per sopravvivere, ha inventato la 'legge della vittoria spirituale': quando si trovava in difficoltà, si anestetizzava mentalmente, non pensava a nulla.

Para sobreviver, inventou o "método do triunfo espiritual": quando era atingido pelo infortúnio, paralisava-se mentalmente e não pensava noutra coisa.

生き延びるために、彼は「精神的勝利法」を発明しました:不幸に遭ったとき、精神的に自分を麻痺させ、何も考えないようにします。

In order to survive, he invented the "spiritual victory method": when he encounters misfortune, he numbs himself mentally and thinks of nothing.

鲁迅 写 《 阿Q 正传 》 ,讽刺 了 中国人 的 性格 问题 。

Lu Xun|wrote|Ah Q|The True Story|satirized|past tense marker|Chinese people|attributive marker|character|problem

Lu Xun schrieb "Die wahre Geschichte von Ah Q", das das chinesische Schriftzeichen verspottete.

Lu Xun a écrit "La véritable histoire d'Ah Q" pour faire la satire des problèmes de caractère des Chinois.

Lu Xun ha scritto 'La vera storia di Ah Q', satirizzando i problemi caratteriali degli cinesi.

Lu Xun escreveu "A Verdadeira História de Ah Q", uma sátira sobre o carácter do povo chinês.

魯迅は『阿Q正伝』を書き、中国人の性格の問題を風刺しました。

Lu Xun wrote "The True Story of Ah Q" to satirize the character issues of the Chinese people.

鲁迅 的 小说 收集 在 《 呐喊 》 和 《 彷徨 》 两本 书 里面 。

Lu Xun|attributive marker|novels|collected|in|Call to Arms|and|Wandering|two|books|inside

Lu Xuns Romane sind in zwei Büchern zusammengefasst, "Scream" und "Wandering".

Las novelas de Lu Xun se recogen en dos libros, Na Yao y Wandering.

Les romans de Lu Xun sont rassemblés dans deux livres, Scream et Wandering.

I romanzi di Lu Xun sono raccolti nei due libri 'Chiamata' e 'Indeterminatezza'.

Os romances de Lu Xun estão reunidos em dois livros, Na Yao e Wandering.

魯迅の小説は『呐喊』と『彷徨』の二冊に収められています。

Lu Xun's novels are collected in the two books "A Call to Arms" and "Wandering."

后来 ,鲁迅 写 了 很多 散文 和 杂文 ,更加 直接 地 批评 当时 中国 的 各种 问题 。

later|Lu Xun|wrote|past tense marker|many|essays|and|miscellaneous writings|even more|directly|adverbial marker|criticize|at that time|China|attributive marker|various|problems

Später schrieb Lu Xun viele Essays und Essays und kritisierte verschiedene Probleme in China zu dieser Zeit direkter.

Más tarde, Lu Xun escribió muchos ensayos y artículos diversos para criticar más directamente los diversos problemas de la China de la época.

In seguito, Lu Xun scrisse molti saggi e articoli, criticando più direttamente i vari problemi della Cina dell'epoca.

Mais tarde, Lu Xun escreveu muitos ensaios e artigos diversos para criticar mais diretamente os vários problemas da China da época.

その後、魯迅は多くの散文や雑文を書き、当時の中国の様々な問題をより直接的に批判しました。

Later, Lu Xun wrote many essays and critiques, more directly criticizing various issues in China at that time.

他 的 著名 散文 集 有 《 朝花夕拾 》 和 《 野草 》 ,杂文 集 有 《 二心集 》 和 《 华盖集 》 。

he|attributive marker|famous|prose|collection|has|Morning Flowers Picked at Dusk|and|Weeds|essays|collection|has|Two Minds Collection|and|Umbrella Collection

Zu seinen berühmten Aufsatzsammlungen gehören "Gesammelte Blumen am Abend" und "Wild Grass", und zu den Aufsatzsammlungen gehören "Essence Collection of Two Hearts" und "Collection of Huagai".

Entre sus famosas colecciones de ensayos figuran Las flores de la mañana y Las hierbas silvestres, y entre sus ensayos misceláneos, La colección de los dos corazones y La colección Huagai.

Le sue famose raccolte di saggi includono 'La raccolta di fiori del mattino e dell'ombra della sera' e 'Erba selvatica', mentre le sue raccolte di articoli comprendono 'Raccolta di cuori divisi' e 'Raccolta di coperture floreali'.

As suas famosas colecções de ensaios incluem The Flowers in the Morning e The Wild Grasses, e os seus ensaios diversos incluem The Two Hearts Collection e The Huagai Collection.

彼の著名な散文集には『朝花夕拾』と『野草』があり、雑文集には『二心集』と『華蓋集』があります。

His famous essay collections include "Dawn Blossoms Plucked at Dusk" and "Wild Grass," while his critique collections include "The Two Hearts Collection" and "The Umbrella Collection."

鲁迅 对 中国 古代 文学 做 了 一些 研究 。

|||||||recherches|

Lu Xun|on|China|ancient|literature|do|past tense marker|some|research

|||văn học cổ đại||||nghiên cứu|

|||letteratura antica||||ricerche|

|||давня література||||дослідження|

ルーシュン|に対して|中国|古代|文学|行った|過去形を示す助詞|一部の|研究

Lu Xun forschte über alte chinesische Literatur.

Lu Xun ha investigado sobre la literatura china antigua.

Lu Xun ha condotto alcune ricerche sulla letteratura cinese antica.

Lu Xun fez algumas pesquisas sobre a literatura chinesa antiga.

魯迅は中国の古代文学についていくつかの研究を行いました。

Lu Xun conducted some research on ancient Chinese literature.

除此之外 ,鲁迅 也 翻译 了 很多 外国 的 文学 作品 ,把 各种 新 思想 介绍 到 中国 。

apart from this|Lu Xun|also|translated|past tense marker|many|foreign|attributive marker|literature|works|to|various|new|ideas|introduced|to|China

Darüber hinaus übersetzte Lu Xun auch viele ausländische literarische Werke und brachte verschiedene neue Ideen nach China.

Además, Lu Xun también tradujo muchas obras literarias extranjeras e introdujo nuevas ideas en China.

Oltre a ciò, Lu Xun ha tradotto molte opere letterarie straniere, introducendo vari nuovi pensieri in Cina.

Além disso, Lu Xun também traduziu muitas obras literárias estrangeiras e introduziu novas ideias na China.

それに加えて、魯迅は多くの外国の文学作品を翻訳し、様々な新しい思想を中国に紹介しました。

In addition, Lu Xun also translated many foreign literary works, introducing various new ideas to China.

鲁迅 相信 民主 ,支持 学生 运动 ,也 因此 得罪 了 当时 的 政府 。

Lu Xun|believe|democracy|support|student|movement|also|therefore|offend|past tense marker|at that time|attributive marker|government

Lu Xun glaubte an Demokratie und unterstützte die Studentenbewegung, die die damalige Regierung beleidigte.

Lu Xun creía en la democracia y apoyó el movimiento estudiantil, ofendiendo así al gobierno de la época.

LU Xun croyait en la démocratie et soutenait le mouvement étudiant, ce qui a heurté le gouvernement de l'époque.

Lu Xun credeva nella democrazia e supportava i movimenti studenteschi, e per questo si è messo contro il governo dell'epoca.

Lu Xun acreditava na democracia e apoiou o movimento estudantil, ofendendo assim o governo da época.

Лу Сюн вірив у демократію, підтримував студентський рух і через це образив тодішній уряд.

魯迅は民主を信じ、学生運動を支持したため、当時の政府に敵を作った。

Lu Xun believed in democracy, supported student movements, and thus offended the government at that time.

他 曾经 在 北京 的 政府 工作 ,后来 逃 到 南方 。

he|once|in|Beijing|attributive marker|government|work|later|escape|to|south

Er arbeitete in der Regierung von Peking und floh später in den Süden.

Ha lavorato in passato per il governo a Pechino, poi è fuggito nel sud.

Trabalhou para o governo em Pequim antes de fugir para o sul.

Він працював у федеральному уряді в Пекіні, а потім втік на південь.

彼はかつて北京の政府で働いていたが、その後南方に逃げた。

He once worked in the government in Beijing, and later escaped to the south.

他 在 各地 的 大学 给 学生 上课 、演讲 ,影响 了 很多 人 ,特别 是 年轻人 。

he|at|various places|attributive marker|university|to|students|teach classes|give speeches|influence|past tense marker|many|people|especially|is|young people

Er hielt Vorlesungen und Vorlesungen für Studenten an Universitäten überall und betraf viele Menschen, insbesondere junge Menschen.

Il a donné des conférences et des discours aux étudiants des universités du monde entier et a influencé de nombreuses personnes, en particulier des jeunes.

Lui insegna agli studenti e fa conferenze nelle università di varie parti, influenzando molte persone, specialmente i giovani.

Deu palestras e falou a estudantes em universidades de todo o mundo, influenciando muitas pessoas, especialmente os jovens.

Він проводив уроки та лекції для студентів у університетах по всій країні, впливаючи на багатьох людей, особливо на молодь.

彼は各地の大学で学生に授業を行い、講演をし、多くの人々、特に若者に影響を与えた。

He taught and gave lectures to students at universities across the country, influencing many people, especially young people.

直到 今天 ,人们 依然 认为 鲁迅 是 中国 最 重要 的 作家 、思想家 和 革命家 。

until|today|people|still|believe|Lu Xun|is|China|most|important|attributive marker|writer|thinker|and|revolutionary

Bis heute gilt Lu Xun als Chinas wichtigster Schriftsteller, Denker und Revolutionär.

Aujourd'hui encore, LU Xun est considéré comme l'écrivain, le penseur et le révolutionnaire le plus important de Chine.

Fino ad oggi, le persone continuano a considerare Lu Xun come il più importante scrittore, pensatore e rivoluzionario della Cina.

До сьогодні люди все ще вважають Лю Сюня найважливішим письменником, мислителем і революціонером Китаю.

今日に至るまで、人々は魯迅が中国で最も重要な作家、思想家、革命家であると考えている。

Even today, people still consider Lu Xun to be the most important writer, thinker, and revolutionary in China.

听说 最近 教科书 里 鲁迅 的 文章 被 删除 了 ,这 引起 了 人们 的 讨论 。

heard that|recently|textbook|in|Lu Xun|attributive marker|articles|passive marker|deleted|past tense marker|this|caused|past tense marker|people|attributive marker|discussion

Ich habe gehört, dass der Artikel von Lu Xun im Lehrbuch kürzlich gelöscht wurde, was die Diskussion der Leute anregte.

He oído que los artículos de Lu Xun han sido retirados recientemente de los libros de texto, lo que ha suscitado un gran debate.

J'ai entendu dire que les articles de Lu Xun ont récemment été supprimés des manuels scolaires, ce qui a suscité de nombreuses discussions.

Ho sentito dire che recentemente gli articoli di Lu Xun sono stati rimossi dai libri di testo, il che ha suscitato discussioni tra le persone.

Ouvi dizer que os artigos de Lu Xun foram recentemente retirados dos manuais escolares, o que suscitou muita discussão.

最近、教科書から魯迅の文章が削除されたと聞き、これが人々の議論を引き起こした。

It is said that recently Lu Xun's articles have been removed from textbooks, which has sparked discussions among people.

支持者 说 ,因为 鲁迅 已经 不能 代表 这个 时代 了 ;反对者 说 ,因为 鲁迅 笔下 的 人 全部 复活 了 。

supporter|said|because|Lu Xun|already|cannot|represent|this|era|emphasis marker|opponent|said|because|Lu Xun|under the pen|attributive marker|people|all|resurrect|emphasis marker

Unterstützer sagen, weil Lu Xun diese Ära nicht mehr repräsentieren kann, sagen Gegner, weil alle von Lu Xun beschriebenen Menschen auferstanden sind.

Los partidarios dicen que Lu Xun ya no representa su época; los detractores, que todas las personas sobre las que escribió han vuelto a la vida.

Les partisans disent que c'est parce que LU Xun ne peut plus représenter cette époque ; les opposants disent que c'est parce que tous les personnages des écrits de LU Xun sont revenus à la vie.

I sostenitori dicono che Lu Xun non può più rappresentare questo tempo; gli oppositori dicono che tutti i personaggi descritti da Lu Xun sono tornati in vita.

Os defensores dizem que Lu Xun já não representa o seu tempo; os opositores dizem que todas as pessoas sobre as quais escreveu voltaram à vida.

支持者は言う、なぜなら魯迅はもうこの時代を代表できないからだ;反対者は言う、なぜなら魯迅の筆の下の人々はすべて復活したからだ。

Supporters say that Lu Xun can no longer represent this era; opponents say that all the characters in Lu Xun's writings have come back to life.

SENT_CWT:9r5R65gX=5.19 PAR_TRANS:gpt-4o-mini=4.11 SENT_CWT:AsVK4RNK=6.71 PAR_TRANS:gpt-4o-mini=2.54 SENT_CWT:AsVK4RNK=27.57 PAR_TRANS:gpt-4o-mini=2.78

ja:9r5R65gX en:AsVK4RNK en:AsVK4RNK

openai.2025-01-22

ai_request(all=50 err=0.00%) translation(all=41 err=0.00%) cwt(all=527 err=4.17%)