CHAPTER XXV. SERMONS IN CHALK.

Now, see here, Marion Wilbur, wake up and give me your attention. I want to make a speech; I've caught the infection. It's queer in a place where there is so much speech-making done that I can't have a chance to express my views." "I'm all attention," Marion answered, turning on her pillow, and giving Eurie a sleepy stare. "What has moved you to be eloquent? Give me the subject." "The subject is the reflex influence of preaching! It may have different effects on different natures. Its effect on mine has been marked enough. I'm thoroughly surfeited. I don't want to hear another sermon while I am here, and I don't mean to. They are all sermons. The subject may be scientific, literary or artistic, and it amounts to the same thing; they contrive to row around to the same spot from whatever point they start. Now, I came here for fun, and I'm being literally cheated out of it. So the application of my remark is, I've learned since I have been here always to have an application to everything, and this time it is that I won't go any more. I've studied the programme carefully, and I have selected just what I am going to do. That Mrs. Knox has a reception this morning. I've heard about her before; she is awfully in earnest, and awfully good. Oh, I haven't the least doubt of it; but, you see, I don't want to be good, nor to have such an uncomfortable amount of goodness about me." "She is said to be one of the most successful Sabbath-school teachers here; and I heard a gentleman say last night that her primary class was a regular training school for young ladies in Christian work. You know she has ever so many teachers under her." "I can't help that. I am not one of them, I am thankful to say. What do I care whether she is successful or not? That won't help me any. I know all about her. They say the young ladies in her classes are invariably converted before they have been under her influence long. So if you want to be converted you have only to go to Elmira and join her class; but as for me, I am not in the mood for that experience yet, and I am not going near her." "What are you going to do then?" "Just what I please! That is what I came for. Just think of the absurdity of we four girls rushing to meeting at the rate we have been doing for the last week. What do you suppose the people at home would think of us? Why, I didn't expect to hear any of their sermons when I came. I as good as promised Flossy that I would frolic about with her all the time, and now the absurd little dunce acts as if she were under a wager to be on the ground every time the bell rings! I've declared off. I can tell you to an item just what I am going to hear. There is a performance to come off this afternoon some time that I shall be ready for. I loitered behind the King tent last night, and heard him say so. That Frank Beard is going to give his chalk talk—caricatures: that I shall hear, and especially see . It will be hard work to poke a sermon into that. I guess that is to be this afternoon; it is to be some time soon, anyway, and I shall watch for it. Then there is to be another extra. Mrs. Miller is going to read a story. I can give you the title of it. I didn't sit on that horrid stump in the dark listening to Dr. Vincent for nothing. It is to be 'Three Blind Mice.' Now it stands to reason that a story with such a title will not be very far above my intellectual capacity, and it can't very well develop into a sermon, or close with a prayer-meeting. Then I'm going to the concert by the Tennesseeans;' their jargon won't hurt me; and, of course, I shall attend the President's reception. I must have a stare at him—and that is every solitary meeting I am going to attend. I've heard the last preaching that I mean to for some time." Now this was what Eurie Mitchell said . Let me tell you a little bit about what she thought . She was by no means so indifferent, nor so bored as she would have Marion understand. She was by no means in the state of mind that Ruth had been, or that Marion was. No doubts as to the general truth of all the vital doctrines of Christianity had ever troubled her. She accepted without question the belief of the so-called Christian World. Neither was she bewildered as to what constituted Christian life. No vague notion that to unite herself with some church would let her into the charmed circle had ever befogged her brain.

On the contrary, she knew better than many a Christian does just what the Christian profession involved, and just how narrow a path ought to be walked by those professing to follow Christ. In proportion to the keenness of her sarcasm over blundering, stumbling Christians, had her eyes been open to what they ought to be.

There was just this the matter with Eurie. She knew so well what religious professions involved that she wanted to make none. She hated the thought of self-abnegation, of bridling her eager tongue, of going only where her enlightened conscience said a Christian should go, of looking out for and calling after others to go with her. She wished deliberately to ignore it all. Not forever, she would have been shocked at the thought. Some time she meant to give intense heed to these things, and then indeed the church should see what a Christian could be! But not now.

There were a hundred things laid down in her programme for the coming winter that she knew perfectly well were not the things to do or say, provided she were a Christian, and she deliberately wished to avoid the fear of becoming one. Just here she was afraid of the influence of Chautauqua.

How was it possible to attend these meetings, to listen to these daily, hourly addresses, teeming either directly or indirectly with the same thought, personal consecration, without feeling herself drawn within the circle? She would not be drawn. This was her deliberate conclusion, therefore her determination.

It was almost well for her that she could not realize on what fearfully dangerous ground she was treading! I wonder if those over whom the Lord says, "Let them alone," are ever conscious at the time that the order has gone forth, and that they are to feel their consciences pressing home this matter no more? "Well," said Marion, after turning this resolution over in her mind for a few minutes, "I dare say you will lose a good many things worth hearing; but I have nothing to do with that—only I want you to go with me up to hear Mrs. Knox this morning. I've got to go, for I promised especially to report her for the teachers at home, and it is stupid to go alone. She won't preach, and she won't bore you, and I want you to help me remember items." So, much against her will, Eurie was coaxed into this departure from her programme, and came back from the meeting in intense disgust.

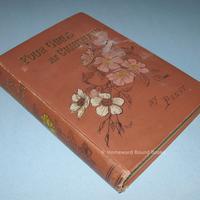

"Talk about her not preaching," she said, venting her annoyance on Marion while she energetically brushed her hair. "Every fold of her dress preached a sermon! She makes me ache all over, she is so powerfully in earnest; and didn't she hint what angels of goodness those girls of hers were—those teachers! I'd like to know how they could be anything else but good with such an example at hand. Just think, Marion, of having the brains that that woman has, and the energy and tact and the skill of a general, and then forcing it into a Sunday-school class room for the teaching of a hundred little dots that have just tumbled out of their cradles!" "Well, if she teaches them to tumble out on the right side so that they will come up grand men and women, what then? Isn't that an ambition worthy of her?" "Stuff and nonsense! Don't you go to preaching. I shall go and drown myself in the lake if I hear any more of it, and then one worthless person will be out of the way. But don't you dare to ask me to go and hear that woman again! I won't give up my plans in life for hers, and she needn't hint it to me. And, Marion Wilbur, I am not going to listen to another man or woman who has the least chance to fire words right at me—now mark my words." Full of this determination she carried it out during the afternoon, until the hour for Frank Beard's caricatures; then, secure from fear of a sermon, she came gayly down and considered herself fortunate to secure a seat directly in front of the stand and in full view of the blackboard. If you have never seen Frank Beard make pictures you know nothing about what a good time she had. They were such funny pictures! —just a few strokes of the magic crayon and the character described would seem to start into life before you, and you would feel that you could almost know what thoughts were passing in the heart of the creature made of chalk. Eurie looked, and listened, and laughed. The old deacon who thought the Sunday-school was being glorified too much had his exact counterpart among her acquaintances, so far as his looks were concerned. The three troublesome Sunday-school scholars fairly convulsed her by their life-like appearance. There was the little scamp of a boy who was revealed by the dozen to any one who took a walk down town toward the close of the day; the argumentative old man, with his nose pointing out a flaw in your reasoning or on the keen scent for a mistake; and the pert fourteen-year-old girl whose very nose, as it slightly turned upward, showed that she knew more than all the logicians and theologians in the world.

This entertainment was exactly in Eurie's line. If there was anything in the world that she was an adept at it was looking up weak points in the characters of other people; and when the silly girl with but two ideas—one of them bows and the other beaux—lived and breathed before her on the blackboard her delight reached its climax.

"She is the very picture of Nettie Arnold!" she whispered to Marion. "When I go home I mean to tell her that her photograph was displayed at Chautauqua. She is just vain enough to believe it!" Still the fun went on. Just a few bold, rapid strokes, and some caricature breathed before them, so real that the character was guessed before the explanation was given, and the ground rang with continued and overpowering roars of laughter.

Into the midst of this entertainment came Dr. Vincent, his face aglow with the exertion of hearty laughter, every feature of it expressive of his hearty appreciation of this hour of recreation and yet every feature alive and alert with a higher and more enduring feeling.

"Frank," he said, laying a friendly hand on the artist's arm, "our time is almost up. Give us the symbol of the teacher's work." There was an instant of rapid motion, a few skillful lines, and it needed no word of explanation to recognize the great family Bible. "Now the symbol of the teacher's hope," and on one page of the open Bible there flashed an anchor. "Now the symbol of his reward," and lo, there rose up before them the solid wall, built brick by brick. Dr. Vincent's voice was almost husky with feeling, so suddenly had the play of his emotions changed, as he said: "Now we want the foundation." How did Frank Beard do it with a dull colored crayon and a half-dozen movements of his skillful arm? How can I tell, except that God has given to the arm wondrous skill; but there appeared before that astonished multitude a foundation as of granite, and there rose from it, as if suddenly hewed out before them, a clean-cut solid shaft of gray, imperishable granite. One more dash of the wondrous crayon and the shaft was done—a solid cross!

Prof. Sherwin was sitting, for want of a better position, on the floor of the stand. It was the only available space. He had been looking and enjoying as only men like Prof. Sherwin can; and now, as he watched the outgrowth of this wonderful cross, as the last stroke was given that made it complete, and a sound like a subdued shout of joy and triumph murmured through the crowd, moved as by a sudden mighty impulse that he could not control, his splendid voice burst forth in the glorious words:

"Rock of Ages, cleft for me, Let me hide myself in Thee." And that great multitude took it up and rolled the tribute of praise down those resounding aisles until people bowed themselves, and some of them wept softly in the very excess of their joy and thanksgiving. It was all so sudden, so unexpected; yet it was so surely the key-note to the Chautauqua heart, and fitted in so aptly with their professions and intentions. They could play for a few minutes—none could do it with better hearts or more utter enjoyment than these same splendid leaders—but how surely their hearts turned back to the main thought, the main work, the main hope, in life and in death.

As for Eurie, she will not be likely to forget that sermon. It almost overpowered her. There came over her such a sudden and eager longing to understand the depths from whence such feeling sprung, to rest her feet on the same foundation, that for the moment her heart gave a great bound and said: "It is worth all the self-denial and all the change of life and plans which it would involve. I almost think I want that rather than anything else." That miserable "almost!" I wonder how many souls it has shipwrecked? The old story. If Eurie had been familiar with her Bible it would surely have reminded her of the foolish listener who said, while he trembled under the truth, " Almost thou persuadest me to be a Christian." Shall I tell you what came in, just then and there, to influence her decision? It was such a miserable little thing—nothing more than the remembrance of certain private parties that were a standing institution among "their set" at home, to meet fortnightly in each other's parlors for a social dance. Not a ball! oh, no, not at all. These young ladies did not attend balls , unless occasionally a charity ball, when a very select party was made up. Simply quiet evenings among special friends, where the special amusement was dancing.

"Dear me!" you say, "I am a Christian, and I don't see anything wrong in dancing . Why, I dance at private parties very often. What was there in that thought that needed to influence her?" Oh, well, we are not arguing, you know. This is simply a record of matters and things as they occurred at Chautauqua. It can hardly be said to be a story, except as records of real lives of course make stories.

But Eurie was not a Christian, you see; and however foolish it may have been in her she had picked out dancing as one of the amusements not fitting to a Christian profession. It is a queer fact, for the cause of which I do not pretend to account, but if you are curious, and will investigate this subject, you will find that four fifths of the people in this world who are not Christiana have tacitly agreed among themselves that dancing is not an amusement that seems entirely suited to church-members. If you want to get at the reason for this strange prejudice, question some of them. Meantime the fact exists that Eurie felt herself utterly unwilling to give up the leadership of those fortnightly parties, and that the trivial question actually came in then and there, while she stood looking at that picture of the cross; and in proportion as her sudden conviction of desire lost itself in this whirl of intended amusement did her disgust arise at the thought that she had been actually betrayed into listening to another sermon!