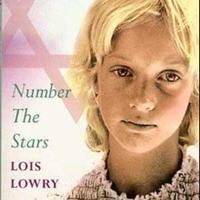

Number the Stars by Lois Lowry Ch 3

3 Where Is Mrs. Hirsch? The days of September passed, one after the other, much the same. Annemarie and Ellen walked to school together, and home again, always now taking the longer way, avoiding the tall soldier and his partner. Kirsti dawdled just behind them or scampered ahead, never out of their sight.

The two mothers still had their “coffee” together in the afternoons. They began to knit mittens as the days grew slightly shorter and the first leaves began to fall from the trees, because another winter was coming. Everyone remembered the last one. There was no fuel now for the homes and apartments in Copenhagen, and the winter nights were terribly cold.

Like the other families in their building, the Johansens had opened the old chimney and installed a little stove to use for heat when they could find coal to burn. Mama used it too, sometimes, for cooking, because electricity was rationed now. At night they used candles for light. Sometimes Ellen's father, a teacher, complained in frustration because he couldn't see in the dim light to correct his students' papers. “Soon we will have to add another blanket to your bed,” Mama said one morning as she and Annemarie tidied the bedroom.

“Kirsti and I are lucky to have each other for warmth in the winter,” Annemarie said. “Poor Ellen, to have no sisters.” “She will have to snuggle in with her mama and papa when it gets cold,” Mama said, smiling. “I remember when Kirsti slept between you and Papa. She was supposed to stay in her crib, but in the middle of the night she would climb out and get in with you,” Annemarie said, smoothing the pillows on the bed. Then she hesitated and glanced at her mother, fearful that she had said the wrong thing, the thing that would bring the pained look to her mother's face. The days when little Kirsti slept in Mama and Papa's room were the days when Lise and Annemarie shared this bed. But Mama was laughing quietly. “I remember, too,” she said. “Sometimes she wet the bed in the middle of the night!” “I did not!” Kirsti said haughtily from the bedroom doorway. “I never, ever did that!” Mama, still laughing, knelt and kissed Kirsti on the cheek. “Time to leave for school, girls,” she said. She began to button Kirsti's jacket. “Oh, dear,” she said, suddenly. “Look. This button has broken right in half. Annemarie, take Kirsti with you, after school, to the little shop where Mrs. Hirsch sells thread and buttons. See if you can buy just one, to match the others on her jacket. I'll give you some kroner—it shouldn't cost very much.” But after school, when the girls stopped at the shop, which had been there as long as Annemarie could remember, they found it closed. There was a new padlock on the door, and a sign. But the sign was in German. They couldn't read the words. “I wonder if Mrs. Hirsch is sick,” Annemarie said as they walked away.

“I saw her Saturday,” Ellen said. “She was with her husband and their son. They all looked just fine. Or at least the parents looked just fine—the son always looks like a horror.” She giggled.

Annemarie made a face. The Hirsch family lived in the neighborhood, so they had seen the boy, Samuel, often. He was a tall teenager with thick glasses, stooped shoulders, and unruly hair. He rode a bicycle to school, leaning forward and squinting, wrinkling his nose to nudge his glasses into place. His bicycle had wooden wheels, now that rubber tires weren't available, and it creaked and clattered on the street. “I think the Hirsches all went on a vacation to the seashore,” Kirsti announced.

“And I suppose they took a big basket of pink-frosted cupcakes with them,” Annemarie said sarcastically to her sister.

“Yes, I suppose they did,” Kirsti replied.

Annemarie and Ellen exchanged looks that meant: Kirsti is so dumb. No one in Copenhagen had taken a vacation at the seashore since the war began. There were no pink-frosted cupcakes; there hadn't been for months. Still, Annemarie thought, looking back at the shop before they turned the corner, where was Mrs. Hirsch? The Hirsch family had gone somewhere. Why else would they close the shop?

Mama was troubled when she heard the news. “Are you sure?” she asked several times.

“We can find another button someplace,” Annemarie reassured her. “Or we can take one from the bottom of the jacket and move it up. It won't show very much.” But it didn't seem to be the jacket that worried Mama. “Are you sure the sign was in German?” she asked. “Maybe you didn't look carefully.” “Mama, it had a swastika on it.” Her mother turned away with a distracted look. “Annemarie, watch your sister for a few moments. And begin to peel the potatoes for dinner. I'll be right back.” “Where are you going?” Annemarie asked as her mother started for the door. “I want to talk to Mrs. Rosen.” Puzzled, Annemarie watched her mother leave the apartment. She went to the kitchen and opened the door to the cupboard where the potatoes were kept. Every night, now, it seemed, they had potatoes for dinner. And very little else.

Annemarie was almost asleep when there was a light knock on the bedroom door. Candlelight appeared as the door opened, and her mother stepped in.

“Are you asleep, Annemarie?” “No. Why? Is something wrong?” “Nothing's wrong. But I'd like you to get up and come out to the living room. Peter's here. Papa and I want to talk to you.” Annemarie jumped out of bed, and Kirsti grunted in her sleep. Peter! She hadn't seen him in a long time. There was something frightening about his being here at night. Copenhagen had a curfew, and no citizens were allowed out after eight o'clock. It was very dangerous, she knew, for Peter to visit at this time. But she was delighted that he was here. Though his visits were always hurried—they almost seemed secret, somehow, in a way she couldn't quite put her finger on—still, it was a treat to see Peter. It brought back memories of happier times. And her parents loved Peter, too. They said he was like a son.

Barefoot, she ran to the living room and into Peter's arms. He grinned, kissed her cheek, and ruffled her long hair.

“You've grown taller since I saw you last,” he told her. “You're all legs!” Annemarie laughed. “I won the girls' footrace last Friday at school,” she told him proudly. “Where have you been? We've missed you!” “My work takes me all over,” Peter explained. “Look, I brought you something. One for Kirsti, too.” He reached into his pocket and handed her two seashells.

Annemarie put the smaller one on the table to save it for her sister. She held the other in her hands, turning it in the light, looking at the ridged, pearly surface. It was so like Peter, to bring just the right gift.

“For your mama and papa, I brought something more practical. Two bottles of beer!” Mama and Papa smiled and raised their glasses. Papa took a sip and wiped the foam from his upper lip. Then his face became more serious.

“Annemarie,” he said, “Peter tells us that the Germans have issued orders closing many stores run by Jews.” “Jews?” Annemarie repeated, “Is Mrs. Hirsch Jewish? Is that why the button shop is closed? Why have they done that?” Peter leaned forward. “It is their way of tormenting. For some reason, they want to torment Jewish people. It has happened in the other countries. They have taken their time here—have let us relax a little. But now it seems to be starting.” “But why the button shop? What harm is a button shop? Mrs. Hirsch is such a nice lady. Even Samuel—he's a dope, but he would never harm anyone. How could he—he can't even see, with his thick glasses!” Then Annemarie thought of something else. “If they can't sell their buttons, how will they earn a living?” “Friends will take care of them,” Mama said gently. “That's what friends do.” Annemarie nodded. Mama was right, of course. Friends and neighbors would go to the home of the Hirsch family, would take them fish and potatoes and bread and herbs for making tea. Maybe Peter would even take them a beer. They would be comfortable until their shop was allowed to open again.

Then, suddenly, she sat upright, her eyes wide. “Mama!” she said. “Papa! The Rosens are Jewish, too!” Her parents nodded, their faces serious and drawn. “I talked to Sophy Rosen this afternoon, after you told me about the button shop,” Mama said. “She knows what is happening. But she doesn't think that it will affect them.” Annemarie thought, and understood. She relaxed. “Mr. Rosen doesn't have a shop. He's a teacher. They can't close a whole school!” She looked at Peter with the question in her eyes. “Can they?” “I think the Rosens will be all right,” he said. “But you keep an eye on your friend Ellen. And stay away from the soldiers. Your mother told me about what happened on Østerbrogade.” Annemarie shrugged. She had almost forgotten the incident. “It was nothing. They were only bored and looking for someone to talk to, I think.” She turned to her father. “Papa, do you remember what you heard the boy say to the soldier? That all of Denmark would be the king's bodyguard?” Her father smiled. “I have never forgotten it,” he said.

“Well,” Annemarie said slowly, “now I think that all of Denmark must be bodyguard for the Jews, as well.” “So we shall be,” Papa replied. Peter stood. “I must go,” he said. “And you, Longlegs, it is way past your bedtime now.” He hugged Annemarie again.

Later, once more in her bed beside the warm cocoon of her sister, Annemarie remembered how her father had said, three years before, that he would die to protect the king. That her mother would, too. And Annemarie, seven years old, had announced proudly that she also would.

Now she was ten, with long legs and no more silly dreams of pink-frosted cupcakes. And now she—and all the Danes—were to be bodyguard for Ellen, and Ellen's parents, and all of Denmark's Jews. Would she die to protect them? Truly? Annemarie was honest enough to admit, there in the darkness, to herself, that she wasn't sure. For a moment she felt frightened. But she pulled the blanket up higher around her neck and relaxed. It was all imaginary, anyway—not real. It was only in the fairy tales that people were called upon to be so brave, to die for one another. Not in real-life Denmark. Oh, there were the soldiers; that was true. And the courageous Resistance leaders, who sometimes lost their lives; that was true, too.

But ordinary people like the Rosens and the Johansens? Annemarie admitted to herself, snuggling there in the quiet dark, that she was glad to be an ordinary person who would never be called upon for courage.