30. Across the Blue Waters

"Without freedom, what wert thou, Greece? Without thee, Greece, what were the world?" —MÜLLER.

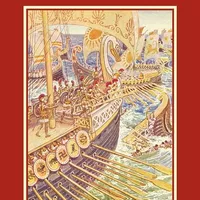

Just across the blue Mediterranean from Sicily, lay the flourishing colony of Carthage, belonging to the Phœnicians. Now there was great rivalry between these two people, for each owned large possessions along the shores of the Great Sea, and the men of Carthage were known to covet the rich colony of Sicily. It lay but fifty miles across that tideless blue sea, an easy enough voyage for the clever Phœnicians. At last they saw their chance of attacking the Greeks there.

Xerxes, the great King of Persia, was attacking the mother country, Phœnician sailors were manning her ships; was not this the time for the sailors of younger Phœnicia—even the men of Carthage—to sail across and take the younger Greece—even Sicily?

The men of Carthage began to prepare under their commander, Hamilcar. When all was ready they set sail with three thousand ships and an enormous number of men. They had men from the island of Sardinia, from the island of Corsica, and men from Spain; but on the way over, they encountered a terrific storm and a number of ships and horses were lost.

Hamilcar landed at Palermo, at the western end of the three-cornered island.

"The war is over," he murmured as he stepped on shore, so sure did he feel that he would win. Here he gave his army a rest and then marched on Himera. There he dragged his ships on shore and made a deep ditch to protect them.

A long and terrible battle was fought, in which the men of Carthage were hopelessly defeated, and the Carthaginians went home and told a grand story of the death of their commander.

"All day long," they said, "Hamilcar stood apart from the fight, like Moses of old. All day—for the battle raged from sunrise to sunset—he threw burnt-offerings into a great fire, according to the belief of his forefathers. Towards evening the news reached him, that his army was defeated. The moment for the greatest sacrifice of all had come. And Hamilcar threw himself into the burning fire as the most costly gift of all." The rest of the story is equally tragic. Another storm overtook the returning fleet, and one little boat alone carried back to Carthage the dismal news that its army, fleet, and commander had perished.

The battle of Himera was fought on the same day as the battle of Salamis, and on both occasions the Greeks were victorious. They had fought bravely for their freedom, they had thrown off the yoke of Persia and the yoke of Carthage.

We must see now what use Greece made of her liberty, and how she taught the world that commerce and trade were not the only ends in view, that ambition in itself was paltry, and how she created that beauty and art, which have influenced nation upon nation, and which play so large a part in the civilisation of to-day.